7.3 Our assessment Tā mātau arotake

7.3.1 Vaccination saved lives and protected Aotearoa New Zealand from the worst impacts of COVID-19

In 2024, the journal Vaccine published a study modelling the health impacts attributable to COVID-19 vaccination in Aotearoa New Zealand between January 2022 and June 2023. It estimated that during this period vaccines saved 6,650 lives and prevented 45,100 hospitalisations.31

The study also showed the benefits of vaccination were not enjoyed equitably, with Māori having lower vaccination rates and correspondingly higher rates of preventable hospitalisations and deaths.32 We discuss vaccine equity in more detail in section 7.3.2.

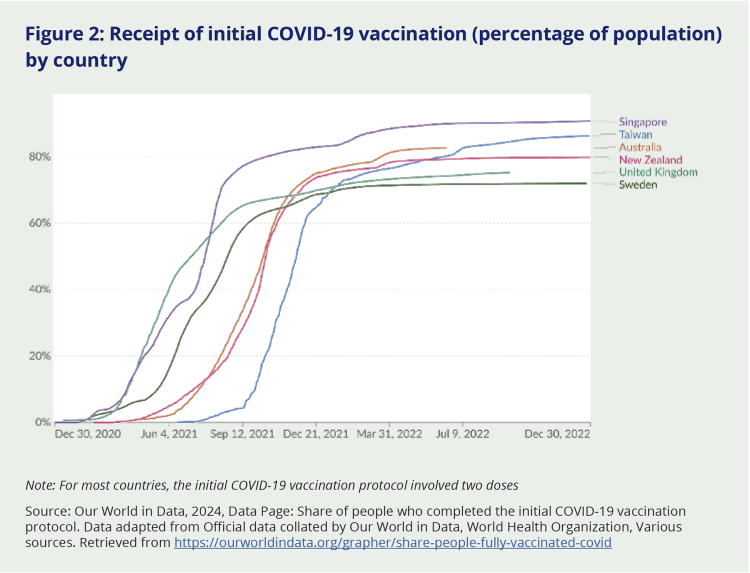

International comparisons of vaccine benefits and coverage are difficult, given significant differences in the pandemic’s global trajectory and national responses. In terms of vaccine uptake, Figure 2 shows that by late 2021, a higher proportion of people in Aotearoa New Zealand were fully vaccinated than in some comparable countries that began their vaccine rollouts earlier:

Figure 2: Receipt of initial COVID-19 vaccination (percentage of population) by country

Note: For most countries, the initial COVID-19 vaccination protocol involved two doses

Source: Our World in Data, 2024, Data Page: Share of people who completed the initial COVID-19 vaccination protocol. Data adapted from Official data collated by Our World in Data, World Health Organization, Various sources. Retrieved from https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/share-people-fully-vaccinated-covid

The Vaccine modelling study and others emphasise that vaccination complemented other elements of Aotearoa New Zealand’s pandemic response; together, they ‘delivered one of the lowest pandemic mortality rates of any country in the world’.33 A group of public health experts writing in the New Zealand Medical Journal also highlighted the interdependence of the elimination strategy (which successfully delayed widespread COVID-19 transmission for nearly two years) and the vaccination strategy (which delivered high population immunity before the virus became established).34 They pointed to the lasting protective effect of these combined strategies: even though New Zealand later experienced high rates of infection and reinfection, especially during Omicron waves, levels of excess mortality were exceptionally low, particularly compared with other countries.35

Such findings speak to the significant role vaccination played in protecting New Zealand from the high burden of illness and death many other countries faced during the pandemic. The expectation that vaccines would significantly reduce the threat posed by COVID-19 and help bring the pandemic under control underpinned the initial response. The country’s comparatively low rates of COVID-19 illness and death support the decision to pursue elimination until effective vaccines could be developed and administered to the majority of the population.

7.3.1.1 Thanks to an enormous nationwide effort, the vaccine rollout succeeded in achieving high levels of coverage

The rollout of the COVID-19 vaccine was the largest and most challenging immunisation programme ever undertaken in Aotearoa New Zealand. Early estimates showed that for every adult in the country to receive the recommended two doses, 8 million doses had to be administered (by comparison, 1.5 million doses are typically delivered each year as part of the annual influenza vaccination programme).

The rollout achieved the Government’s’ central objective – ensuring high population immunity before exposure to COVID-19 became widespread. This outcome is testament to the enormous effort of officials, health providers (including primary care providers, pharmacies and Māori and Pacific organisations), communities, local leaders and individuals. Many members of the public who made submissions to our Inquiry acknowledged these efforts. They were grateful that vaccines were free of charge and easily accessible to many, and they commended the rollout’s effectiveness and accessibility.

“Having the mobile vaccination centres was great as it meant we didn’t have to travel 45 minutes to the nearest larger town to access this. This was particularly useful with small children as it was less of a logistics mission to accomplish.”

“I found the vaccine roll out to be smooth and I was glad for the prioritisation of vulnerable groups.”

“The vaccination programme prevented people dying and protected those that had health conditions.”

According to stakeholder evidence, crucial factors that enabled the rollout included government investment in improving relevant information systems and instances of cross-agency collaboration – such as the Ministry of Health bringing in the New Zealand Defence Force logistical expertise to ensure vaccines were kept at the right temperature during transportation. And we heard again and again that Māori and Pacific health providers were particularly effective in the vaccine rollout, especially with their own populations (although these providers were often frustrated by what they saw as missed opportunities to mobilise earlier and maximise their effectiveness – see section 7.3.2).

"Pasifika providers and communities got involved and started to organise drive-in events. The Tongans vaccinated 1,000 people in one day. This set the tone… [and] started to turn things around. They created a fun atmosphere to draw people in. Finally, officials started to trust them to organise and provided resources… Had we moved earlier, trusted and engaged the communities and leaders, we would have had a different response. We got there in the end, but why did it take so long?”

The Auditor-General acknowledged the pressure the Government was under to deliver the vaccination programme as quickly as possible in his review of rollout preparations released in May 2021. Public expectations for a speedy rollout were high at the time; it was well-understood that the sooner most of the population was vaccinated, the quicker Aotearoa New Zealand would move on from lockdowns, reopen its borders and begin its economic recovery. This created considerable pressure, the Auditor-General noted: ‘Other countries are moving ahead with their vaccination programmes. In our view, it is important for the Government to maintain public trust and confidence by ensuring that New Zealand does not fall significantly behind’.36

In practice, Aotearoa New Zealand’s immunisation programme was very effective in quickly delivering high levels of vaccine coverage at an overall population level. As Figure 2 shows, New Zealand’s vaccine rollout followed a similar timeline to that in Australia, with both countries starting their programmes somewhat later than countries such as the United Kingdom, the United States and Singapore. But vaccine uptake was both quicker and more sustained in New Zealand and Australia. New Zealand achieved 80 percent vaccination with two doses on 26 November 2021,x ahead of both the United Kingdom and the United States.

Where the vaccine rollout was less successful was in delivering equitable coverage across different population groups. Consistent with the concerns noted earlier, there were delays in ensuring access to vaccination for some higher-risk groups – including Māori and Pacific peoples.

7.3.1.2 A highly centralised approach to the vaccine rollout meant opportunities were missed to ensure the vaccine reached everyone equally quickly

Despite the evident effort that went into the vaccine rollout, and the high rates of coverage it had achieved by late 2021, opportunities were missed to ensure vaccine access and uptake were optimised for high-risk groups, including Māori and Pacific peoples, at the same time as for the rest of the population. Decision-makers were aware before the rollout began of the potential for unequal vaccine coverage (an issue we discuss further in section 7.3.2).37 While equity of coverage was a prominent consideration in policy advice, findings from the Auditor-General’s report – supported by accounts from community providers – suggest that delivering on the immunisation programme’s stated commitments to equity would have required earlier involvement of Māori and Pacific providers and a greater willingness to relax central control in favour of more community-led provision.38 We heard from senior figures both inside and outside of government that more could have been done to ensure earlier involvement and better resourcing of local health providers (particularly Māori and Pacific organisations), which might have improved early vaccine uptake in some high-risk groups. At the same time, we are conscious that those leading the vaccine rollout were under pressure to deliver a large and complex programme as quickly as possible, and were managing many practical constraints that made it difficult to involve a broad range of providers and locations in the initial stages of the vaccine rollout.39

The vaccination rollout was initially designed with a high degree of central control. This reflected the need to quickly deliver a large and complex programme while carefully managing initially limited vaccine supplies. The Ministry of Health had an enormous task in designing the vaccination programme, setting up relevant information support systems (such as the bespoke COVID-19 Immunisation Register) and operationalising key aspects of the vaccine rollout (such as approving and training COVID-19 vaccinators and distributing doses to vaccination sites).40 District health boards were responsible for the vaccination sites; they were required to use Ministry guidelines, clinical standards and information systems, but had ‘some discretion over how they administer the vaccines to best meet the needs of their communities’.41 The Ministry clearly took its responsibility tosteward scarce resources seriously, as is appropriate for the agency leading a public health response of this scale.

Nevertheless, the highly centralised approach to the initial vaccine rollout – including where and how vaccines would be provided, what training vaccinators needed and who should be prioritised for vaccination – frustrated many local leaders and health providers. They told us of burdensome administrative hurdles that had to be overcome before vaccines would be delivered. And they described missed opportunities to meet local needs or overcome access barriers (unless they bent the rules, which some reported doing).

“Pasifika leaders were advocating for Pacific-led vaccination centres and bespoke training of Pacific vaccinators, ‘but the system just could not respond’.”

“In this pandemic, we kept telling DHBs and the Ministry of Health … You have to prepare to be mobile. To use trucks for mobile vaccinations. It took too long to get approval, the pandemic was over. It took the length of the pandemic to get it right.”

While there was a clear and justifiable desire to ‘support the “best use” of COVID-19 vaccines’, as the Immunisation Strategy required, the Government’s highly centralised approach unintentionally compromised the second part of that strategic objective: ‘upholding and honouring te Tiriti of Waitangi obligations and promoting equity’. This highlights the challenge of balancing distinct and sometimes competing goals in a complex operational environment. As we describe below, it had serious and damaging consequences for already vulnerable groups and may have also delayed Aotearoa New Zealand’s recovery overall. From the start of the pandemic, Government messaging had presented vaccination as the pathway out of, and justification for, the elimination strategy and the restrictions it involved. A stronger and earlier focus on achieving equity in the vaccine rollout – including through targeted measures to increase Māori and Pacific vaccination rates – would have seen the country reach its immunisation target earlier, allowing lockdowns and other stringent restrictions to be relaxed sooner.

At the same time, centralising the rollout made it easier to ensure the safe and efficient delivery of a new vaccine that was in short supply. Initial requirements meant the vaccine had to be stored and transported at very low temperatures (-70°C), and vaccination at large, central sites was thought to reduce the risk of wastage. Bespoke training of vaccinators was potentially more expensive and time-consuming, but it reflected the importance of administering the vaccine safely. Vaccinators were required who were not just technically competent, but could give people accurate and appropriate information. This was critical, as highlighted by the rare but devastating cases where things went wrong and people suffered as a result.42 Guidance from the World Health Organization’s Strategic Advisory Group of Experts on Immunisation notes that myocarditis (inflammation of the heart) is a ‘rare adverse event’ that can occur following administration of mRNA COVID-19 vaccines, including the Pfizer vaccine.43

See discussion of international assessments of vaccine effectiveness and safety in section 7.2.2.

7.3.1.3 Hesitancy and misinformation challenged vaccine uptake

The rollout was challenged by growing vaccine hesitancy – that is, when people delayed or declined getting vaccinated because they lacked confidence, motivation and/or ease of access.44 This became a major global challenge in the COVID-19 pandemic as vaccine messaging was complicated by the rapid spread of misinformation and disinformation.45 (Misinformation and disinformation are also discussed in Chapters 2 and 8.) We heard from several stakeholders that lower vaccine uptake among younger people was at least partly driven by their greater exposure to misinformation by the time they were eligible to be vaccinated. This was a particular issue for Māori and Pacific communities given their younger age structure and historically lower trust of mainstream health providers.46 As one senior Māori health official told us, ‘We gave too much of a run-in for misinformation to get out there and take hold … We missed an opportunity to vaccinate our people early, and as a result we saw resistance come in’.

Efforts to boost vaccine uptake included the use of vaccine incentives (such as food or petrol vouchers) by health providers and the introduction of vaccine requirements (such as passes) by the Government (discussed in Chapter 8). Other countries used similar ‘carrot and stick’ approaches to maximise COVID-19 vaccine coverage, with positive impacts on uptake.

We heard mixed views on the use of vaccine incentives. While generally viewed as effective in the short term, some people felt they were unfair or inappropriate, and we heard anecdotal accounts of people receiving expensive items (such as laptops) or delaying or repeating vaccination in order to receive incentives. But others argued that incentives addressed underlying needs in these communities: in the words of one Māori leader, ‘Some people called it a bribe; we call it manaakitanga’.

The Inquiry notes that the use of direct incentives raises complex ethical challenges. Material ‘rewards’ for vaccination can create perverse incentives – meaning people may delay vaccination (waiting for incentives to be offered before presenting) or seek vaccination when they are not eligible. We also heard from health providers who were concerned that use of incentives for COVID-19 vaccination might create expectations that would impact future vaccination programmes, leading to lower vaccination coverage unless people were offered ‘rewards’ for vaccine uptake. The Inquiry notes that maximal effort should be put into reducing barriers to vaccine access in order to reduce the need for direct incentives.

We heard from many people about the importance of engaging with community leaders as ‘trusted voices’ who could encourage and reassure people in relation to vaccination. The Ministry of Health’s communications team identified this as an important part of their strategy to counter misinformation and disinformation about the vaccine. They also noted that the introduction of vaccine mandates (discussed in Chapter 8) made it more difficult to maintain a positive framing around vaccination. This point was echoed in engagements with other health stakeholders, who felt the use of mandates had a negative effect on trust in many communities and even reduced some people’s willingness to be vaccinated.

The issue of vaccine hesitancy is linked with – and complicated by – the fact that vaccines (like most medicines) are not entirely without risk. Where a vaccine has been used for many years, these risks are usually well understood. But COVID-19 vaccines were very new at the point they were rolled out, and – while evidence on their safety was available from clinical trials – it was not possible to fully understand the risk of very rare adverse effects (such as might occur with only one in a million doses) until the vaccine had been administered to much larger groups of people. As this occurred, it became apparent that mRNA COVID-19 vaccines such as the Pfizer vaccine are linked with a small but potentially serious risk of myocarditis, particularly in young men (see section 7.2.2).

The evolving nature of this evidence is likely to have been a contributing factor in vaccine hesitancy, as it may have created the impression that experts and officials were withholding information from members of the public. In practice, both Medsafe and the Ministry of Health issued several communications (from June 2021 onwards) advising vaccinators and the public about the potential risk of myocarditis following vaccination with the Pfizer vaccine.47 While the frequency and changing content of these updates reflected a desire to communicate the most current evidence, it was challenging for people to keep on top of and process this information. The Health and Disability Commissioner noted the desirability of having stronger mechanisms for providing clear and consistent advice on vaccine risks – a recommendation our Inquiry supports.48

We heard mixed views on the use of vaccine incentives. While generally viewed as effective in the short term, some people felt they were unfair or inappropriate.

7.3.2 Despite an in-principle focus on equity of coverage, vaccination uptake and access were lower for Māori and Pacific peoples than for other groups

As noted earlier, the existence of wide disparities in health and wellbeing was well-known before COVID-19 reached Aotearoa New Zealand. Māori, Pacific peoples, disabled people, people living in poverty, some rural communities and people experiencing mental illness were all known to have poorer health outcomes than the general population. The health and disability system therefore understood that ‘existing health inequities would result in the pandemic having a disproportionate impact on these people without equity-focused response measures’.

There were compelling public health reasons for putting equity at the centre of the response (beyond the pragmatic argument that individuals are better protected in a pandemic if all members of society are protected). Memories of the 1918 influenza pandemic’s devastating and disproportionate impact on Māori remained front of mind for many communities, officials and Members of Parliament. Prioritising equity was also consistent with the Crown’s te Tiriti o Waitangi responsibilities. A commitment to equity was thus prominent in many aspects of the pandemic response, including the decision to adopt an elimination approach and the immunisation strategy – the purpose of which, as we have already noted, was to support the ‘best use’ of vaccines ‘while upholding and honouring te Tiriti o Waitangi obligations and promoting equity’.49 The COVID-19 Health and Disability System Response Plan warned of the ‘potential for equity failure with the exacerbation of existing inequities and the creation of new inequities’ and devoted several pages to the need to embed the equity principle in pandemic decision-making.50

The evidence we have reviewed suggests the Government was committed in principle to equity and upholding te Tiriti. In designing the vaccination rollout, the Ministry of Health paid particular attention to supporting access for older people, for Māori and Pacific people, and for people with disabilities. These groups were highlighted in advice on the vaccine sequencing framework, and district health boards were encouraged to work closely with Māori, Pacific and disability healthcare providers on plans for the vaccination rollout.51 Keeping Māori health equity at the heart of the vaccination rollout was also the aim of the COVID-19 Māori Vaccine and Immunisation Plan, which the Ministry of Health released in March 2021.52 It set out how the vaccination rollout would give effect to the Crown’s te Tiriti obligations to ensure equitable health outcomes, including by working closely with iwi and Māori representatives. The plan emphasised the important role of Māori health providers, who had proved critical to the success of the COVID-19 response so far. The recent influenza vaccination programme had shown that more equitable outcomes were possible when Māori providers delivered services to Māori in a Māori way. The Ministry had therefore ring-fenced funding for Māori vaccination providers and for a service to ‘support and empower whānau’ through vaccine information and access.53

Particularly after the Delta outbreak, the Ministry of Health, district health boards and providers expanded options for accessing COVID-19 vaccinations, including via general practices and pharmacies (as agreed by Cabinet on 23 August 2021). As part of this expansion, the Ministry of Health contracted Māori and other community providers, seeking to implement what it described as a ‘whānau-centred approach’ in Māori communities ‘so whānau could be vaccinated in groups, for multiple things at the same time where appropriate and in a range of locations to suit [them], including at home and on marae’. Similarly, from August 2021 vaccinations were offered to Pacific communities in places such as churches and community centres. Pacific peoples had been disproportionately impacted by COVID-19 from the start, accounting for 75 percent of active cases linked to community transmissions by August 2020. The Ministry also set up mobile outreach and pop-up sites to meet the needs of remote rural communities.

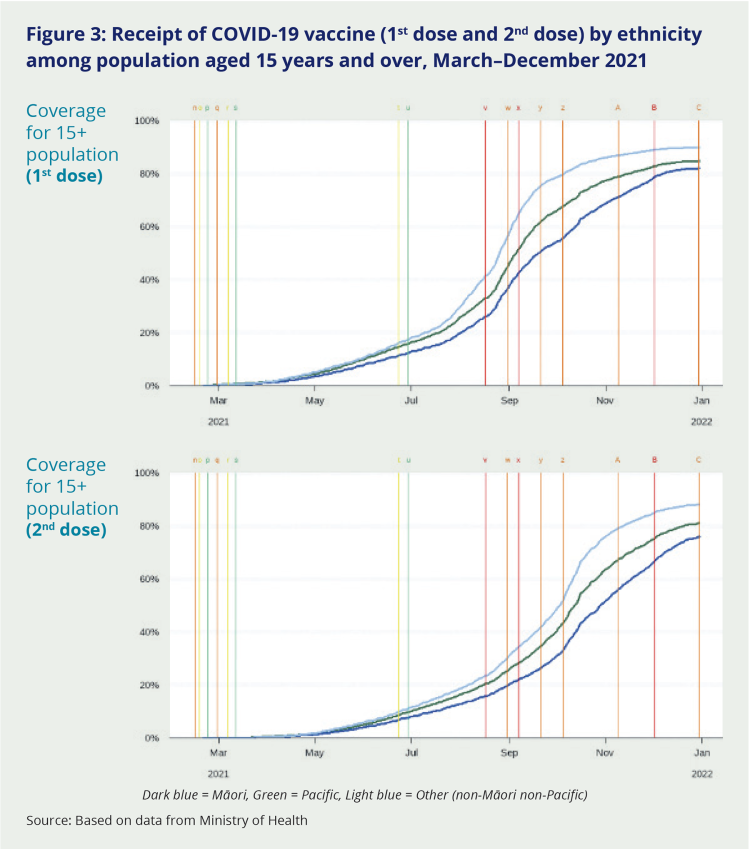

While evidence from our engagements showed such initiatives were effective in reaching relevant communities, it appears these efforts occurred too late in the rollout to deliver more equitable vaccination rates across the population. As shown in Figure 3, by August 2021, vaccination among Māori and Pacific populations was already substantially lower than for people who were neither Māori or Pacific, and the gap was never closed. It is likely that in the absence of efforts to expand reach to these communities, the disparities in vaccine uptake would have been even worse. It is important to recognise the significant effort invested in improving vaccine reach, and the benefits gained in terms of vaccination uptake in vulnerable communities. But it is equally important to recognise that even greater equity gains could have been achieved by starting the outreach to Māori, Pacific peoples and disadvantaged and rural communities earlier.xi

Figure 3: Receipt of COVID-19 vaccine (1st dose and 2nd dose) by ethnicity among population aged 15 years and over, March–December 2021

Dark blue = Māori, Green = Pacific, Light blue = Other (non-Māori non-Pacific)

Source: Based on data from Ministry of Health

The 2024 modelling study published in Vaccine offered further insights into how their lower vaccination coverage affected Māori mortality. It estimated that if Māori vaccination rates had been the same as non-Māori, between 11 and 26 percent of the 292 Māori COVID-19 deaths recorded between January 2022 and June 2023 could have been prevented.54 The authors noted that other factors – such as poor access to healthcare, lower quality housing and higher rates of co-morbidities – also contributed to the higher Māori hospitalisation and mortality rates.

That up to a quarter of Māori deaths could have been avoided if vaccination rates had been equal is a stark demonstration of the meaning of health equity and what happens in its absence.

This disparity – and likely inequity – is particularly salient given that concerns about equity were raised with decision-makers even before vaccination had started. It also reinforces that the initial approach to the rollout did not facilitate sufficient involvement of Māori, Pacific and other community providers. The Auditor-General’s review of preparations found that, as early as February 2021, officials had expressed concern that ‘equitable access to the vaccine was not being properly incorporated into the immunisation programme’ and that it was unclear where responsibility and accountability for equity lay.55 The Auditor-General noted that changes to the programme’s structure and staffing had since improved matters. Even so, he found evidence of ongoing delays in funding and vaccine supplies for Māori and Pacific providers, noting that much still needed to be done to ensure equity:56

“District health boards are still working out how they will organise aspects of the vaccine roll-out in their communities. Some are well-positioned, but others have a lot of work to do. … Although a lot of thought has been given to ensure that everyone (Māori and Pasifika communities in particular) can access the vaccine in a way that meets their social, linguistic, and cultural needs, it is not yet clear whether this will be fully achieved. At the time this audit was completed, many in the wider health and disability sector were still not clear about what their role will be or when they will know.”

The Auditor-General’s report recommended that the Ministry of Health keep working with district health boards and Māori, Pacific and disability healthcare providers ‘to make sure equity considerations are fully embedded in delivery plans’.57

Ministry of Health officials had sought to place equity at the centre of the COVID-19 immunisation programme. In March 2021, the COVID-19 Vaccine Technical Advisory Group advocated prioritising Māori and Pacific peoples (and some other vulnerable groups) for vaccination at a younger age than the rest of the population since they were at greater risk of serious illness.58 This advice was included in the Ministry of Health’s briefing to Cabinet, which recommended including Māori and Pacific peoples over 50 years of age in Group 3 of the sequencing framework.59 (The proposed approach was referred to as an ‘age adjustment’ since it sought to ‘adjust’ the Group 3xii age-threshold for Māori and Pacific peoples in recognition of their higher risk of severe outcomes from COVID-19 infection.)

Cabinet did not follow officials’ advice to use a younger age threshold for Māori and Pacific peoples in the vaccine rollout. Instead, they sought to ensure equitable vaccine access via other mechanisms – including promoting a ‘whānau-centred’ approach to the vaccine rollout, enabling household members to be vaccinated alongside older Māori and Pacific people and prioritising of people with co-morbidities (noting co-morbidities are more common, by age, among Māori and Pacific peoples). District health boards were also given a degree of flexibility in how they decided to prioritise the vaccine rollout in their area.60

The intention behind Cabinet’s decision was to ensure Māori and Pacific peoples were appropriately prioritised in the vaccine rollout. Unfortunately, this intention was not consistently reflected in the implementation of the complex immunisation programme. As discussed previously, pressure to deliver a fast vaccine rollout while managing scarce vaccine supply initially (and understandably) resulted in a centralised approach. Vaccination centres were strongly focused on careful stewardship of vaccine doses – an approach that was sometimes in tension with equity considerations. As a result, involvement of Māori and Pacific providers was limited until August 2021. This created unintended barriers to vaccine access – and hence an inequity – for many Māori and Pacific communities.

Cabinet’s decision not to follow officials’ advice in relation to the vaccine sequencing framework was heavily criticised in the Waitangi Tribunal’s priority report Haumaru, released at the end of 2021. The New Zealand Māori Council, supported by a several Māori health providers, lodged a claim with the Tribunal asserting that the Crown’s vaccination strategy and plan (and the COVID-19 Protection Framework, introduced later in the pandemic) were inconsistent with te Tiriti. The Tribunal upheld the claim on several counts. It found that Cabinet’s decision to reject advice from officials to adopt an age adjustment for Māori in the vaccine rollout breached the treaty principles of active protection and equity. It also found the Crown breached the principle of partnership and the guarantee of te tino rangatiratanga by failing to jointly design the vaccine sequencing framework with Māori, while its inconsistent engagement with Māori more generally was another breach of partnership.61 Haumaru criticised delays in provision of funding to Māori health providers, which it said had contributed to lower vaccine uptake among Māori, while poor communication and mixed messaging had undermined the potential for a ‘whānau-centred’ vaccine rollout. These actions and others occurred despite advice that Māori health leaders and iwi leaders were giving the Government, the Tribunal said.62

The Government undertook several measures in response to the Haumaru report, including providing an additional $140 million for Māori and Pacific providers to support the health response to Omicron and targeted support to improve vaccination uptake for Māori.63 It also committed to improved monitoring of Māori health outcomes, including through the establishment of the Māori Health Authority | Te Aka Whai Ora.

Since Haumaru was released, other equity-related reviews of the Government’s pandemic response have highlighted inequities in the vaccination strategy and rollout. One review (commissioned by the Ministry of Health and based on interviews with mostly Māori and Pacific whānau, stakeholders and service providers) concluded that equity had been ‘actively discarded as an objective’ in the vaccination strategy and that the Ministry needed to do better in any future pandemic response.64

It is clear that the Government understood the importance of protecting Māori interestsin the vaccination strategy and rollout: the many references to its te Tiriti obligations in guiding documents speak to this. Unfortunately, this clear intention to protect Māori failed to translate into equitable implementation of the COVID-19 vaccine rollout. This implementation risk was flagged by the Auditor-General when the rollout was still in its early stages and later confirmed by the Waitangi Tribunal.65

We note that the Ministry of Health sought to respond to the Waitangi Tribunal’s findings by working with Māori providers to improve vaccine access for Māori and by strengthening its ability to monitor vaccine uptake by ethnicity. It is not our role to identify breaches of te Tiriti. However, the general thrust of the Waitangi Tribunal’s findings are consistent with evidence we reviewed from many sources, showing the significant benefits that were achieved when the Government did undertake genuine te Tiriti-based engagement with iwi and Māori; when it trusted them to lead, organise and deliver vaccination in ways that responded to local needs and barriers and resourced this accordingly. In our view, when responding to a future pandemic, the Government must not only document its responsibility to ensure equitable outcomes for Māori in policy statements, but also give effect to this responsibility in implementation. This comment is not intended to dismiss the significant efforts that were made to ensure the vaccine rollout reached everyone, but to note the opportunity to do better in future by trusting and resourcing community expertise. We return to this in the lessons for the future and recommendations set out later in our report.

The vaccination rollout also fell short of delivering equitable outcomes for Pacific peoples. Like Māori, they too were affected by Cabinet’s decision not to adjust the vaccination age threshold for those ethnic groups at greatest risk of severe outcomes from COVID-19 infection. Pacific health providers experienced delays in receiving funding and vaccine supplies, and some told us they were often blocked when they tried to lead or organise vaccination in ways they knew would work for their communities. We do not have quantitative evidence of the likely impact on Pacific COVID-19 mortality (unlike the impact of lower vaccine uptake on Māori mortality, which has been modelled). But as Pacific peoples suffered the highest mortality risk of all ethnic groups (see Figure 3), it is only logical that inequities in vaccine access and uptake contributed to this outcome.

It is a human right to refuse medical treatment such as vaccination, and not all people will be willing or feel able to be vaccinated. There will therefore be variation in vaccine uptake across the population, due in part to differences in people’s preferences and beliefs. This variation is not regarded as an inequality if it reflects genuine choice based on sound information. However, vaccine coverage is also impacted by factors other than personal or whānau choice – including geographical barriers, lack of cultural alignment between providers and those receiving vaccines, and historical breaches of trust. It is the Inquiry’s view that lower vaccine coverage among Māori and Pacific peoples is primarily due to these broader factors. For example, while lower coverage in Māori partly reflected higher vaccine hesitancy in Māori communities, this was itself driven by delays in bringing Māori providers into the rollout, greater exposure to misinformation and disinformation, and higher mistrust of government.66 The Inquiry therefore regards lower vaccine coverage in Māori and Pacific peoples as an inequality.

Spotlight: Māori and Pacific vaccine providers | Ngā kaiwhakarato rongoā āraimate Māori me Ngā Uri Moutere

“When you left us to deliver the services ourselves, we did an exceptional job.”

Pacific community healthcare provider

“We were getting reports about vaccination rates and seeing there were problems with Māori uptake... In the end, we just … gave the money to Iwi and community groups, and that worked.”

Cabinet Minister

The effectiveness of Māori and Pacific health providers in the vaccine rollout – supported by strong national and community leadership – was a recurrent theme in our Inquiry.67

Government agencies acknowledged the value these providers brought. In October 2021, Te Puni Kōkiri told ministers that Māori providers, iwi groups and organisations ‘have deep connections and networks into their communities that can reach whānau often on the margins of government responses. Importantly, these providers, groups and organisations are often highly trusted by those whānau in need’.68 District health boards too highlighted the impact of Māori providers on vaccination rates. Clinical leaders at the former MidCentral District Health Board, where Māori vaccination coverage exceeded the national average, described ‘an amazing Māori response… the Māori nurses that worked with them, the iwi, the NGO providers… just the way te Ao Māori engaged with their people’. It was a similar story with Pacific providers, whom the Ministry of Health later praised for providing ‘flexible, adaptive, by-Pacific-for-Pacific’ vaccination delivery that met the needs of their communities.

For providers at the front line of the vaccination rollout, there was a mix of successes and frustrations. In Ōtautahi, Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu told us of a long wait before the district health board gave their vaccinators the mandate they needed to start ‘vaccinat[ing] our communities, in our way, in our spaces’. But once they were up and running, the impact was immediate:

“Our health and social service organisations stepp[ed] up, our marae stepp[ed] up and work[ed] together… Our Papatipu Rūnanga, we run community vaccinations, kaumātua and whānau from all around the area, no matter what iwi, we just contact everyone in our community and run big vaccination days at our marae, utilising local Māori health and social service agencies to provide support, but also staff from the PHO would come in.”

At the other end of the country, Māori health provider Hauora Hokianga said their COVID-19 response was hampered by funding limitations and uncertain availability. Government and district health board funding became available with little notice or discussion about what was needed most on the ground. ‘Putea bombs … came out of the sky’, they said, along with an expectation that they would be able to deliver at pace, especially during the Delta outbreak. The pressure took a heavy toll on health workers. On the other hand, the pandemic environment made it possible to secure some long-needed resources, including funding for a van to provide mobile healthcare and vaccinations.

According to Hauora Hokianga, some Ministry of Health directions for the rollout – especially the phased approach to vaccination – simply didn’t work for their communities, which were rural, widely dispersed and had a younger age profile than the general population. Older family members were often brought to vaccination sites by younger whānau who weren’t yet eligible under the sequencing framework.69 But as providers told us: ‘We weren’t going to turn whānau away who came to get vaccinated as they wouldn’t come back. We had a little mantra … “one more is one more than we had before”.’ When vaccinators ran out of supplies, ‘we just winged it and other providers supported us with their excess vaccines’. Good relationships and communications with other providers (‘the kūmara vine’) helped them get through.

In Tāmaki Makaurau, Ngāti Whātua Ōrākei, Whai Māia – which provides cultural and social support for the people of Ngāti Whātua Ōrākei, including through healthcare services – also described developing a bespoke ‘outreach’ approach. ‘[That’s] when it took off for Māori vaccination rates and it [was] all about engagement. The centre does not attract Māori – you have to go out to the community.’ They used five camper vans (adapted to keep the vaccine at the required temperature) and a team of seven vaccinators who could deliver 300–500 vaccinations in a three-hour stint. Ngāti Whātua Ōrākei played a key role in a rangatahi-led mass vaccination weekend held at Eden Park| Ngā Ana Wai in November 2021, targeting young people.70

Vaccination clinic run by Ngāti Whātua Ōrākei (Photo supplied by Ngāti Whātua Ōrākei)

In Kaitaia, Māori primary healthcare providers emphasised the need to tailor the rollout for their local communities, where many lacked trust in Government and anti-vaccination sentiment was high. They developed their own resources, interpreting Government requirements and guidance for the local context. The ANT Trustxiii – which set up the border control and other protective strategies for the community during COVID-19 – used monetary vouchers to incentivise vaccination uptake. It was effective in the short term, although they considered that ‘incentives shouldn’t be necessary if whānau were better connected with [the] health system’. Far North providers were generally frustrated by what they saw as a lack of trust and resourcing from central government during the pandemic response; it was very ‘top-down’, they felt, with few ways for providers to give feedback or contribute to decisions.

Many Māori and Pacific providers were frustrated at not being enabled to lead the vaccination drive for their communities earlier. There were various barriers, including the Ministry of Health’s initial preference for centralised vaccination sites. ‘[Pacific community providers] knew the models that were going to work… family-centred, drive-throughs, community pop-ups and outreach… these were the approaches that we put forward. But they were pushed back because the focus was on setting up fixed vaccination sites.’ According to the National Hauora Coalition, the country’s largest Māori-led primary health organisation, ‘the system didn’t give permission or provide for different access options for vaccinations – after hours, drive through or whole whānau. We had to battle the political arguments about mass vaccination sites’.

Others shared providers’ frustration at not being brought into the vaccine rollout earlier. Sir Brian Roche, a key independent advisor to ministers and officials throughout the pandemic response, was one.xiv He described a failure to unleash ‘the power of the community to respond and to lead’ – backed by resourcing – as a weakness of the pandemic response overall. In relation to vaccination specifically, he said: ‘What a wasted opportunity. When they finally began to use the community to vaccinate, the rates went up exponentially.’

7.3.3 The procurement process balanced the principles of prudent investment with the need to obtain an effective COVID-19 vaccine in a context of uncertainty

We have already set out the key steps in the vaccine procurement process the Government embarked on in 2020. The portfolio approach (used by many countries) was an appropriate investment that resulted in the purchase of an effective vaccine. As the vaccine taskforce advised ministers in July 2020, ‘traditional vaccine procurement approaches are not suitable for securing a product that does not yet exist’ and for which global demand would be fierce.71

While the possibility of domestic production was initially presented as one of three potential routes to obtaining a vaccine (alongside multilateral agreements such as COVAX and direct purchase from global manufacturers), limited experience with human vaccine production meant local manufacturing was an unlikely option. Aotearoa New Zealand eventually obtained COVID-19 vaccines by entering directly into advance purchase agreements with international pharmaceutical companies. The vaccine taskforce was supported in this endeavour by the provision of high-quality scientific advice to inform decision-making on which vaccine candidates were the most promising.72

It took time for vaccine doses to reach Aotearoa New Zealand, adding to the challenge of organising the national immunisation programme. While some accounts suggested New Zealand received lower priority by vaccine manufacturers and distributors in the vaccine supply chain, others rejected this suggestion, and we found no evidence to support it. When potential supply shortages emerged at a critical point in the vaccine rollout, alternative supplies were secured through agreements with other countries (supported by effective relationships at the leadership level). These findings illustrate the importance of international relationships and forward planning in securing essential supply chains in the context of a pandemic.

7.3.4 The regulatory approval process for COVID-19 vaccines was accelerated but still ensured their safety and efficacy were properly assessed

Before any vaccine can be used in Aotearoa New Zealand, it must be approved for use by Medsafe under the Medicines Act 1981. The approval process is intended to be objective and transparent, and to give the public confidence that medicines meet acceptable standards of safety, quality and efficacy, taking into account the specific New Zealand context and population.73

Given the urgent need to secure a safe and effective COVID-19 vaccine, Medsafe streamlined its administrative processes so that vaccine candidates could be assessed ‘at the earliest possible time’, without compromising the integrity of the approval process.74 Pfizer applied for Medsafe approval for its vaccine in October 2020.

As usual, Medsafe undertook expert review of evidence that Pfizer provided – albeit on a rolling basis, for speed – about the vaccine’s efficacy and safety in clinical trials. Again, as it normally does, Medsafe also assessed the vaccine’s expected benefits and risks. It granted the vaccine provisional approval on 3 February 2021, three months after Pfizer had applied.

We received a small number of public submissions from people who cited a lack of adequate testing and trialling as the reason they opposed the COVID-19 vaccine (though not necessarily other vaccines): ‘I am not against jabs as I have so many but I am against getting the covid jab as it didn’t have all the safety stages complete’. Few commented specifically on Medsafe’s approval process. One submitter who did said the regulator should ‘be free of government and big pharma influence, to enable an unbiased and professional assessment of any future vaccines and medicines’. However, many submitters appreciated that the Government obtained the vaccine it found to be the most effective and safe, and were impressed at the level of research that went into the choice of vaccine.

The evidence we considered indicates Medsafe followed its usual process to properly assess the efficacy and safety of COVID-19 vaccines, albeit on an expedited timeline. Arguably, its review of the Pfizer vaccine was even more rigorous than those of regulators in other countries. At the time, Pfizer had already been approved for use in the United Kingdom, United States and Australia, meaning Medsafe was able to review the most up-to-date evidence on vaccine efficacy and safety – including recent data that had not been available to regulators in other countries. This provided an extra level of reassurance that was welcome, given this was an entirely new product that was developed and trialled under urgency. At the same time, Medsafe’s approval process did not delay either procurement or rollout of the vaccine, with immunisations starting as soon as practicable after the first vaccine doses arrived in the country.75

We also note that in March 2021, the High Court rejected an application for an interim injunction that would have halted the vaccine rollout.76 The applicants argued that provisional approvals under section 23 of the Medicines Act 1981 were intended only for new medicines used on a ‘limited number of patients’; this provision did not apply to the Pfizer vaccine since the Government intended rolling it out to the entire adult population of Aotearoa New Zealand. In her decision, the judge observed ‘it is difficult to see how the assessment process could, in the circumstances, have been more thorough’ and that the evidence showed ‘a number of layers of reflection and review in addition to those that would ordinarily be expected in a provisional consent assessment’.77 Parliament later passed an urgent update to the Medicines Act 1981 to remove the legal risk. While the judgment affirmed the integrity of Medsafe’s approval process, it also highlighted what we consider a recurrent problem in the response to COVID-19: the risks of applying existing legislation to new and unanticipated circumstances arising in a pandemic. We return to this issue in our lessons for the future.

xi In December 2021, the Health Quality and Safety Commission reported that ‘once supported to lead their own approaches, significant increases in vaccination rates for both Māori and Pacific peoples have been achieved’. See A window on quality 2021: COVID-19 and impacts on our broader health system (Part One), p 32, https://www.hqsc.govt.nz/assets/Our-data/Publications-resources/COVID-Window-2021-final-web.pdf Health Quality and Safety Commission review).

x Coverage in the population aged 15 years and over, based on our analysis of vaccination data provided by the Ministry of Health.

xii Group 3 described those in the general population who were first in line to receive the COVID-19 vaccine. This included older adults (aged 65 years and over) and people with an underlying health condition that placed them at increased risk of severe outcomes from COVID-19 infection.

xiii Aupōuri Ngāti Kahu Te Rarawa (ANT) Trust

xiv Among other responsibilities, Sir Brian Roche led the first rapid review of all-of-government arrangements (April 2020) and chaired the COVID-19 Independent Continuous Review, Improvement and Advice Group from April 2021 to June 2022. This group provided regular advice to the Minister for COVID-19 Response.