5.4 What happened: preparing the wider health system to cope with COVID-19 cases I aha: te whakarite i te pūnaha hauora whānui kia tū pakari ki ngā kēhi KOWHEORI-19

Beyond strengthening public health measures to stop the spread of the virus, the health system also needed to prepare for a potentially dramatic influx of people unwell with COVID-19, should community transmission become established. As noted earlier, Aotearoa New Zealand’s healthcare infrastructure was under strain in many parts of the country before the pandemic and was not well set-up to care for large numbers of people with contagious respiratory infections, while keeping staff and other patients safe.

As in other parts of the world, prior to the arrival of COVID-19, delivery of healthcare in Aotearoa New Zealand was heavily reliant on face-to-face contact between health workers and sick people. This created additional risk in the context of a pandemic. Hospitals and other healthcare services therefore needed to implement changes that would allow them to care safely for people with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 and prevent the virus from spreading at their facilities. Such changes included upgrading buildings (or changing how they were used), introducing new infection control measures (or expanding existing ones), and managing who came into health facilities.

Several guidelines and frameworks were developed to help health and disability service providers assess their level of risk from COVID-19 and escalate or relax infection control measures (including visitor restrictions) accordingly. These frameworks were also intended to ensure a degree of national consistency in operational decisions, and to inform decision-makers about how much to defer or reprioritise non-COVID-19 healthcare services to manage COVID-19-related demands.

Aotearoa New Zealand’s healthcare infrastructure was not well set up to care for large numbers of people with contagious respiratory infections.

5.4.1 Changes in healthcare facilities to provide safe care in a respiratory pandemic

The state of healthcare infrastructure in general, and hospital facilities in particular, was negatively impacting the health system even before the arrival of COVID-19.

In the course of our Inquiry, we heard about a range of pre-existing challenges that made it difficult for healthcare facilities to reduce the risk of cross-infection from a contagious respiratory illness like COVID-19. These included:

- Aspects of building layout that made it difficult to separate potentially infectious patients (for example, emergency departments connected to wards via a single corridor).

- Ventilation systems that were not suited to reducing disease spread via airborne particles.

- A shortage of negative pressurexv rooms.

- Single nursing stations that made it hard to keep those working with infectious patients separate from other staff.

- Lack of suitable space near entrances and exits for correctly changing into and out of personal protective equipment (PPE).

While these issues were particularly prominent in hospitals, we also heard that many community health services and primary care facilities were poorly designed for separation of infectious and non-infectious patients and for appropriate ventilation and air flow.

The consequences of these infrastructure challenges for managing an outbreak of a highly infectious disease like COVID-19 became quickly apparent.

5.4.1.1 New patient management protocols and workflow processes

Hospitals undertook substantial work to adjust patient management and workflow processes in order to keep patients with respiratory symptoms (or confirmed COVID-19 cases) separate from others.

Such adjustments included redesigning work spaces,34 physically separating patients with respiratory symptoms as soon as they entered an emergency department, testing patients for COVID-19 at hospital entrances, setting up separate COVID-19 wards (for example, Auckland Hospital converted two wards for this purpose), and rostering staff to work in separate groups to limit their potential exposure to COVID-19.

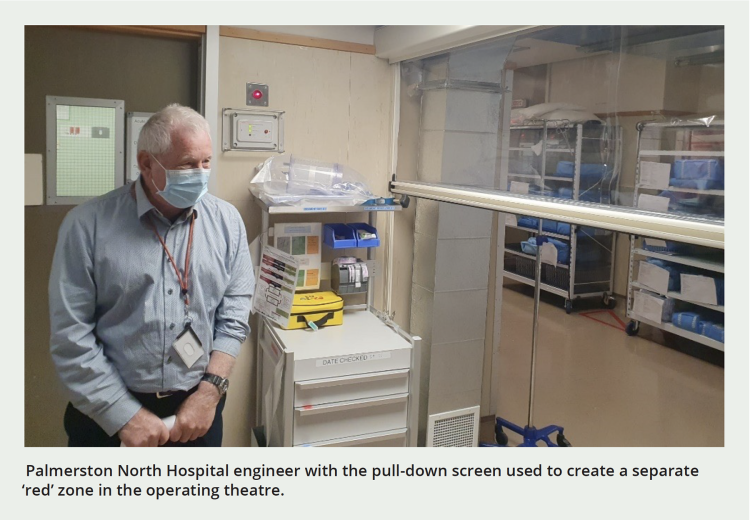

How each hospital designed and implemented these changes was shaped by the age and quality of their existing infrastructure. Options for improving ventilation and patient flows were more limited where buildings were outdated, and changes required a mix of pragmatism and innovation. For example, staff at Palmerston North Hospital (which had longstanding issues with outdated facilities)35 used pull-down screens to create separate ‘red’ zones for COVID-19 patients in the operating theatre and intensive care unit and retrofitted a substantially improved ventilation system.

Palmerston North Hospital engineer with the pull-down screen used to create a separate ‘red’ zone in the operating theatre.

5.4.1.2 Shoring up capacity to care for ventilated patients

The ability to care for patients requiring mechanical ventilation (when a machine helps someone to breathe) is an important aspect of health system capability in a pandemic. It was particularly important for COVID-19: people who became very sick with the virus often required ventilation. Sick patients who require ventilation are usually cared for by specially trained staff in a hospital’s intensive care unit (ICU), although ventilation can also be provided in other parts of the hospital (such as operating theatres and high-dependency units).

New Zealand’s intensive care capacity was lower than in many other countries at the start of the pandemic. A report by the OECD noted the country had 3.6 ICU beds per 1,000 population (compared with an OECD average of 12.0).36 This was well below the capacity in countries such as Italy and Spain, where hospitals had been overwhelmed in the early stages of COVID-19. Global demand for ventilators was soaring, with orders far exceeding global supply.37

Capacity to care for ventilated patients was therefore an area receiving a lot of attention in the early pandemic response. Cabinet agreed to support additional ICU capacity as part of an initial funding boost for the health response on 17 March 2020. On 31 March 2020, the Minister of Health told the Epidemic Response Select Committee that considerable progress had been made in preparing for a surge in COVID-19 admissions, including ‘a huge amount of work […] to determine how we can scale-up that ICU capacity’. This included securing additional ventilators, repurposing operating rooms, and running refresher and new training courses to ensure there was sufficient staff capability to care for ventilated patients.38

The importance of capacity to care for ventilated patients was reinforced by the COVID-19 Ministerial Group on 9 April 2020 when it agreed the criteria to be considered when deciding to move between alert levels. These included satisfying the Director-General of Health that there was sufficient general health system capacity, including workforce and ICU capacity.39

Weekly situation reports to ministers attempted to track ICU and ventilator capacity. As early as 29 March 2020, it was reported there was ‘sufficient’ capacity with 533 ‘ventilated ICU beds’ available.40 An update on 3 May 2020 again reported 533 ventilators in DHBs, with another 357 ventilator machines on order. A further 247 ‘potential ventilators’ were available in private hospitals and other providers.41 While physical spaces and ventilator units were identified fairly readily, a more challenging issue was training a pool of staff who could provide care for ventilated patients – which is a highly specialised skill. An update from early June 2020 noted that over 500 doctors and 800 registered nurses had been registered as part of a ‘surge capacity database’ listing around 10,000 people from the wider health sector, although it is not known how many of these were capable of caring for ventilated patients. Of this ‘surge capacity’, the update noted that 33 had been deployed into roles, but it was not clear whether these roles included this responsibility.42

While these reports demonstrate significant effort and at least some potential to surge capacity to care for ventilated patients, the Inquiry saw no evidence of a sustained ability to increase this capacity during the first 18 months of the pandemic response. According to the Ministry of Health, despite the early availability of funding, ICU capacity in July 2022 was similar to that at the start of 2020, with national numbers remaining the same at around 260. In November 2021, Cabinet established a contingency fund to increase ICU capacity, and in February 2022 the Ministry of Health sought to draw on it to increase critical care bed numbers to around 345 beds (including staffing). The Ministry advised us that – by January 2024 – funded ICU capacity was 312.

We were unable to ascertain what number of ventilated patients the health system could have surged capacity to care for, had COVID-19 case numbers and hospitalisations dramatically increased. Certainty about surge capacity will be important for future pandemics.

5.4.1.3 Retrofitting and upgrading hospital facilities

As well as changing patient management and workflow processes to improve infection control, many hospitals also undertook extensive retrofitting to reduce the likelihood of COVID-19 being transmitted between patients. As noted previously, this work typically focused on improving ventilation and managing the flow of patients so people with respiratory symptoms or confirmed COVID-19 could be physically separated from other patients. Many hospitals installed air purification units (also known as HEPA filters or ‘scrubbers’) to remove airborne particles and reduce the risk of droplet spread.

We heard differing accounts of the extent to which there was central support or guidance for this upgrading work. Health officials told us the Ministry ‘played a strong coordination role’ by meeting regularly with Chief Medical Officers and DHB chairs to check on progress. In contrast, we heard from some hospital staff that they received limited practical guidance on what was expected by way of retrofitting or what standards were required for building ventilation. The Royal New Zealand College of Urgent Care (the peak body for urgent care medicine) told the Inquiry that there was ‘no official guidance available from the Ministry about the mitigation of SARS-CoV-2 transmission by ventilation or air filtration’.

While additional funding ($100 million) was made available to hospitals to support this upgrading work, this wasn’t announced until December 2021.43

As a result, we were told that hospitals developed their own approaches to upgrading their physical infrastructure and relied heavily on the knowledge of their own staff. As one stakeholder put it, ‘each hospital did its own thing’. Not everyone viewed this as a problem. Some staff found it enabling to be allowed to ‘just get on with it’ and ‘not be paralysed by the need for perfection’. According to one: ‘We were permitted to take risks, to make decisions without having to go through burdensome processes’.

5.4.2 New infection control practices

In material provided to us in evidence, the Ministry of Health has acknowledged that ‘there was no national infection prevention and control capability at the start of the pandemic’.

This was quickly recognised as a gap, with efforts made to embed suitable expertise to review evidence and issue guidance about such matters as hand hygiene, mask use, physical distancing and ventilation. In the context of the pandemic, a range of new infection control practices were introduced – including COVID-19 screening in emergency departments, separate workflows and staff teams to manage patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19, and dedicated COVID-19 wards.

For health workers, the initial absence of such guidance, and later its frequently changing nature, created additional pressures during an already very challenging period. We heard from numerous professional bodies and colleges representing different healthcare workers about the stresses this placed on their members, especially early in the pandemic when there was limited evidence about the virus, its spread, and what worked to keep staff and patients safe.

There were repeated references in our direct engagements to New Zealand’s lack of expertise, capacity and central coordination in infection prevention and control, which was referred to as one of ‘the Cinderellas of the health system’. A specialist body told the Inquiry that ‘there were not enough trained staff’ to ensure adequate infection prevention and control practices across all aspects of the COVID-19 response.

These challenges were evident in primary and community health settings as well as hospitals. We heard that running GP and outpatient clinics under more stringent infection control measures meant patient appointments had to be spaced further apart to maintain social distancing and allow time to sanitise equipment, creating extra workloads for staff and longer wait times for patients.

5.4.2.1 Access to personal protective equipment (PPE)

PPE was an important part of infection prevention and control in healthcare settings, benefitting patients and staff alike and helping to maintain people’s access to health services. However, accessing it was a particular pressure point for many health workers during the pandemic.

Under the New Zealand Influenza Pandemic Plan 2017, DHBs were responsible for maintaining PPE stocks. It was assumed at the start of the pandemic response that this equipment would be available (and adequate) straight away. However, it was quickly established that much of the stock had not been well maintained or rotated and was now out of date and unfit for use.44 We are not aware of evidence that quantifies how serious these stock issues were, but we heard from senior health officials we engaged with directly that they were considered serious enough that they might compromise the health system’s ability to prevent or mitigate a COVID-19 outbreak.

The Ministry of Health managed the procurement and distribution of PPE for publicly-funded health workers. Under normal circumstances, the Ministry would spend about $25 million a year on PPE. By 30 June 2020, it had spent approximately $200 million to procure, store and distribute more than 46 million items of PPE, with another 165 million on hand ready to be deployed.

Centralised procurement and distribution were effective in providing PPE to hospitals, but worked less well for community-based services. We heard from many organisations and individuals about health workers in both primary and community care having difficulty getting PPE during the pandemic. Those affected included employees in general practices, hospital and community-based midwives, home care and disability support workers, pharmacists, and aged residential care workers.45 Difficulties in getting PPE, or the right PPE, also contributed to a slowing down of service delivery. In early 2020, urgent care doctors were so concerned about access to PPE – and a perceived lack of information about whether, when, and what kind of PPE would be made available to them – that some went so far as to source their own, including by importing it directly.

5.4.2.2 Infection control and visitor policies in hospitals and aged residential care facilities

For most of the pandemic period, DHBs had strict policies for those visiting or supporting patients in hospital. In general, no one could enter if they, or the patient they were visiting, had or were suspected of having COVID-19.

At ‘red’ and ‘orange’ hospital alert levelsxvi – alongside other increasingly stringent infection control measures – no visitors were allowed (or could only be permitted by a clinical nurse manager or senior manager on shift; in such cases, only one visitor or legal guardian was granted access).46 At all levels visitors needed to follow hand hygiene and PPE requirements, participate in contact tracing, and could expect to be turned away if unwell with COVID-19 symptoms.

These strict hospital visiting policies were intended to protect patients, staff, visitors and the wider public against COVID-19 by limiting potential exposure and transmission between patients and their visitors and support people. The restrictions were intended to be adjusted according to the DHBs’ own alert level status under the National Hospital Response Framework (see section 5.4.3).47 However, in practice, there were instances where DHBs diverged from the national approach, with some using stricter policies than it would suggest.48

Visitor restrictions were also applied in aged residential care. Aged residential care residents are more vulnerable than the wider population to the adverse impacts of viruses in general, and were at particular risk of contracting COVID-19 due to their close contact with others.49

These risks came into sharp focus early in the pandemic, when several early clusters were located in such facilities in Aotearoa New Zealand. A subsequent review found the sector had reasonable infection control practices and readiness for infectious outbreaks, and these were quickly activated.50

Some aged care providers moved their facilities into lockdown-like conditions earlier than the rest of the country. Steps taken within aged care facilities included introducing visitor restrictions, limiting contact between residents, and isolating residents by themselves or within bubbles as required (although this was challenging for some residents with dementia). In many facilities, lockdown-like facilities were maintained for much longer than the time the rest of the country spent at Alert Levels 3 and 4.

By March 2022, the Minister of Health had become concerned about the effects of extended social isolation on aged care residents. By this time, the general population was living with lower restrictions under the new COVID-19 Protection Framework, or ‘traffic light’ system, but many residents of aged care facilities remained subject to strong restrictions.

In May 2022, the Ministry of Health issued new guidelines for safe visiting and social activities in aged residential care. These outlined a series of principles, including that ‘social connection and physical contact with whānau are fundamental to the health and wellbeing’ of aged care residents, and that it was essential to enable safe visiting, social activities and outings even during a COVID-19 outbreak or when community transmission was widespread.51

...social connection and physical contact with whānau are fundamental to the health and wellbeing of aged care residents.

5.4.3 Prioritising services and redeploying resources in response to COVID-19 risk

As well as making changes to patient management systems, retrofitting and improving hospital facilities, and issuing new infection control guidelines and equipment, hospitals and other health services had to be ready to reprioritise their services and redeploy their resources in readiness for a potential influx of COVID-19 cases; if nothing else, the frightening scenes of overwhelmed hospitals in other countries in early 2020 had shown the importance of this.

As mentioned earlier, several national guidelines helped health services not only to escalate or relax infection control measures in response to COVID-19, but also to make decisions about how much to adjust non-COVID-19-related services.

One key framework was the National Hospital Response Framework, which was developed by the Ministry of Health in collaboration with DHBs in March 2020. This aimed to support DHBs to safely deliver and maximise patient access to non-COVID-19 hospital services (such as in-patient care, surgeries and specialist appointments), while also protecting hospital capacity to deal with COVID-19-related demand as it arose.52

The national response framework provided guidance on how to scale infection control measures and clinical services up or down according to different levels of perceived COVID-19 risk, and DHBs’ capacity to manage this risk.

There were four ‘alert levels’ ranging from ‘green’ (low perceived risk of COVID-19 impact) to ‘red’xvii (high perceived risk of ‘severe’ impact).53 Different hospital facilities within a DHB, or even departments within a single hospital, could be at different alert levels at any given time. Each DHB was required to report their overall alert level to the Ministry on a daily basis, so that ‘a national view of escalation’ could be compiled.

The framework recognised that, even at times or in regions where there were no active COVID-19 cases, the provision of ‘business as usual’ care would need to remain prepared for a possible surge during an active pandemic. At the lowest, or ‘green’ level of risk, hospitals were expected to be ready for any COVID-19 cases that presented, although planned care continued as usual. Specialist clinics were also expected to continue, but remotely – for example by videoconference.

At the highest, or ‘red’ level of risk, hospitals were encouraged to discharge as many patients as possible and cancel any surgery not considered an emergency. This would ensure all possible capacity was available to respond to people presenting with COVID-19.

In practice, this system came to guide not only hospital-based care, but the overall provision of non-COVID-19 health services during the response. A parallel framework was developed for primary and community health services, which evolved over time.54 DHBs were tasked with sharing their plans for managing hospitals at different (health) alert levels with primary and community providers,55 and it was expected that the primary and community sectors would respond to COVID-19 risk ‘in sync’ with the hospitals.56

xv Negative pressure rooms have high-flow ventilation systems that continually move air out of the room (and then out of the building), ensuring potentially contaminated air doesn’t recirculate back into corridors and other parts of the facility.

xvi The alert levels were specific to hospitals and (despite the similar terminology) were not the same as the national Alert Level System – see next section.

xvii Note that this traffic light system was distinct from the national Alert Level System and COVID-19 ‘traffic light’ system, as it was unique to the health system. It allowed DHBs to assess localised COVID-19 risks and their capacity to manage those, and also make decisions on service availability and infection control given those circumstances.