7.2 What happened I aha

7.2.1 Securing a vaccine

After the SARS-CoV-2 virus emerged in Wuhan at the end of 2019, international efforts to develop safe and effective vaccines moved at unprecedented speed. But how long it would take to complete trials, scale-up manufacturing, obtain regulatory approvals and distribute adequate supplies to meet global demand was unknown. The risk of failure was high: historically only about 20 percent of vaccines entering human trials resulted in a successful vaccine.1 Officials therefore advised the Government to adopt a flexible vaccine strategy and pursue ‘multiple concurrent approaches’ to securing vaccines. The working assumption was that at least 80 percent of the population had to be vaccinated before Aotearoa New Zealand could start moving on from the elimination strategy and its strictures.2

The Government announced its COVID-19 vaccine strategy on 26 May 2020. Aotearoa New Zealand would secure access as early as possible to a safe and effective vaccine, which would then be rolled out through a population-wide immunisation programme (whose details were still to be determined). Vaccine procurement would be overseen by a taskforce led by the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment. It included representatives from the Ministries of Health and Foreign Affairs and Trade, Medsafe (New Zealand’s medicines regulator), and Pharmac (responsible for national vaccine purchasing). Cabinet also allocated an initial $30 million to fund domestic and international vaccine research, and to explore the potential for local vaccine manufacture.3

At the end of June 2020, Aotearoa New Zealand formally expressed interest in participating in the COVAX Facility, a global initiative aiming to speed up development of COVID-19 vaccines and promote more equitable global access. At the same time, officials considered that ‘purchasing from an overseas manufacturer is emerging as the quickest and most likely route to securing a safe and effective vaccine for use in New Zealand’.4

In August 2020, Cabinet agreed to a vaccine purchasing strategy and funding envelope5 (on top of the initial $30 million investment in vaccine research and manufacturing capacity).6 Officials from the taskforce would negotiate advance purchase agreements directly with several pharmaceutical companies overseas. To manage the uncertain environment, a portfolio of vaccines would be secured: while this would likely result in greater quantities of vaccine than were actually needed, it offset the risk of some vaccine candidates becoming available later than others – or not at all – and the risk of some vaccines having less than desirable effectiveness or high adverse event rates.7

This ‘portfolio approach’ could be likened to an insurance arrangement, where it was accepted there would be some surplus or ‘wasted’ vaccine, in exchange for the certainty that at least one of the portfolio options would result in Aotearoa New Zealand having timely access to an effective vaccine. The approach anticipated that some vaccine doses would be sourced through COVAX, although only around 20 percent of the country’s immunisation needs were expected to be met from this source. In addition to purchasing vaccines for its own population, New Zealand would also supply vaccines to several Pacific nations including the Cook Islands, Niue and Tokelau.8

Meanwhile, the Ministry of Health had been developing a national COVID-19 immunisation strategy to roll out the vaccine across the country.9 In December 2020, Cabinet endorsed the strategy’s purpose: ‘to support the “best use” of COVID-19 vaccines, while upholding and honouring te Tiriti o Waitangi obligations and promoting equity’. Since vaccine supplies were likely to be limited until at least mid-2021, Cabinet agreed that immunisation would be prioritised via a sequencing framework ‘to ensure the right people are vaccinated at the right time’. Under the framework, the first groups to be immunised would be border and managed isolation and quarantine (MIQ) workers and their household contacts (judged to be at highest risk of COVID-19 exposure) followed by health and other high-risk workers and any high-risk household contacts. The vaccine would then be rolled out to the general population, starting with more vulnerable groups such as older people.10

On 12 October 2020, the Government announced the first advance purchase agreement, with Pfizer/BioNTech (Pfizer).11 The company would supply 1.5 million doses (enough for 750,000 people) of its ‘Comirnaty’ (BNT162b2) mRNA vaccine (commonly known as the Pfizer vaccine), subject to the successful completion of clinical trials and regulatory approval.

The initial batch of Pfizer vaccines (65,520 doses) arrived in New Zealand on 15 February 2021. Around three weeks later, the Government announced it had purchased another 8.5 million doses, to be delivered in the second half of 2021. Enough Pfizer doses had now been secured for everyone in the country to receive the necessary two shots.12 The Government subsequently also purchased Novavax, Janssen and AstraZeneca vaccines, but none of these were used as a first-line option in the immunisation programme.

7.2.2 Regulatory approval

Health officials were conscious of the need to conduct a ‘robust and comprehensive’ assessment of the COVID-19 vaccine that would ‘provide assurance to the public and withstand rigorous review’.13 It was therefore important that the Pfizer vaccine undergo independent assessment by Aotearoa New Zealand’s medicines regulator, Medsafe, even though it had already been approved for use in several other countries (including the United States and Australia).14 In addition to fulfilling regulatory requirements,i the approval process allowed experts to assess the vaccine’s expected benefits and risks with specific reference to the profile of the New Zealand population. It also allowed regulators to review the most up-to-date evidence on vaccine efficacy and safety – including more recent data that had not been available to regulators in other countries.

The Pfizer vaccine was provisionally approvedii by Medsafe at the beginning of February 2021,15 before the first doses arrived in the country. The approval process was undertaken on an accelerated time frame but followed the normal process, including review of company-provided data, requests for further evidence in response to specific questions, expert advice and review by the Medicines Assessment Advisory Committee.iii The Pfizer vaccine subsequently received full approvaliv in Aotearoa New Zealand in November 2023 under section 20 of the Medicines Act 1981. Medsafe continues to monitor the safety of COVID-19 vaccines and to review any adverse events following their use in New Zealand.16

Medsafe subsequently gave provisional approval for the use of COVID-19 vaccines produced by Novavax, Janssen and the University of Oxford/AstraZeneca,v although only the Novavax and AstraZeneca vaccines were ultimately used as alternatives to the Pfizer vaccine in Aotearoa New Zealand.

In addition to fulfilling regulatory requirements, the approval process allowed experts to assess the vaccine’s expected benefits and risks with specific reference to the profile of the New Zealand population.

International assessments of vaccine effectiveness and safety

Ongoing evidence reviews have continued to evaluate the Pfizer vaccine as effective in substantially reducing the risk of severe illness and death from COVID-19 and safe in terms of carrying a very low risk of serious adverse side-effects.17 Guidance from the World Health Organization’s Strategic Advisory Group of Experts on Immunisation notes that myocarditis (inflammation of the heart) is a ‘rare adverse event’ that can occur following administration of mRNA COVID-19 vaccines, including the Pfizer vaccine. While noting that myocarditis following vaccination is generally mild and responds to treatment,18 the World Health Organization advises that people receiving the COVID-19 vaccine ‘should be instructed to seek immediate medical attention if they develop symptoms indicative of myocarditis or pericarditis, such as new onset and persisting chest pain, shortness of breath, or palpitations following vaccination’.19

7.2.3 The rollout begins

Because vaccine supplies were initially very limited, the vaccine rollout was sequenced to prioritise those considered to be at greatest risk of COVID-19 transmission, infection or illness. The first people to be vaccinated (the frontline vaccinators themselves) received their first doses on 19 February 2021, followed by border workers in both the North and South Islands. In March 2021, Cabinet finalised the sequencing framework that would guide the vaccine rollout. Four population groups would be vaccinated in sequence according to their risk profile:

- Group 1: border and MIQ workforce, and their household contacts;

- Group 2: frontline workers, medically vulnerable people (people aged 65 years and older, people with underlying health conditions and disabled people) and people living in high-risk environments – including people in long-term residential care, older Māori and Pacific peoples living in intergenerational households and people living in South Auckland (the Counties Manukau district);

- Group 3: all other medically vulnerable people (people aged 65 years and older, people with underlying health conditions and disabled people); and

- Group 4: the rest of the population aged 16 years (later lowered to 12 years) and older. Vaccinations would be staggered by age group.20

From March 2021 onwards, the Pfizer vaccine was rolled out nationwide to each group in turn, with people receiving their first two vaccine doses three weeks apart (later increased to six). The mass vaccination phase started on 28 July 2021 when Group 4 became eligible, beginning with those aged 60 or older.

A rollout on this scale represented a significant operational challenge, particularly given the initial requirement that the vaccine be stored at ultra-low temperatures (-70°C). COVID-19 vaccination ‘hubs’ were set up in carparks, stadiums and other large sites to cope with the volume. From a starting point of 2,000 doses a day, more than 50,000 doses a day were being administered by late August 2021.21

The vaccinator workforce needed to grow to support the rollout as it expanded. Earlier in the pandemic, professional bodies such as the Nursing Council of New Zealand had supported the Ministry of Health to recruit trained health professionals back into the workforce and it did so again now, issuing interim practising certificates to trained nurses who wished to rejoin. An amendment to the Medicine Regulations allowed the Director-General of Health and Medical Officers of Health to authorise others – including non-regulated healthcare assistants and pharmacy technicians – to become COVID-19 vaccinators once they had received appropriate training.

The arrival of the Delta variant in mid-August 2021 prompted a rethink of Aotearoa New Zealand’s vaccination settings. Technical health expertsvi recommended that children aged 12 to 15 years should be vaccinated, noting that lowering the eligibility age would help ensure equitable vaccination coverage among Māori and Pacific peoples: young people represented a greater proportion of those communities (compared with the overall population) and these groups were at higher risk from COVID-19.22

The arrival of Delta also prompted a shift away from large-scale vaccination ‘hubs’ towards a greater number and diversity of vaccination sites to help make access easier for ‘harder to reach populations and … those with mobility issues’. People could now be vaccinated in general practices and pharmacies; there was greater involvement of Māori, Pacific and other community-based providers; and many tailored initiatives were launched to improve access for people with disabilities. These efforts supported increased vaccine access and uptake, to the point that Aotearoa New Zealand risked a supply shortage of the Pfizer vaccine in mid-September 2021. Continuity of vaccine supply was secured via agreements with Spain and Denmark, supported by direct engagement between the Prime Minister and her counterparts in those countries.

As the population gained protection from increased vaccination coverage, the Government started preparing for a shift in its approach. This included plans for a gradual reopening of borders and ‘more measured domestic restrictions’ – in other words, an end to lockdowns. On 22 October 2021, the Prime Minister formally signalled the country would move from elimination to a minimisation and protection approach (and from the Alert Level System to the COVID-19 Protection Framework) when 90 percent of the population in each district health board area was fully vaccinated. The move was later scheduled for 2 December 2021, by which time the Ministry of Health estimated that 86 percent of the eligible population was fully vaccinated.

On 16 December 2021, the Ministry of Health announced that 90 percentvii of the eligible New Zealand population had received two doses of the COVID-19 vaccine.23

7.2.4 Vaccine boosters

By mid-to-late-2021, evidence was growing internationally that protection against COVID-19 infection and severe disease declined in the months following vaccination. By November 2021, official documents from health officials were speaking to this evidence that the protection against COVID-19 infection and severe disease that vaccines offered appeared to wane in the months following immunisation. On 8 November, Medsafe updated its provisional approval for the Pfizer vaccine to include administration of a third ‘booster’ dose.24

The booster rollout started in November 2021, prioritising those at increased risk of COVID-19 exposure or illness – including frontline health workers, all people aged 65 years or older, Māori and Pacific people aged 50 years or older and those with medical vulnerabilities.25 In practice, this meant around two thirds of New Zealanders were eligible for a vaccine booster.26 Sustaining as high levels of population immunity as possible was critical, particularly given the emergence of another highly transmissible COVID-19 variant, Omicron, around this time.viii

7.2.5 Sustaining population immunity

Given the greater social freedom and mobility allowed from December 2021 under the new protection framework, Omicron was seen as presenting a very real threat. With the move from elimination to minimisation and protection (i.e. a suppression and mitigation strategy) and the highly infectious nature of Omicron, it was no longer feasible to avoid widespread COVID-19 transmission in Aotearoa New Zealand. The focus now was on using the COVID-19 Protection Framework to ‘flatten the curve’ and reduce the peak of infection through maintaining high vaccination levels accompanied by public health and social measures. Over time, population immunity would also be boosted as more people acquired – and recovered from – COVID-19 infection (a situation known as hybrid immunity27).

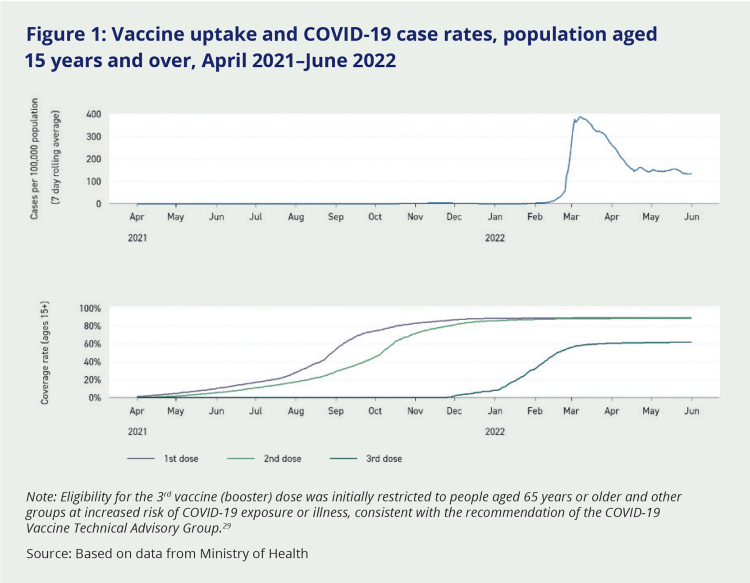

Efforts were made to maximise vaccine protection before Omicron infection became widespread in Aotearoa New Zealand. By early 2022, small quantities of AstraZeneca and Novavax COVID-19 vaccines had been made available for adults unable or unwilling to receive mRNA vaccines like Comirnaty (commonly known as Pfizer)ix in order to encourage vaccine uptake. The original vaccine booster interval of six months was reduced to four and then three months.28 Rapid uptake of booster doses meant population immunity among the most vulnerable groups was high at the point Omicron was peaking (see Figure 1), meaning hospitalisation and death rates were much lower than in other countries (see Chapter 5).

Figure 1: Vaccine uptake and COVID-19 case rates, population aged 15 years and over, April 2021–June 2022

Note: Eligibility for the 3rd vaccine (booster) dose was initially restricted to people aged 65 years or older and other groups at increased risk of COVID-19 exposure or illness, consistent with the recommendation of the COVID-19 Vaccine Technical Advisory Group.29

Source: Based on data from Ministry of Health

By April 2022, the first Omicron wave was starting to ease. Restrictions were gradually relaxed, and progressive reopening of the border continued. Responsibility for purchasing and managing COVID-19 vaccines transferred from the Ministry of Health to Pharmac in July, although ministers continued to approve final purchasing decisions. The Government was by now developing a new approach for the long-term management of COVID-19, which would treat it more like any other respiratory infection. High levels of vaccination coverage and immunity across the population would be key. With this in mind, the Government announced on 28 June 2022 that everyone over 50 years could now receive a second booster (in other words, a fourth dose). Earlier, it had taken other steps to encourage vaccine uptake by amending the Medicines Regulations to expand the pool of vaccinators and allowing vaccinations to be given in more convenient and accessible places.

On 12 September 2022, the COVID-19 Protection Framework Order was revoked, ending the minimisation and protection approach and the ‘traffic light’ system. The last remaining vaccination mandates were removed on 26 September 2022.30 From then on, COVID-19 vaccinations became part of the national immunisation programme, available free of charge to everyone aged over 5 years. The Pfizer vaccine remained the main vaccine, with the number and frequency of recommended doses varying according to age and health status.

i The Medicines Act 1981 requires new medicines to be assessed and approved by Medsafe before being sold or supplied in New Zealand.

ii Medicine regulators in some countries (such as the United States and the United Kingdom) have emergency authorisation mechanisms that can be used where there is an urgent need for new drugs to be made available. Medsafe does not have an emergency approval mechanism, but can provide time-limited provisional approval in specific circumstances. This mechanism was used to approve use of the Pfizer Comirnaty COVID-19 vaccine.

iii A technical advisory committee that advises the Minister of Health on the risk-benefit profile of new medicines.

iv Full approval of Pfizer’s Comirnaty vaccine took account of data on the vaccine’s longer-term safety and efficacy. This data was not available at the time the initial (provisional) approval application was made because in late 2020 the vaccine had been in use for only a short period of time.

v The COVID-19 vaccine produced by Moderna was provisionally approved by Medsafe after the pandemic response period and was not used in New Zealand.

vi The Ministry of Health established the COVID-19 Vaccine Technical Advisory Group in early 2020. It comprised 14 experts including epidemiologists, virologists and laboratory science experts who provided the Ministry with information and specialised advice. Initially, the group met twice weekly, and then monthly.

vii Real-time estimates of vaccination coverage often differ from rates calculated retrospectively, when more comprehensive data is available (particularly in relation to numbers eligible for vaccination, i.e. the ‘denominator’). Based on data provided to our Inquiry by the Ministry of Health, we estimate that 86 percent of the population aged 15 years and over had received two vaccine doses by the end of 2021.

viii Vaccines such as Pfizer continued to provide a high level of protection against severe illness due to COVID-19, although this protection decreased over time. Vaccine-induced protection from transmission of COVID-19 was much less for Omicron than it had been for previous variants. The use of booster doses was intended to reduce transmission as much as possible (albeit less effectively than for previous variants) in order to flatten the peak of Omicron infection. It also provided significant protection against severe illness, reducing hospitalisations and deaths arising from Omicron.

ix mRNA vaccines contain the genetic code for the ‘spike protein’ present on the surface of the SARS-CoV-2 virus (COVID-19). Once the vaccine is administered, the human body reads the genetic code and makes copies of the protein. The immune system learns to recognise these proteins, enabling it to fight the virus when it encounters it.