6.3 Our assessment: economic impacts and responses Tā mātau arotake: ngā ōhanga o te mate urutā me te urupare a te Kāwanatanga

6.3.1 The initial package of economic measures was comprehensive and generous, and met its immediate aims

At a high level, this initial package delivered against its immediate aims. These were to support the public health response by maintaining economic activity, sustaining business confidence, protecting employment, protecting incomes, sustaining financial stability, and ensuring that all essential services were accessible. A 2021 OECD report indicated that, in doing so (initially at least), Aotearoa New Zealand had generated better economic and social outcomes than most other OECD countries. Initially, the Reserve Bank and the Treasury were also concerned that the health crisis could develop into a financial crisis. This too was successfully avoided. Moreover, it had achieved these outcomes with restrictions that were of comparatively short duration and, over the course of the pandemic, less stringent on average than in many other countries.41

Likewise, Aotearoa New Zealand’s monetary policy response was in line with those of other countries that successfully pursued the same intended short-term outcome: cushioning the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on their people.42 New Zealand maintained a relatively stable economic position, prevented large scale unemployment, supported people’s incomes, and the economy rebounded very fast in 2020 and 2021 – both in absolute terms and relative to other comparable OECD economies.

By and large, in terms of the initial (2020–22) macroeconomic impacts of the pandemic, as well as the economic policy responses to it, Aotearoa New Zealand performed comparatively well.43

Aotearoa New Zealand had generated better economic and social outcomes than most other OECD countries.

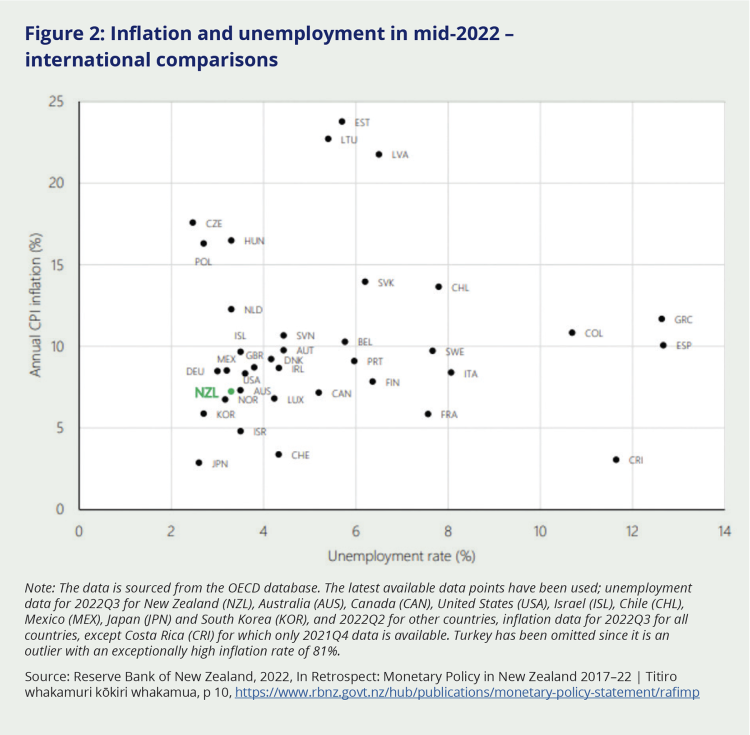

Figure 2: Inflation and unemployment in mid-2022 – international comparisons

Note: The data is sourced from the OECD database. The latest available data points have been used; unemployment data for 2022Q3 for New Zealand (NZL), Australia (AUS), Canada (CAN), United States (USA), Israel (ISL), Chile (CHL), Mexico (MEX), Japan (JPN) and South Korea (KOR), and 2022Q2 for other countries, inflation data for 2022Q3 for all countries, except Costa Rica (CRI) for which only 2021Q4 data is available. Turkey has been omitted since it is an outlier with an exceptionally high inflation rate of 81%.

Source: Reserve Bank of New Zealand, 2022, In Retrospect: Monetary Policy in New Zealand 2017–22 | Titiro whakamuri kōkiri whakamua, p 10, https://www.rbnz.govt.nz/hub/publications/monetary-policy-statement/rafimp

Figure 2 shows that in mid-2022, New Zealand performed well compared to other OECD countries in terms of both inflation and unemployment. But as we explain in this chapter the early generosity of New Zealand’s economic policy response – followed by the start of the reversal in monetary policy from October 2021, in combination with the impact of international events such as the war in Ukraine and ongoing supply shocks – led to deteriorating economic performance in terms of unemployment and real GDP growth.

6.3.2 The generosity of the initial response and the length of time it continued has slowed Aotearoa New Zealand’s subsequent economic recovery, and the effects continue to be felt

The success of the initial economic response – including the Response and Recovery Fund, and the monetary and fiscal policies that were adopted – had a flipside. From mid-2021 onwards, both the pandemic itself and the policy responses to it started having economic and social impacts across society, sectors and regions that were strong, unevenly distributed and negative. At the same time, the Government had to act to address the inflationary pressures and the sharp rise in public debt created by the initial response, within tight time constraints. Overall, these factors led to a slow and protracted medium- to long-term economic recovery, the effects of which are still with us in 2024.

To understand how this unfolded, it is necessary to go back to early 2020. Aotearoa New Zealand was then in a relatively stable economic position, with low interest rates and low public debt. Economic institutions were in reasonably good shape, with the independent operation of monetary policy now decades old and well-entrenched. Successive governments had created an ongoing ‘fiscal buffer’ of internationally relatively low levels of public debt (AAA rated by Standard & Poor’s) by the operation of generally fiscally responsible policies as required in the Public Finance Act 1989. As the COVID-19 response began, there was a sharp slowdown in economic activity and a drop in employment, both of which were unevenly distributed across industries and regions, as well as social groups.

This downturn was followed by an equally sharp economic rebound in the second half of 2020, reflecting the generosity and timeliness of the financial support packages put in place (see Figure 1). This reduced the adverse short-term economic impacts of the pandemic, but at the expense of contributing to a gradual climb in the cost of living and broader inflationary pressures including rising house prices. As we note elsewhere in this chapter, these impacts cannot be attributed exclusively to domestic policy responses; global developments (including the war in Ukraine) also played a significant role.

By the third quarter of 2020, real GDP (a measure of total production of goods and services) had already recovered to its pre-COVID-19 level, earlier than in any other OECD country.44 The unemployment rate fell quickly to a trough of 3.2 percent, its lowest level in 40 years (December 2021 quarter).45

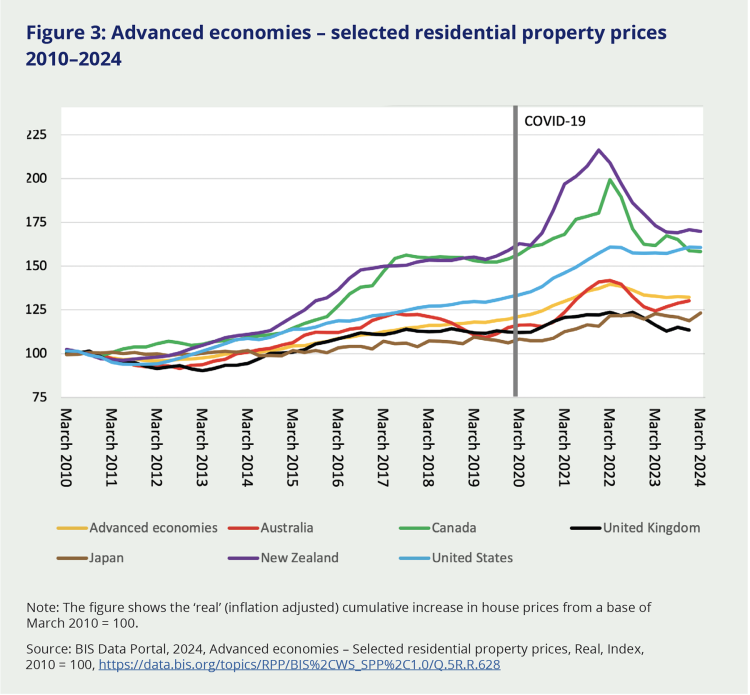

Accompanying the strong rebound in economic activity, but also reflecting severe supply-side constraints, were strong inflationary and cost-of-living pressures (including on food and petrol prices). House prices rose strongly throughout 2020 and 2021. Inflation began to rise quickly around mid-2021, fuelled initially by excess demand and pandemic-induced supply chain tensions, and later aggravated by the war in Ukraine.

In response, the Reserve Bank raised the Official Cash Rate by 525 basis points to 5.5 percent between October 2021 and mid-2023.46 The effects can be seen in increases to the Consumer Price Index during the period: the annual percentage change grew to 7.3 percent in June 2022, but had decreased sharply to 2.2 percent by September 2024.47

All these developments – high interest rates, the increase in government debt, sharply rising house prices (shown in Figure 3 in absolute terms and against other advanced economies) – have had adverse effects that are likely to be felt for some time to come. More generally, the arrival of COVID-19, and the policy measures used to manage the health impacts, may have reduced the productive capacity of the economy (causing more inflation for a given level of demand). See section 6.6, which addresses the ‘long tail’ effects of the pandemic and the policy responses to it.

Figure 3: Advanced economies – selected residential property prices 2010–2024

Note: The figure shows the ‘real’ (inflation adjusted) cumulative increase in house prices from a base of March 2010 = 100.

Source: BIS Data Portal, 2024, Advanced economies – Selected residential property prices, Real, Index, 2010 = 100, https://data.bis.org/topics/RPP/BIS%2CWS_SPP%2C1.0/Q.5R.R.628

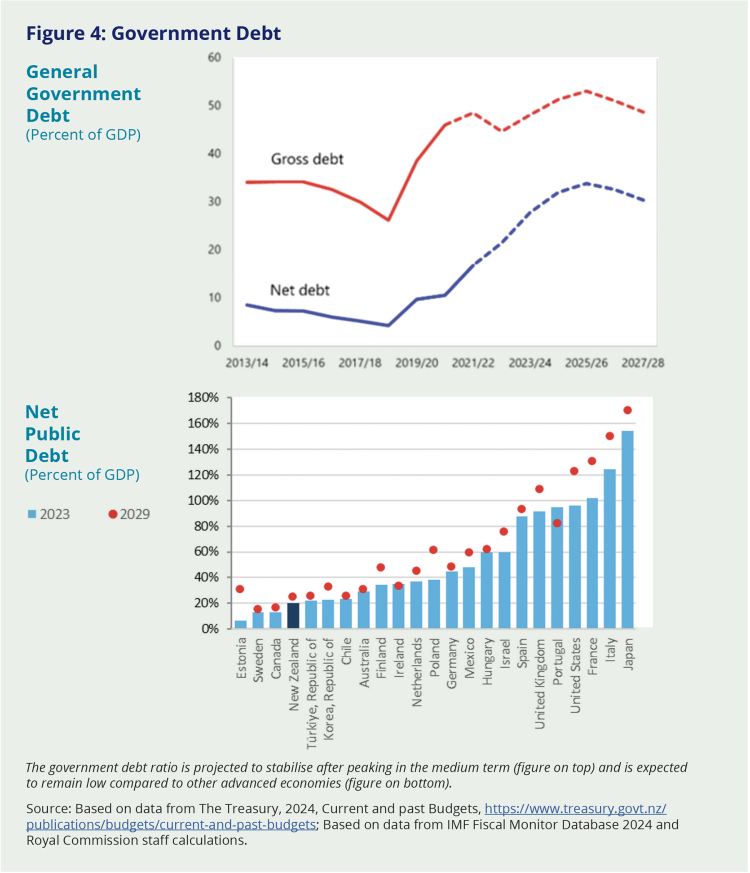

Most of the fiscal impact of the COVID-19 response (including the collateral fiscal effects of monetary policy, positive and negative), as well as the impacts of the economic downturn, are forecast to be absorbed by the Government’s balance sheet, via increasing borrowings (that is, through higher debt) and reducing net worth. Net core Crown debtx is expected to reach 43.5 percent of GDP by the end of the 2024–25 financial year,48 having been 19 percent of GDP at 30 June 2019.

By this measure, the Government’s balance sheet is healthier than most other countries, even though Aotearoa New Zealand’s fiscal response to the pandemic was relatively generous. Nevertheless, reports on the New Zealand economy by the OECD (cited earlier) and the International Monetary Fund49 both raised concerns about the fast and significant rise in net government debt, as shown in the top panel in Figure 4. The rise will also be considered in the next review of New Zealand’s international credit ratings, although this country’s comparatively strong international performance (see right-hand panel in Figure 4) will help counter any immediate threat to our credit rating.

According to Martin Foo, the Director of Sovereign and International Public Finance Ratings for United States-based credit rating agency Standard and Poor’s Global Ratings, the agency remained comfortable with the AAA credit rating it upgraded New Zealand to in 2021. ‘New Zealand is doing pretty well in a global context if you’re just talking about levels of credit ratings,’ Martin Foo told the New Zealand Herald in August 2024. ‘But there is no doubt, the response to the pandemic was costly. It did result in a big expansion in the size of government.’50 It should be noted that New Zealand enjoys the highest sovereign credit rating from Standard & Poor’s Global Ratings and Moody’s, while Fitch Ratings rates New Zealand at AA+, which has not changed since before the pandemic. Nevertheless, Martin Foo’s statement can be interpreted as a warning that we should be cautious.

“New Zealand is doing pretty well in a global context if you’re just talking about levels of credit ratings.”

Under the Public Finance Act 1989, governments are required to manage their expenditure and revenue policies to maintain prudent levels of public debt. Successive governments have taken the view that public debt needs to be relatively low for several reasons:

- As a small economy, Aotearoa New Zealand does not have the economic heft to cope with international shocks; much bigger economies have more scope to ride these out.

- New Zealand’s economy is not as diversified as many others, meaning that specific shocks may have a much bigger relative effect.

- New Zealand is also relatively highly exposed (as we have seen) to natural disasters such as earthquakes, etc.

- Low public debt offsets relatively high private debt in the New Zealand economy.

- Low debt also reduces the risk margin to be found in interest rates. This provides other benefits to the New Zealand economy, reducing the financing costs of investment and improving our access to international financial markets in the case of financial crises.

- Low debt also – obviously – reduces the fiscal burden of servicing debt.

Internationally, poor economic policies also result in higher risk premiums.

Fundamentally, all country-specific interest rates carry a risk premium within them. For example, New Zealand’s interest rates are typically higher than those for the United States. In part, this is because we are small and the United States is big (and therefore better able to absorb negative developments) and partly also because the $US is a reserve currency – meaning lots of currency players invest in the United States when things internationally look fragile, which keeps their interest rates lower. Internationally, poor economic policies also result in higher risk premiums. Essentially, arbitrage ensures our interest rates adjust to reflect these factors and maintain some stability in our exchange rate.

Figure 4: Government Debt

The government debt ratio is projected to stabilise after peaking in the medium term (figure on top) and is expected to remain low compared to other advanced economies (figure on bottom).

Source: Based on data from The Treasury, 2024, Current and past Budgets, https://www.treasury.govt.nz/publications/budgets/current-and-past-budgets; Based on data from IMF Fiscal Monitor Database 2024 and Royal Commission staff calculations.

The debt figures shown in Figure 4 are calculated using the International Monetary Fund’s Government Finance Statistics methodology. This differs from the methodology used by the New Zealand Treasury but is more comparable across countries.

With the benefit of hindsight, we have considered the factors that might lie behind this apparent ‘overshoot’ of macroeconomic stimulation – the monetary and fiscal expansion being too high for too long during the pandemic. While immediate attention might be drawn to the ‘least regrets’ stance taken at the beginning of the pandemic by both the fiscal and the monetary authorities, we believe this approach was fundamentally sound. Little was known about the nature and likely impact of the virus at that stage, apart from what might be inferred from the then-severe events unfolding overseas, in Italy and elsewhere.

As we have commented earlier in this report (see Chapter 2), adapting and planning for forthcoming possible scenarios during the ‘honeymoon’ period created by the undoubted initial success of the elimination strategy was generally slow. There was a tendency to hold on to existing public health and indeed other settings for too long. We think this factor also contributed here. Having said that, we recognise that the Reserve Bank did begin tightening monetary policy from October 2021, eventually raising the cash rate by a full 525 basis points. The Treasury, on several occasions, reinforced the need for exit strategies and recommended some pull-back on fiscal support. The Government did respond to these urgings – for example by changing the criteria for the subsequent rounds of the Wage Subsidy Scheme – but the overall picture was one of being cautious about change for too long.

There may have been other, more technical factors at play also. For example, the initial economic and financial response to the pandemic was largely viewed as a demand shock.xi While the fact that there was (and would be) a substantial supply component to the shock was recognised reasonably soon afterwards, it is probably fair to say that the decomposition was not well understood and the focus on demand attracted the main attention from the authorities.

The Treasury and the Reserve Bank have a long-established history of sharing information while ensuring they protect the Reserve Bank’s independent operation of monetary policy and the Treasury’s own role of providing independent fiscal and macroeconomic advice to the Government of the day. We think this is entirely appropriate, recognising that collaboration of this sort does not – and should not – blur respective accountabilities.

Nevertheless, some gaps in the Treasury and Reserve Bank coordination in an emergency were revealed, despite the fact that it was good by international standards. The pandemic experience has thus provided an opportunity to reflect on how those gaps arose and how they could be avoided in another crisis situation. At present, there is no commonly understood ‘playbook’ for how (and how much) to coordinate monetary and fiscal policy in future crisis scenarios (including varying pandemic scenarios), including which policies might have the advantage at which stage of the crisis. In addition, those involved need to have a good grasp of the kind of information which might be of value to the other organisation, without overstepping the bounds of what should or should not be disclosed. There may also have been occasions during the pandemic when information from other players (such as the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment and the Financial Markets Authority) could have been useful. These gaps in information sharing and coordination of policy could also have contributed to a ‘less than smooth’ pattern of macroeconomic stimulation and constraint over the period of the pandemic.

In summary, we think the ‘least regrets’ approach at the beginning of the pandemic was appropriate. Nevertheless, as the pandemic evolved all of the information and tools available to authorities were not used to achieve the right balance between avoiding deflation (and possible financial crisis) and economic depression in the short term and limiting the extent of the unavoidable price that is paid in terms of inflation, debt and lost productivity in the medium to long term.

6.3.3 The pandemic’s economic impacts put many households and businesses under great pressure, especially during lockdowns

The initial phase of COVID-19 left many businesses unable to operate. The incomes of millions of New Zealanders were thus at risk, creating potentially huge ripple effects that worsened the economic downturn created by the pandemic. However, the Government did provide assistance to lower-income New Zealanders in its March 2020 economic package and in Budgets 2020 and 2021, by means of either benefit increases or the Winter Energy Payments.

The Wage Subsidy Scheme (see spotlight in section 6.2.1.2) was devised to enable businesses to maintain levels of employment and worker attachment to roles, and to provide workers in permanent full-time or part-time roles with continued income. In addition, individuals who lost their employment (including self-employment) because of the pandemic could access the non-means tested COVID-19 Income Relief Payment.51 Despite the fact that not all income earners received the wage subsidy, these measures were well received and used. Over the five waves of the Wage Subsidy Scheme, 2,026,054 applications were approved (with 340,226 declined).52

Alternative mechanisms – such as delivering income support through the income tax system – might have offered some advantages (such as better targeting), but this approach would have been less effective in maintaining levels of employment and worker attachment to roles (one of the primary purposes of the Wage Subsidy Scheme).

While wage subsidy and other supports were available to help those in traditional employment, people in other situations struggled. For example, casual workers whose employers did not apply for the wage subsidy did not receive any wage subsidy payments.

Another group which experienced significant economic hardship during the pandemic was temporary visa-holders. This group included people on two-year work permits, international students and Recognised Seasonal Employer workers: when their employment ended, they were ineligible for most types of supportxii and were also significantly impacted.53 It was not until July 2020 – five months into the pandemic – that the Department of Internal Affairs and the Red Cross partnered to provide humanitarian relief to temporary visa-holders. This took the form of food supplies, housing assistance or support to return to their home country.

Through the public submissions process, we heard first-hand accounts of the pandemic’s economic impacts on many individuals, households and businesses:

“As an Immigration Officer, I lost my job as the borders were closed so the company that I was working for dropped down to skeletal staff as no one could come into the country.”

“My husband & I are produce growers for the local markets, by closing down the Farmers Market we now had no place to sell our produce which would not stop growing (leading to huge waste) and we had spent months of hard work preparing our crops to sell. This impacted our business financially and myself emotionally.”

“I have had a small business since 2007 and was unable to work due to the lockdowns for almost 7 months. This lost the business and my small team over $150k, which we have never been able to bounce back from, especially now as we head into a recession.”

“I was one of thousands of the uncounted. I lost income due to the lockdown as I was a casual worker. I didn’t receive the govt subsidy, I couldn’t apply for unemployment benefit as I was in a de facto relationship, so didn’t qualify there either.”

As we go on to discuss in the second part of this chapter, many social service providers we heard from confirmed that loss of incomes increased the material hardship many households experienced in the pandemic. Despite various new or increased social support initiatives (discussed later in this report), we heard of families with insufficient money for even the bare essentials like heating, internet, food, blankets, clothing, nappies, masks and cleaning supplies. And, as we also discuss later, the burden of these negative impacts was not shared equally across all New Zealanders. Inevitably, those people with existing disadvantages and vulnerabilities at the start of the pandemicxiii felt them the hardest. This made it imperative for the government pandemic response to consider equity effects and how they could be mitigated.

Many social service providers we heard from confirmed that loss of incomes increased the material hardship many households experienced in the pandemic.

6.3.3.1 Businesses experienced the pandemic differently according to their sector, size and location54

Many businesses told us that the Ministry of Health had little understanding of the practicalities of implementing many of the health orders in their workplaces. Businesses expressed frustration with the Government on various matters, including:

- The borders around Auckland (and sometimes inconsistent approaches to accessing the road corridor) made business operations around Northland extremely difficult.

- There was a sense that Wellington was disconnected from or lacked understanding of the impacts of various health measures on Auckland businesses.

- Many businesses felt that they had knowledge and expertise that could have helped Government, but they were not used – for example, employment lawyers and professional bodies who were not consulted over the Wage Subsidy Scheme, special COVID-19 leave and other matters that interacted with employment legislation.

- Complex and frequent legislative and regulatory changes made it difficult to understand and keep up with what was required. For example, we heard that after the COVID-19 Public Health Response (Maritime Border) Order 2020 came into force, ships’ pilots were initially required to wear full personal protective equipment (PPE) (including goggles) when transferring from one ship to another, often on ladders in pitching seas. This was both a health and safety issue for the pilots, and a legal quandary for their employers: they had to choose between observing health and safety obligations or maritime border orders.

- Businesses had access to data and networks that could have been very helpful to government but were not often accessed.

- There were complaints from businesses about the slowness to allow rapid antigen testing, and about the Ministry of Health objecting to the possibility of the private sector using saliva testing instead.

- Business associations considered the Government could have given them greater advance notice when communicating policy and other changes to businesses.

- Operating business policies relating to requiring workforce vaccination was a key issue for a number of businesses, and of course, for their employees. This is covered in Chapter 8 later in this report.

Exporters

Most visibly affected were those businesses which exported services and relied on an open border to access their markets; the regions they operated in were also hard-hit. Tourism and the international education sector – both high foreign exchange earners and large-scale employers – were the most obvious examples.

For other export sectors, the situation was more nuanced. Not all exporters were allowed to operate during lockdowns. The agricultural sector was one exception for several reasons: animal welfare, the continued health of agricultural production systems (for example, plant health), and the need for food security meant that many rural operations and related production simply had to continue. To allow this to happen, the Ministry for Primary Industries developed (in just two days) a set of rules which the agricultural sector had to comply with, and audited 8–9,000 businesses for compliance in the first two-and-a-half weeks – a considerable achievement. This exemplifies how a principle or desired outcome can be taken as a starting point, then a sector works out how to achieve it (in this case, how to reduce transmission risk) while keeping other things going as best as possible.

For the duration of the pandemic, many exporters were unable to visit overseas markets due to closed borders and disrupted air travel. Their concerns that this would result in a loss of customers was partly offset by New Zealand Trade and Enterprise scaling-up its overseas presence, thanks to $200 million funding from the Government to build its capacity in overseas markets.

Lockdown-related problems

Other issues affecting businesses related mostly to the impact of lockdowns. For example:

- The closure of butchers, restaurants and other hospitality venues during lockdown caused significant problems for pork producers while pork imports continued. Pigs were unable to be taken off farms for processing, which led to animal welfare risks due to continued breeding cycles and the number of pigs on-farm.

- The requirement for specialist food retailers (such as butchers) to remain closed during lockdown meant people purchased almost all their food through the main supermarket chains. This adversely affected those retailers: the Inquiry heard from a number of groups about the financial and mental health issues faced by small businesses. The closure of small retailers also had the effect of reinforcing the supermarket duopoly. We frequently heard complaints about the perceived unfairness of this situation, and the view that some small retailers providing essential supplies could have operated just as safely as supermarkets.

- Retail, hospitality and other businesses that relied on direct customer interaction were also adversely affected – not only by the lockdowns themselves, but by the shift to people working from home after lockdowns were lifted. From the start of 2020 until October 2022, there was a loss of consumer spending in the Auckland city centre of about $870 million – an average loss of $675,000 per business. Similar effects were felt in other city centres.

Often, large businesses were better able to absorb the shock than small businesses with low capital stocks as they had larger capital reserves to call on.

Some sectors – such as banking, financial services and technology – were well positioned to shift to digital or remote work. But other types of businesses that relied on physical, in-situ, or in-person work (such as construction or personal services) simply could not do so during the initial Alert Level 4 lockdown.

Working with Government

Many businesses and sector groups told us that officials making decisions about public health settings were initially unwilling to consider options which would have allowed non-essential industries to keep working safely – for example, road and bridge construction could have continued because workers generally keep a considerable distance apart anyway. Instead, several major construction projects came to a halt during the initial Level 4 lockdown, triggering force majeure provisions. These led to substantial commercial claims and losses, which are still being heard in the courts in 2024. It also led to key skilled workers leaving Aotearoa New Zealand, which in turn created further delays when those skills had to be re-introduced once construction work began again. We also heard that many of the smaller food providers and non-food manufacturers could also have operated safely, just as the essential food production sector managed to (and which was confirmed by audits such as the Ministry for Primary Industries’ compliance audit of agricultural producers mentioned earlier).

Businesses also told us that government agencies were sometimes inconsistent in their approach to public health threats. For example, government workers based at Auckland Airport were given PPE, but employees of Auckland Airport and other private businesses who worked in the same area could not obtain any.

Overall effects

Regardless of size, sector or location, the evidence shows New Zealand businesses were contending with a common set of challenges throughout the pandemic. In summary, they were:

- Worldwide, people’s behaviour changed significantly during and after the pandemic. These changes affected how people work, go to school, are entertained, how they shop and what they buy. For businesses, this has meant adjusting to different patterns of demand, providing goods and services in different ways, getting capital to invest in new activity and much more

- COVID-19 response measures profoundly impacted how people spent their money. The largest fall in spending occurred during the initial Level 4 lockdown in late March 2020, when spending dropped by nearly 55 percent.55 As a result of lower spending, people saved more during the national lockdowns.

- The pandemic caused business confidence and trading activity to decline on many occasions,56 reflecting the successive rounds of lockdowns.

- Businesses faced labour shortages due to travel restrictions and inflation, making it hard to expand their production to meet demand.

- Although businesses could pass on to customers some of their increased costs (which had risen due to higher input costs as a result of shortages of labour and materials), their profitability was nonetheless negatively impacted.

6.3.4 The pandemic created or exposed numerous workforce challenges, including shortages of workers in some sectors, a reliance on immigration, under-investment in human capital, inflexible legislation, pay inequities and more

At a strategic level, the pandemic presented several labour market challenges. These were seen in, but not limited to, the inability of several business sectors (such as healthcare and aged care) to secure the workers they needed. The pandemic also exposed some vulnerabilities. Lack of addressing them pre-pandemic meant that we were not as well placed in the pandemic as we could have been. Examples included:

- The degree of reliance on immigration to fill shortages of both skilled and unskilled workers.

- A lack of investment in building human capital, especially critical human capital.

- Questions about whether legislation was fit for purpose and agile.

- Health and safety issues.

- Inequitable work conditions, including pay.

- Rigid occupational regulation.

- The black/grey economy.

Some of these topics are covered in other parts of this report. In summary, the Government response only partially mitigated these issues businesses faced.

Generous government financial support, especially through the Wage Subsidy Scheme, ensured that the private sector workforce was largely sustained. The incomes of the public sector workforce were largely unaffected. Nevertheless, a range of influences – some reflecting pre-existing conditions – fueled shortages of both skilled workers (including university staff and specialised health workers) and less skilled workers (some types of farm workers, and hospitality staff) in some sectors. Those pre-existing conditions included workforce capacity and capability gaps, and insufficient income: some workers simply went to other countries where they could be paid more.

The wage subsidy ensured that most employment relationships were sustained (‘attachment effect’) during the pandemic, with some potential ‘long tail’ effects on productivity that are briefly covered in section 6.6. Of course, there were some closures and layoffs. For some people, the pre-existing benefit rules meant that they could not go on a benefit if others in their household were working. There were also regional, age, gender and sectoral differences in the take-up of the wage subsidy.

Immigration settings, and the slow response to the needs of business, contributed to workforce shortages though they were certainly not the only cause. Managed isolation and quarantine (MIQ) restrictions also had a negative impact on the health system, which is heavily reliant on the continued supply of international health workers of all different skill levels.

Even though the pandemic intensified global demand for international health workers – and Aotearoa New Zealand’s successful containment of COVID-19 may well have made it an even more attractive option – foreign health workers faced several challenges, including securing MIQ places. Other shortages were exposed as border restrictions were put in place (see Chapter 4 for more on the effects of border and quarantine measures on the workforce).

For employers and employees, the employment situation was stressful and hard to navigate. We were told about employers having difficulty finding the underlying legislation, regulations and guidance notes across websites; the introduction of new concepts that were untested by the courts and had to be applied in the new environment; and people finding it hard to quickly seek remedy or clarify the interpretation of law.

Another major issue for employers was the emotional, psychological and health impact COVID-19 had on their staff. Workers in essential industries often experienced stress, some lived in crowded households, and some were reluctant to have close contact with their families and friends – or, conversely, were shunned as possible vectors of infection. Absenteeism at work increased. A fuller account of these impacts can be found in the second half of this chapter.

6.3.5 The supply chain was disrupted by international and domestic developments during the pandemic, but the impacts have not yet been fully analysed; doing so is essential for improving the supply chain’s resilience in another such crisis

In general, Aotearoa New Zealand did not experience food shortages or lack essential goods. But supply chain problems nonetheless arose through a combination of global trends, domestic public health measures (such as the need for social distancing in ports and distribution centres) and ‘panic buying’ of some items such as toilet paper. The two major supermarket chains (Woolworths/Countdown and Foodstuffs) both experienced some product shortages.

There were initial fears that – because New Zealand was at the far end of international supply chains – some shipping companies might choose to drop it from their scheduled services. In the event, this particular risk did not eventuate. However, shipping was nonetheless disrupted throughout the pandemic, which affected export and import trade. Shipping reliability rates (the extent to which shipping lines met scheduled times) to New Zealand ports plummeted, falling from 80–100 percent in January 2020 to 0–20 percent a year later.57 This created uncertainty for importers about when expected freight was due to arrive, while exporters could not be confident of when they could deliver goods to overseas markets.

Shipping freight rates were also volatile. Global container shipping costs increased by approximately 500 percent during late 2020 and 2021 to a peak in October 2021 but had fallen to pre-pandemic levels by October 2023. Bulk shipping rates also increased sharply (again by approximately 500 percent between April 2020 and October 2021) before falling to pre-pandemic levels by January 2023.58 Air cargo freight rates increased too, but, despite general disruption to global aviation, the value of cargo imported through Auckland Airport continued to increase throughout the pandemic. This showed that demand for air cargo remained high and that, at least on the surface, the Government’s air cargo subsidies had some effect.59

While Aotearoa New Zealand lacks data measuring the impact of supply chain disruptions during the pandemic, we note that many other countries experienced slower supplier delivery times.60 Substantial increases in supply chain disruptions and backlogs were also reported: globally, supply chain disruptions (such as from shipping delays and stock shortages) grew from approximately 25 percent in 2019 to over 70 percent in 2020/21.61 New Zealand businesses reported similar problems.

In our discussions with businesses, they also identified several domestic sources of supply chain disruption. For example, the Auckland lockdowns restricted the availability of Auckland-manufactured goods (such as building products) elsewhere in the country, while there were also periodic shortages of freight capacity on the Cook Strait ferries. Some stakeholders also cited a lack of understanding among government officials about the interdependencies between internal supply chains – for example, between food exports and the local packaging supply sector, or food manufacturing and the waste recovery and recycling sector.

Combined with the broader impact of public health measures – such as the lack of any provision to allow ‘non-essential’ industries that could continue to function with a reasonable degree of safety to do so – these supply chain disruptions had considerable economic impacts. For example, the non-food manufacturing sector (which accounts for 69 percent of New Zealand’s manufacturing GDP) was unable to operate during the August 2021 lockdown: the effects were felt both by their downstream customers and by many export-oriented businesses that had spent years building up their international customer bases. Their inability to supply customers overseas led to the loss of significant current and future export markets.

From the evidence we have seen, the authorities have not yet comprehensively analysed or assessed the pandemic’s impacts on the supply chain. However, we are aware that the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment is leading work to implement the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework’s supply chains agreement. Through that agreement, countries commit to promoting regulatory transparency; identifying the supply chain stress points the COVID-19 pandemic exposed, and the critical sectors and goods affected; and coming up with practical solutions to the supply chain disruptions that remain in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. In our view, managing future risks to the supply chain and ensuring resilience is an important component of Aotearoa New Zealand’s preparedness for a future pandemic – a point we return to later in our lessons and recommendations.

x This is the Government’s debt, adjusted for its total cash or liquid assets.

xi A ‘demand shock’ refers to a downward adjustment to economic activity due to less spending by the government and/or private sector.

xii As part of the Community Wellbeing package in Budget 2020, the Government provided funding so foodbanks and community food services could support an estimated additional 500,000 individuals and families impacted by COVID-19 who were struggling to afford food. Access to these supports was not assessed on the basis of residency status. See endnote 53 for more details.

xiii The population groups that the Ministry of Social Development identified as being at higher risk of adverse social and psychosocial impacts in the pandemic were: older people, disabled people and people with long-term health conditions, lower income households, Māori communities, Pacific communities, children and young people with greater needs, young people (16 to 25 years), homeless, ethnic and migrant communities, the prison population and people on community-based sentences and orders, and women.