3.2 What happened I aha

3.2.1 The first national lockdown, March–May 2020

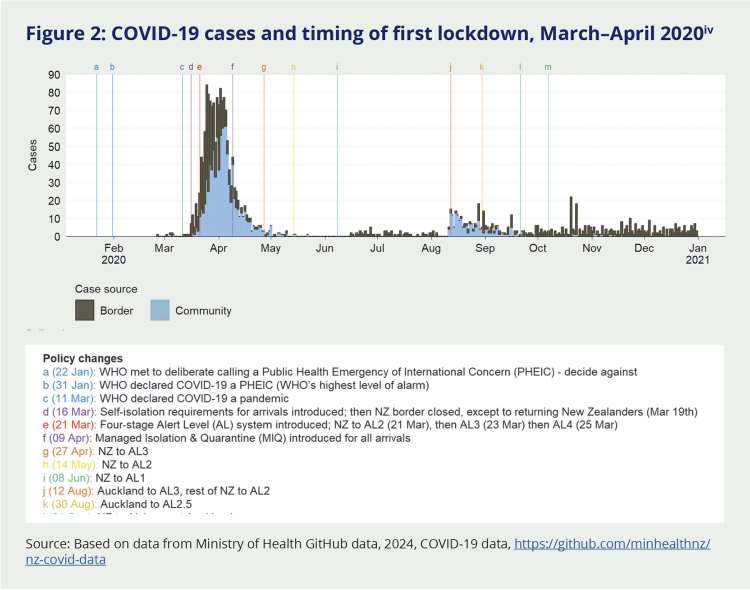

Aotearoa New Zealand spent seven weeks in Alert Level 3 and 4 lockdown between March and May 2020. The need for lockdown-like conditions was anticipated when Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern announced the Alert Level System on 21 March 2020, and from there things moved quickly. On 23 March 2020,5 the number of confirmed cases in New Zealand passed 100,6 and the Prime Minister announced that the country had moved to Alert Level 3, to be followed by Alert Level 4 in 48 hours.7 From this point, New Zealand was in ‘lockdown’.

This decision was informed by concurrent international experience (observing what was happening in countries that had acted swiftly or less boldly) and Ministry of Health officials’ assessment that it was highly likely community transmission was occurring in Aotearoa New Zealand. In making this decision, Cabinet considered the many potential implications of the restrictions, including wide-ranging economic impacts (and proposed mitigations), te Tiriti o Waitangi considerations, and the very significant social implications, especially for people who might be disproportionately impacted (including Māori, Pacific communities and older people).8

At Alert Level 4, everyone was instructed to stay at home in their household ‘bubble’ other than for essential personal movement. Gatherings were cancelled and public venues were closed, as were all businesses other than those recognised as essential services like supermarkets, pharmacies, healthcare clinics, petrol stations, and lifeline utilities. Educational facilities were all closed for in-person learning. ‘Safe’ recreational activity (walking, running, and cycling – but not swimming) was allowed in people’s local area, but any travel was severely limited, as were activities where there could be a higher risk of injury. Public facilities, including playgrounds, were closed. Aotearoa New Zealand remained at Alert Level 4 for almost five weeks.

“If community transmission takes off in New Zealand the number of cases will double every five days. If that happens unchecked, our health system will be inundated, and thousands of New Zealanders will die … Moving to Level 3, then 4, will place the most significant restrictions on our people in modern history but they are a necessary sacrifice to save lives.”9

Right Honourable Jacinda Ardern, 23 March 2020

3.2.1.1 Case numbers fell, enabling Aotearoa New Zealand to move down alert levels

For the first two weeks of the initial 2020 lockdown, case numbers continued to grow, and some people became very unwell from COVID-19. The first COVID-19-related death in Aotearoa New Zealand was recorded on 29 March 2020, a few days after the country entered Alert Level 4 or a ‘hard’ lockdown.10 By 5 April 2020, the total number of recorded cases was 1,000.11

However, from that peak, case numbers began to fall. This success is not attributable to the lockdown alone, but to the combination of measures that were being deployed in pursuit of the elimination strategy (namely, the evolving international border restrictions and increasing contact tracing and isolation of people infected with COVID-19). Undoubtedly, though, given the context and other available options, lockdown conditions were a key component in the success in eliminating transmission of the virus in Aotearoa New Zealand (for a more detailed discussion of the epidemiology, see Appendix B).

In the last week of April 2020, the whole country moved down to Alert Level 3 – a ‘softer’ version of lockdown, with less stringent conditions than Alert Level 4. Cabinet had previously agreed to specific factors that would guide decisions on moving between alert levels, a recognition of the difficult balancing of interests such decisions would demand. They would take account of health considerations (level of community transmission, testing and tracing capacity, adherence to border and managed isolation and quarantine (MIQ) measures, and health system capacity), social and economic factors, public attitudes and adherence, and ability to operationalise measures.12

The decision to move to Alert Level 3 was informed by the growing social, economic, fiscal and non-COVID-19 health costs of Alert Level 4 restrictions and the Director-General of Health’s advice that undetected community transmission was unlikely, that there was sufficient testing capacity and capability, strong processes for managing outbreaks in high-risk settings, robust border measures, and sufficient health system capacity.13

At Alert Level 3, people were still instructed to stay at home other than for essential personal movement but were allowed to expand their immediate bubble to connect with close family/whānau, bring in caregivers, or support isolated people (though this extended bubble had to remain exclusive). Schools (up to Year 10), kura and early learning centres re-opened but attendance was voluntary. Businesses were able to re-open, but only if they could operate without physical contact with customers. Workers who could operate from home were required to do so. Gatherings of up to 10 people were allowed, but only for weddings, funerals and tangihanga.14

Case numbers continued to fall, supported by the public’s high compliance with restrictions and the progress made in scaling up key public health systems (including testing, contact tracing and isolation). The first lockdown ended on 13 May 2020 when the whole country moved to Alert Level 2. (See Appendix B for a more detailed account of case numbers, hospitalisations and deaths at different stages of the response).

3.2.1.2 Most people complied with the first lockdown, there was a strong sense of solidarity, and agencies took a light-touch approach to enforcement

Despite the general uncertainty and lack of preparedness, high public compliance with the strict lockdown settings maximised the chances of rapidly stopping community transmission of COVID-19. People, systems and communities rose to the occasion, and many examples of innovation, collaboration and resilience helped to enable compliance with these challenging measures.

Social cohesion and trust in government stood out as a key enabler of an effective societal pandemic response.15 During COVID-19, high levels of social cohesion were shown to support greater social licence for action and effective community-led responses, and were associated with lower infection and death rates.16 According to various measures, levels of social cohesion and trust were relatively high in Aotearoa New Zealand prior to COVID-19.17 This strong base – mobilised in public appeals to the ‘team of 5 million’ to ‘Unite Against COVID-19’ – supported high compliance with lockdowns and other measures, at least in the early stages of the response.18 (See Chapter 2 for more on public information and official communications, including the Unite Against COVID-19 campaign.)

In keeping with the emphasis on solidarity and kindness in public communications, responsible agencies generally took a principles-based, ‘light touch’ approach to enforcing lockdown rules where possible (although the Inquiry was told by some people that they considered enforcement to be ‘harsh’). Police had significant enforcement powers, first under existing legislation and later under the COVID-19 Public Health Response Act 2020, but chose to use them sparingly, prosecuting only the most serious and persistent breaches. In the first week of the lockdown, they announced they would use a graduated model known as the ‘4 Es’ (engage, educate, encourage, enforce) to support compliance with lockdown rules. This approach drew on pre-existing Police principles of policing by consent and prioritised maintaining the trust and confidence of communities.19 The ‘4 Es’ became the basis of a wider All-of-Government Compliance Response, agreed between all major enforcement agencies in April 2020, to support a collaborative and consistent approach to compliance and enforcement for the COVID-19 response.20

Despite the predominant mood of public solidarity, and agencies’ trust-based approach to compliance, there were some early signs of disharmony about lockdown rules, along with some confusion and the perception of some mixed messages. For example, while the dominant messaging was to ‘be kind’, there was high public interest in perceived breaches of lockdown rules. A few days into Alert Level 4, on 29 March 2020, Police launched an online tool where people could report suspected rule violations. More than 80,000 reports were received over the next month; more than the total number of 111 calls in the same period.21 (We return to the topic of social cohesion in Chapter 8.)

3.2.1.3 Iwi and Māori, and many communities, provided significant leadership and support

Iwi and Māori and many communities of different kinds – neighbourhoods, cultural groups, online groups, non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and community organisations, religious institutions, families, whānau and aiga – stepped up during the first Alert Level 3 and 4 lockdowns to provide essential local leadership, support each other and address local needs.

There are many well-documented examples of community groups taking charge of the response on the ground. Sometimes in partnership with government, and sometimes independently, they sourced kai, medicine, resources and other essential items, and distributed them to those who needed them. Recognising people needed more than food and medicine, they provided other support too, ranging from making direct donations, offering transport to essential destinations, enabling technology and data connections, and linking individuals, households, families and whānau with government support (see Chapter 6 for more on the social response). Existing hubs such as marae and places of worship (and the relationships and community knowledge that came with them) meant support could be tailored to individual needs. Community organisations, both formal and informal, were also well placed to meet unseen needs such as for fellowship and connection. Many people trusted community organisations to sort, curate, and act as conduits for reliable information. New grassroot groupings, such as community social media groups, were created that enabled people to check on and help each other. Some organisations ran phone trees to check on older people and other potentially vulnerable groups.

Within ethnic and migrant communities, there was strong guidance and engagement from many community leaders. Communication across many languages was particularly important. Within Pacific and Māori communities, clusters of churches, marae, sports clubs, health centres and community support groups provided networks of support and information, connecting people to resources and services and advocating for those who were more vulnerable. Several community organisations networked their personal capabilities to help support the broader pandemic response, such as using their personal 3D printers to make face shields for essential workers.

Pacific churches generally played a strong leadership role in addressing specific challenges faced by their communities. Physical distancing is difficult when families live in multigenerational and often crowded homes. Pacific households have the lowest level of home internet access compared with other New Zealand ethnicities and are over-represented in low-income occupations (such as retail, food supply, and health, disability and aged care), many of which were classified as essential during the pandemic. Churches used their existing relationships and built new ones to ensure the needs of their communities were met. They linked in closely with Government to understand what was happening, and what response was needed from their communities.22

In combination with the work of social sector agencies (covered in section 3.2.1.7), these multi-faceted community efforts undoubtedly alleviated many of the potential negative impacts of lockdowns on individuals and groups.

Iwi and Māori leadership

Iwi and Māori played a significant leadership role in mobilising their communities and mitigating the negative impacts of lockdown. Early in the pandemic, iwi, hapū and marae across the motu developed plans that adapted tikanga and kawa to the challenges presented by not being able to interact in person. This included hapū and marae committees temporarily closing marae, restricting papakāinga access, and developing new protocols for tangihanga and tupāpaku under lockdown conditions, despite significant personal, cultural and spiritual impacts.23

Iwi and Māori also worked closely with law enforcement in response to COVID-19 to encourage compliance. Māori leaders we engaged with told us that iwi and Māori ‘policed ourselves’ to follow the rules, and this appears to be borne out by the data: while Māori unfortunately are generally over-represented in Police enforcement action, and this remained the case during the pandemic, this happened at significantly lower levels than usual.

Spotlight: Te Tiriti o Waitangi partnership in action Te whakatinanatanga o te hononga Tiriti

Iwi and Māori in Tairāwhiti, Bay of Plenty, Taranaki and Te Tai Tokerau stood up checkpoints to limit the movement of people and control the spread of COVID-19, just as they had done a century before to control the 1918 flu.

Almost 50 roadside checkpoints were established, resourced and led by iwi and Māori, staffed by volunteers, and often operated in partnership with NZ Police. In addition to protecting local residents (both Māori and non-Māori), such checkpoints were valuable for disseminating information and contributed to a sense of trust between Police, Māori, and the wider community, although some parts of the population found them challenging.24

Coming out of the initial lockdowns, iwi and hapū representatives have spoken publicly about the positive impact of the partnership between Māori and Police on iwi checkpoints.

Tina Ngata (Ngāti Porou) noted that:

“like all relationships with the Crown, it has not been without challenges, and it is still a work in progress, but in supporting our protection of our communities, New Zealand Police have stepped into their partnership [with Māori] responsibilities in their fullest sense.” 25

Rahui Papa (Waikato-Tainui) spoke of how strengthened relationships with Police had seen issues:

“resolved quickly and efficiently, with cultural considerations at the forefront. The place of tikanga and best practice in these relationships is an example, not just for a pandemic context, but further into the future.” 26

Police representatives made similarly positive comments. Eastern Bay of Plenty area commander Stuart Nightingale said that the community safety zones provided additional protection to the remote and vulnerable community of Te Whānau-ā-Apanui and had:

“clearly achieved what they set out to do. Community policing means working in partnership and building solutions to problems in conjunction with the communities we serve.” 27

Other community leaders also expressed gratitude to iwi for the checkpoints. South Taranaki Mayor Phil Nixon said:

“I really support what they’re wanting to do to protect our community. They’re going to great lengths to look after us.” 28

On the other hand, our Inquiry heard from some public submitters who found the roadblocks challenging.

Shortly after the initial lockdown, the COVID-19 Public Health Response Bill was introduced to Parliament. The original version proposed to make it unlawful for anyone other than Police to run roadblocks, which some felt was ‘tone deaf’ to the rights of iwi to exercise tino rangatiratanga in their own rohe.29

3.2.1.4 An essential services category was established to ensure access to critical goods and services while limiting people’s movements

Like most countries, Aotearoa New Zealand established an essential services category during COVID-19 lockdowns to ensure continued access to food, critical goods, and lifesaving and preserving services. This largely determined who could leave the house, go to work, and travel locally at Alert Level 4.

Existing legislation and international guidance provided a starting point for the definition of ‘essential’ services.30 However, no detailed work had been done in Aotearoa New Zealand pre-2020 to define the scope of essential services, businesses and workers in a pandemic context.

The Alert Level System was announced on 21 March 2020. The strict limitations envisaged at Alert Level 4 meant that a formal definition of essential services would immediately be required if the country moved to that level. As with many other aspects of the response at this time, advice was being developed at pace and without time to refine and test definitions and approaches. An initial list of essential services was appended to Cabinet Papers recommending the move into lockdown (Alert Levels 3 and 4), with an understanding that the list would be continuously reviewed and adjusted.

Cabinet adopted four principles to guide this process: prioritising public health and allowing the Government to scale-up the response, while at the same time ensuring the necessities of life and maintaining public health and safety.31 These reflected decision-makers’ primary focus at the time on reducing community transmission of the virus (discussed in Chapter 2). Notable criticisms of the essential services scheme include that it struggled to keep up with the (often changing) needs of business and the community, and was sometimes applied in what appeared to some to be an arbitrary fashion (for example, supermarkets could open but butchers could not).

As the country moved into Alert Level 4 late on 25 March 2020, the Director-General of Health used existing powersii to close all premises except for ‘businesses that are essential to the provisions of the necessities of life and those businesses that support them’.32 The Ministry of Business, Innovation, and Employment (MBIE) was tasked with administering and regularly updating a definitive list of essential services. Despite the flexibility built into this approach, some essential services, industries and oversight mechanisms that should have been operational were initially excluded (e.g. victim support and court workers), and it wasn’t always straightforward to address some of these omissions. In addition, as time went on, some things that were not essential in the short term (like various maintenance activities) became essential. Officials we engaged with told us their advice to Cabinet at the time highlighted that the essential services approach was unlikely to be sustainable over an extended time frame and that a different approach would be needed at lower alert levels.

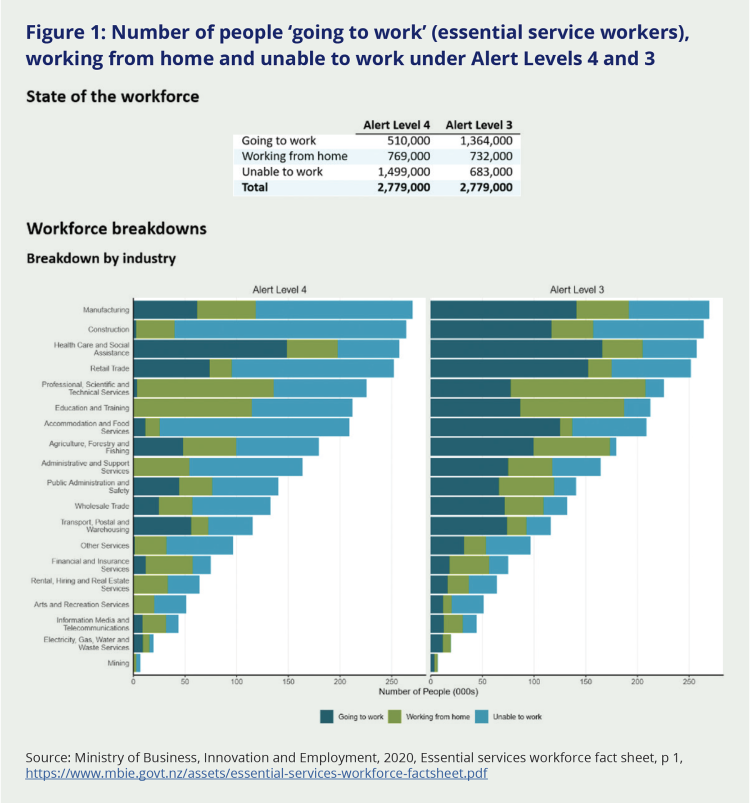

Approximately half a million people regularly left home to go to work during Alert Level 4.33

Formal use of the essential services category to require certain types of premises to close ended when the country moved to Alert Level 3 on 27 April 2020.34 It was replaced by a requirement for businesses that re-opened to meet specific, strict requirements for physical distancing, contact tracing, and contactless delivery. Businesses accessed by the public (retail, hospitality) could open but only for online or phone purchases, and contactless delivery or collection. This reflected a shift from essentiality to safety. Alert Level 3 settings also required anyone who could work from home to continue to do so.

Around 1.3 million people regularly left home to work during Alert Level 3, about 49 percent of the workforce.35

Figure 1: Number of people ‘going to work’ (essential service workers), working from home and unable to work under Alert Levels 4 and 3

Source: Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment, 2020, Essential services workforce fact sheet, p 1, https://www.mbie.govt.nz/assets/essential-services-workforce-factsheet.pdf

3.2.1.5 Many businesses, households, community groups and individuals switched to working, learning and socialising online

Workers who were not employed by essential services (and some who were, whose jobs could be done remotely) switched to working from home during lockdown. Around Aotearoa New Zealand and the world, businesses, schools and community organisations rapidly switched to remote ways of working and connecting. This was critical to the successful use of lockdowns: the World Health Organization’s independent panel on pandemic preparedness later found that good digital access was one of three necessary prerequisites for effective stay-at-home orders (along with adequate household income and a high level of trust in government).36

The fact that broadband infrastructure had been rolled out to most of the country in recent years proved vital to allow most people in Aotearoa New Zealand to work, learn, socialise, and keep entertained online during lockdown. However, there were some key gaps in coverage, especially in rural areas.37 Beyond infrastructure, there were other barriers to digital access for some, including affordability of devices and connections, and lack of skills or knowledge. As one stakeholder put it to us:

“If you’re rural you don’t have the connection. If you’re poor, you don’t have the devices. If you’re old, you don’t know how to use the device.”

Those fitting into one or more of these categories were a minority of the total population, but a significant one.

Some sectors and workforces were better prepared for (and better suited to) remote work than others. This reflected a wide variety of factors including pre-existing digital access, varying levels of skills and investment in IT capability, working from home conditions and the nature of the work (if it was desk-based or face-to-face, for example).

COVID-19 provided the catalyst for public sector agencies and workforces to switch to remote working. Many thousands were sent home to work and continued to deliver essential public services in a completely new way. For example, the justice system was able to build on the limited audio-visual links already available in some courts to enable remote participation on a much wider basis. In some cases, as with the Ministry of Social Development, this involved a near-total overhaul of their operating model.

3.2.1.6 Schools, kura, early learning centres and tertiary education providers were closed for in-person learning, and switched to remote learning where possible

Schools, kura, early learning centres and tertiary institutions were closed for in-person learning from 24 March 2020 to 28 April 2020.iii Under Alert Level 3, education providers could be open for children up to Year 10 for families that needed them. Their closure for most in-person learning required educational settings to rapidly switch to deliver remote (and later hybrid) learning.

Cabinet authorised $87.7 million to support the switch to remote learning. This sum was to cover connecting the homes of 40,000 eligible learners to the internet, providing schools with 49,000 fit-for-education devices for students, producing English and Māori medium educational television broadcasts, and distributing printed learning resource packs to most schools and early learning centres.38

The Government also funded digital access for some tertiary students, increased the course-related costs component of student loans, and provided $56.8 million through the COVID-19 Response and Recovery Fund (see Chapter 6 for more on this fund) in recognition of the loss of international students.39 This was in addition to the decision to continue to fund tertiary education organisations at the levels set out in their investment plans for on-Plan funds, irrespective of any potential reduction in student numbers (a transfer of the Tertiary Education Commission’s grants obligations to 2020 of $1.1 billion).40

Budget 2020 also included a $50 million Urgent Response Fund to help early learning services, schools and kura to improve attendance and manage any learning, social, emotional, mental or other wellbeing needs related to the COVID-19 lockdown.41 This was distributed using the Equity Index to target schools and communities in greatest need. In total, a reported $199 million was invested in new education initiatives in 2020, most in direct response to COVID-19.42

During Alert Levels 3 and 4, most schools explicitly prioritised student wellbeing over academic learning, recognising that they could not expect a ‘normal’ workload under extraordinary circumstances. Despite this, many students and teachers were worried about falling behind.

Delivering remote learning proved challenging at all levels. It was not practical or appropriate to fully deliver the early childhood curriculum remotely, given the age of these children and the fact that most of their learning is play-based. Nevertheless, most early learning services provided some form of remote teaching and learning, focused on identifying and building on learning opportunities at home.43 Many teachers and educators worked hard to rapidly upskill and adapt to deliver the primary and secondary school curricula remotely, though the experience of this was variable.44 The tertiary sector’s move online was also patchy and depended on individual institution size and capability. Whilst some pivoted promptly and efficiently, smaller and regional institutions took longer. Many tertiary institutions opted to deliver remotely beyond May 2020, given the volatile environment and repeated alert level changes in Auckland. For staff at all levels, the additional workload associated with the shift was considerable.

Tertiary education providers could return to limited in-person learning at their discretion from 28 April 2020, at Alert Level 3, although the Ministry of Education advised that staff and students should continue working or learning from home where possible.45 Most providers remained online or delivered hybrid options. From 14 May 2020, schools, kura and early learning centres began a phased return to in-person learning, ahead of the move to Alert Level 2 on 18 May 2020.46 Strict precautions would be in place, including designated bubbles, social distancing and hygiene routines. Some disruptions continued even once schools reopened, when close contacts were required to isolate, or schools that had been sites of transmission were required to close.

Spotlight: Life in lockdown Te ao o te noho rāhui

In some ways, lockdown might be seen as putting everyone in ‘the same boat’. But the reality was that the experience across the lockdowns varied greatly depending on individual circumstances, temperament, family situation, income, safety and stage of life.

Snippets from our public submissions give a flavour of the myriad experiences, positive and negative.

“We took long walks [with] the pram to look at the neighbourhood. We watched the forklift unloading groceries outside the supermarket. And we set our daily routines around the 1pm update, with the sound of voices lulling our toddler to sleep on the sofa. We look back really fondly on these times; they were happy days for our family.”

“I loved how quiet it was. I could hear the birds and nature. Walk in the middle of the road on quiet streets and experience it differently. […] It was also a really nice opportunity to enjoy recreational activities/hobbies again and felt like I was living again, and not living to work.”

“I felt immense pressure as a mum to deliver/be present with work, as well as present for my son’s learning and general entertainment/parenting.”

“The 108 day Auckland lockdown began to take a toll on my mental health with feelings of hopelessness and despondency, lack of energy and overall depression.”

“[B]eing confined to your property all day and night was quite draining on my mental health. [S]omething I didn’t realise would be the case until we were in the situation. Living with 4 other adults in a flatting situation at the time. [We f]ound that we all would drink alcohol each evening out of boredom and mental stress from being confined to our property and not having freedom to do what we wanted.”

“It was tough. We have 3 young children at primary school level [and] trying to maintain their schooling online plus both parents working full time, it was a struggle to find space to all work together. In addition, we had 4 pensioners in our bubble. Lockdown in Auckland was overall challenging. Sharing space and devices was also a challenge.”

3.2.1.7 The social sector stepped up

In the social sector, the COVID-19 response was a step-change in the way government worked. The sector’s initial response to the lockdowns was characterised by high agility, flexibility and collaboration between government, iwi, and community partners together with an immediate injection of (mostly time-limited) funding. As well, there was a strong focus on outcomes.47 Providers were empowered to tailor their services to the needs and aspirations of the communities they were working with, and commissioning agencies relaxed requirements for outputs and reporting. A range of funding responses was put in place in the early phase of the pandemic, including specific funding tagged for disabled people, family violence and sexual violence, Māori, Pacific people and community solutions.48

More so than usual, government agencies operated a ‘no wrong door’ policy for those seeking support and worked closely with community groups and social service providers to ensure that families in need were able to access what they required, including food grants online, food parcels delivered, housing needs met urgently, and support to access household goods, clothes and appliances.

Service providers – which included NGOs, community groups, iwi and Māori organisations, and volunteers, as described in section 3.2.1.3 – often went above and beyond during this period. Many delivered services without contracts or funding, using their own resources, until government systems caught up. For more detail on the social and community sector response and impacts, see Chapter 6.

3.2.1.8 Immediate housing support was provided to those who were sleeping rough or living in insecure accommodation

The defining characteristic of lockdown was the requirement for people to stay at home. There were many groups for whom this was challenging or dangerous – among them people at risk of family or sexual violence, people living in cramped or overcrowded housing, medically frail or very elderly people who lived alone, and so-called ‘marginalised’ groups including gang members and people with addictions. Some of the most immediately vulnerable under ‘stay at home’ conditions were those who had no home at which to stay – people who were sleeping rough, couch-surfing, living in cars, or in highly unstable and unsuitable accommodation.

Ministers and officials understood that the transient movement of people living in insecure housing risked undermining the effectiveness of lockdowns as a tool to suppress and eliminate COVID-19, and that there had been little to no pandemic preparation in the housing and accommodation sector.49 In response, central government agencies worked quickly with community housing providers, social services, iwi and other Māori organisations, and local government to provide temporary and emergency housing support for people who were in insecure housing or rough sleeping. This was enabled by direct, fast communication, the swift adoption of permissive ‘high trust’ contracting models, and ample and immediate funding. In March 2020, Government instituted an immediate freeze on residential rent increases, and introduced new protections against the termination of tenancies.50

3.2.1.9 The first lockdown ended on 14 May 2020

On 14 May 2020, Aotearoa New Zealand moved to Alert Level 2. This marked the end of the first national lockdown, though significant restrictions were still in place. Cabinet delayed allowing social gatherings in public or private venues of more than 10 people, with a view to increasing this limit over time, and it delayed opening bars and clubs for an additional week. People were now permitted to connect with friends and family, go shopping or travel domestically – providing they followed public health guidance, including keeping physical distancing of 2 metres when out in public, and 1 metre in controlled environments like workplaces. Schools and educational facilities re-opened for in-person learning, with strict hygiene measures. Businesses could open to the public, including hospitality businesses, and record-keeping was required to allow contact tracing. Gatherings like weddings, funerals and tangihanga remained limited to 10 people. Masks were required on public transport. Those who could were still encouraged to work from home.51

Case numbers continued to fall at Level 2 and by 8 June 2020 when Cabinet met, there were no active community cases left. The country moved to Alert Level 1 on 9 June 2020 based on the high confidence that COVID-19 had been eliminated from Aotearoa New Zealand.52

Figure 2: COVID-19 cases and timing of first lockdown, March–April 2020iv

Source: Based on data from Ministry of Health GitHub data, 2024, COVID-19 data, https://github.com/minhealthnz/nz-covid-data

3.2.2 Brief Level 3 lockdowns in Auckland in late 2020 and early 2021

3.2.2.1 Auckland spent two and a half weeks back in Level 3 lockdown in August 2020

On 11 August 2020, after 102 days without community transmission, four people tested positive for COVID-19 in Auckland. Ministers with power to act decided to take a precautionary approach, and – in addition to contact tracing and stepped-up testing – moved Auckland into an Alert Level 3 lockdown, and the rest of the country into Alert Level 2, from midday on 12 August 2020.53 This was the first use of a regional lockdown.

For two and a half weeks, schools and early learning centres closed again except for those who ‘need to attend’ – mainly the children of essential workers. Others returned to online learning. Those who could do so went back to working from home.

On 30 August 2020, Auckland moved into a newly-created ‘Alert Level 2.5’. This was based on advice that, while the number of confirmed cases was increasing, the cluster was under control. Decision-makers were also conscious of the costly nature, both economically and socially, of holding Auckland at higher alert levels, the challenges inherent in implementing regional boundaries, and that Pacific and Māori communities were disproportionately affected by this outbreak.

While this decision ended the first regional lockdown, the new settings were more restrictive than the original Alert Level 2. Social gatherings (including weddings) were limited to 10 people, except for funerals and tangihanga, which were allowed up to 50 people in attendance. Hospitality businesses could not serve groups larger than 10, and masks were mandatory on all public transport in Auckland.54 Aucklanders were also asked, but not required to, comply with Level 2.5 settings wherever they went (including outside of Auckland), even though the rest of the country was at Alert Level 2.55 This temporary ‘half step’ was in place for three weeks and was not used again in the pandemic. By 8 October 2020, the whole country was back at Alert Level 1.56

3.2.2.2 Auckland moved in and out of Level 3 lockdown several times in early 2021

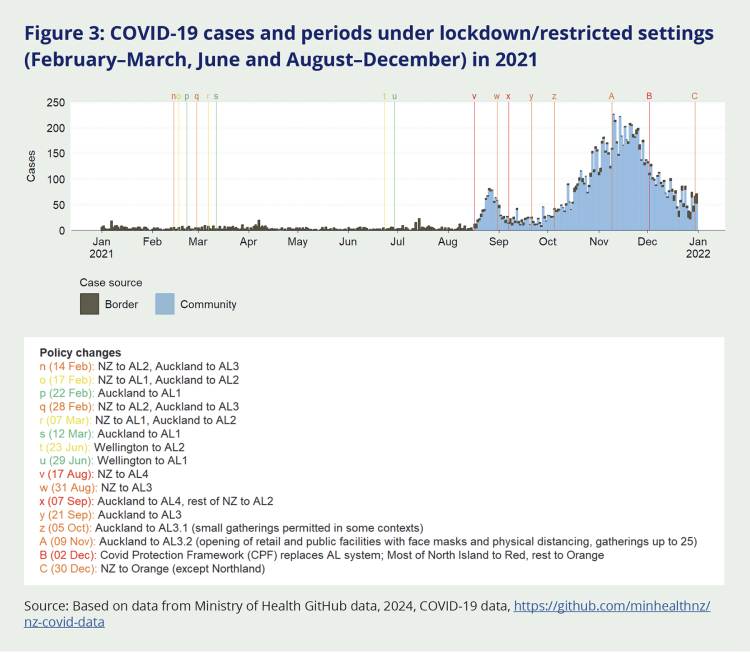

For a few weeks in February and March 2021, Auckland again moved in and out of Alert Level 3 lockdown several times, after more community transmission was detected.57 At this time, the total time spent in Level 3 lockdown was relatively brief – three days initially, and later one week – but it came at a disruptive time at the beginning of the school year. In June 2021, Wellington spent nearly a week at Alert Level 2 after a visitor from Australia tested positive following a short but busy weekend in the city.58 Aside from these short-lived regional disruptions, 2021 saw Aotearoa New Zealand remaining largely out of lockdown until the arrival of the Delta variant in August.

Figure 3: COVID-19 cases and periods under lockdown/restricted settings (February–March, June and August–December) in 2021

Source: Based on data from Ministry of Health GitHub data, 2024, COVID-19 data, https://github.com/minhealthnz/nz-covid-data

3.2.3 Delta lockdowns in late 2021

3.2.3.1 The entire country spent three weeks back in lockdown in August and September 2021

In 2020 and early 2021, lockdowns had proved to be an effective tool for achieving and maintaining New Zealand’s elimination strategy. Their effectiveness had derived from high levels of trust and social cohesion, strong support from communities, social and economic supports, and clear communication. As the use of lockdowns continued in 2021, decision-makers had to make increasingly challenging decisions. These involved weighing up a range of competing considerations – social and economic, as well as public health – which would have different impacts across population groups.

This phase of the lockdowns began after the World Health Organization indicated in June 2021 that the Delta variant was becoming the dominant strain globally. Delta was substantially more infectious than previous variants, making it harder to contain. It also caused more serious clinical illness.59

On 17 August 2021, a community case of COVID-19 was detected in Auckland. Officials assumed (correctly) that the case was the highly transmissible and more virulent Delta variant. The sick person had been active in the Auckland and Coromandel regions, and it was considered likely that the virus was already circulating elsewhere, so the Prime Minister announced an imminent Level 4 lockdown for the whole country. While the initial indication was that this would be another short-lived lockdown, the country remained in Level 4 lockdown for the next two weeks, and Auckland for much longer.

For the second half of August 2021, New Zealanders returned to settings and experiences that were largely familiar from the first Level 4 lockdown. This recent experience meant many people and organisations were better placed to respond with systems, processes, policies and technology already in place to manage in lockdown. The essential worker category was revived, online learning resumed, those who could worked from home, and community organisations again stepped up. Schools, kura, early learning centres and tertiary education providers returned to remote and online learning, and for the first time, the Ministry of Education distributed specific learning resources targeted at learners with sensory needs.

After two weeks, all regions except Northland and Auckland moved down to Alert Level 3, with Northland following a few days later. On 7 September 2021, all regions except Auckland finally moved out of lockdown to a strengthened Alert Level 2 (in which mask wearing was required in most public areas and permitted gathering sizes were reduced – see Chapter 8 for more on compulsory mask wearing).60 While some Delta cases were reported outside of Auckland, the combination of contact tracing and other public health measures was effective in these regions and community transmission did not take hold.

Auckland, however, remained at Alert Level 4.61 While Northland was theoretically at the strengthened Level 2 from 7 September 2021, the ongoing lockdown in Auckland meant it was effectively cut off from the rest of Aotearoa New Zealand (see also section 3.2.3.3). The Auckland lockdown continued to be extended, although it was stepped back down to Level 3 from 22 September 2021.62

3.2.3.2 The Delta lockdowns were much longer for Auckland (and some other regions)

By 4 October 2021, Auckland had spent 49 consecutive days in either Alert Levels 3 or 4. The public health risk remained, but ministers and officials were aware that there was ‘eroding social licence for heightened restrictions amongst compliant parts of the Auckland population’.63 Increasing vaccination rates were added as a further factor in Cabinet decision-making. Cabinet decided the country would transition away from the Alert Level System to the new COVID-19 Protection Framework, which would allow them to retire use of lockdowns as vaccinations provided an additional tool in the control of COVID-19.64 While the intention just one week previously had been to still control the Delta outbreak and ‘get back to zero cases in Auckland’,65 officials now recommended a ‘phased approach to step down restrictions over time as part of a gradual transition to the new “traffic light” framework’.66 This is what happened in practice, as cases in Auckland continued to rise while the costs of a prolonged lockdown accumulated.

By mid-October 2021 it was evident the Delta outbreak would not be easily eliminated. Focus shifted to maximising vaccine uptake in order to allow restrictions to be loosened – including a staged re-opening of Auckland schools.67 Health officials had previously advised that the transition to the new ‘traffic light’ system could occur once 90 percent of the eligible population had been vaccinated68 and the Prime Minister now presented this as the target that would allow Auckland to move out of lockdown.69 But despite significant efforts in the following weeks, vaccination levels continued to be substantially lower in Māori and Pacific communities70 and were not projected to reach 90 percent in Auckland District Health Board (DHB) areas until mid-December.71

When elimination was no longer possible, the justification for lockdowns shifted to protecting people (particularly vulnerable groups) from the severe impacts of COVID-19 infection, but this shift was not well-communicated to the public (as discussed in Chapter 2). Official documents from this period illustrate the challenging situation in which the Government found itself. On one hand, there was clear recognition of ‘eroding social licence’ among the Auckland population ‘who [have] endured a significant time at heightened Alert Levels’,72 coupled with ongoing economic and social impacts for businesses and families. Advice highlights the ongoing and increasing challenges related to financial support and economic, social and wellbeing impacts. General fatigue amongst the public was increasing and willingness to comply with some public health measures was reportedly reducing.73

On the other hand, officials were also acutely aware of the risks of removing restrictions while vaccination levels remained low in vulnerable population groups. The specific demographics of Auckland were relevant here, with recognition that South Auckland communities in particular ‘feature[d] a younger age structure, lower rates of vaccination and [were] likely to be at greater risk of hospitalisation’.74

In seeking to balance these concerns, officials developed proposals to modestly relax Alert Level 3 settings in Auckland in a staged manner. From 5 October 2021, Auckland was placed at Alert Level ‘3.1’ which permitted small gatherings in some contexts.75 A subsequent move to ‘Level 3.2’ on 9 November 2021 allowed the opening of some public facilities (including libraries and museums) with use of facemasks and physical distancing, and gatherings of up to 25 people.

Level 3.3 was never activated, because on 2 December 2021, Cabinet adopted the ‘minimisation and protection’ approach and Aotearoa New Zealand moved to the ‘traffic light’ system to manage the COVID-19 response. Auckland was put at the ‘Red’ level, along with several other regions that were considered to be at greater risk, either because of low vaccination rates or because they were popular holiday destinations.

At the ‘Red’ traffic light level, Auckland was technically out of ‘lockdown’, although some significant restrictions remained in place, and schools and early learning centres did not completely re-open for in-person learning until February 2022.

In total, Auckland spent more than six months at Alert Level 3 or 4, compared to 74 days for most of the rest of the country.

There was widespread criticism in our public submissions of the duration of the Auckland lockdown. People spoke about hardships they faced during this time, and about the additional alienation and burden they felt was carried by those in Auckland. We heard this may have had a particular impact on older people, as well as children and young people.

“Children being locked out of school, even for a short period, disrupts their relationships, a deeply distressing and potentially damaging thing for children approaching and in their teens.”

Public submission to the Inquiry

We also held direct engagements with bereaved families who were unable to be with sick or dying loved ones or attend their funerals due to the Auckland lockdown and heard of the level of trauma and distress they experienced. For some, these issues impacted on their trust in government, and their willingness to follow the rules.

Alongside this, the Government was also criticised for having transitioned to the new ‘traffic light’ system before the 90 percent vaccination goal had been reached. In the Haumaru report,76 released in late 2021, the Waitangi Tribunal found the Crown had breached te Tiriti o Waitangi principles in its decision to transition to the COVID-19 Protection Framework without meeting the original vaccination threshold. This decision was regarded as putting Māori at disproportionate risk of Delta infection compared with other population groups, given their lower vaccination coverage at the time of the transition. The Tribunal also noted that this decision was made despite the strong opposition of Māori health experts and iwi leaders.

With the ending of the Auckland lockdown, Māori health providers were under pressure to vaccinate their communities as quickly as possible in order to protect them from the health consequences of COVID-19 infection. The Tribunal found that this undermined their ability to ensure equitable care for Māori.77

We will return to what can be learned for the future from the intensity and length of the Delta lockdown in the ‘Looking Forward’ part of our report.

3.2.3.3 The boundary between Auckland and the rest of the country presented challenges

Regional boundaries, while valuable, were hard to implement – particularly at short notice and with no prior preparation across the system. These timing and preparedness issues caused many challenges for communities, businesses, workers and enforcement.

Implementing a regional boundary around Auckland was extremely challenging – particularly when done at such short notice – and those responsible worked hard to understand and balance the many practical issues this created for those on either side of the boundary line. We heard that policies relating to the boundary were not always based on local advice, and while some challenges were unavoidable, in other cases local input would have helped improve outcomes. Some communities were cut off from essential supplies (such as being able to access their normal pharmacy and medications) and checkpoints were sometimes in impractical locations (some lacked enough space for trucks to queue and had no amenities for checkpoint staff). These issues meant that boundaries were often changing in an attempt to resolve them.

Enforcement of boundaries also proved difficult with thousands of cars crossing the boundary every day, most of them for legitimate, necessary and permitted reasons.78 People crossing the regional boundaries in the last quarter of 2021 were also required to provide evidence of a COVID-19 saliva test within the last 7 days,79 which added further stress at the checkpoints, and for those wishing to cross. This requirement was introduced on the advice of Ministry of Health officials80 to mitigate the risk that essential workers might unknowingly transmit the virus across boundaries (for more on compulsory testing, see Chapter 8).

There were also unique pressures for Northland from the regional boundaries which saw them cut off from the rest of the country, apart from limited channels through Auckland. Businesses in Northland effectively became stranded from the rest of Aotearoa New Zealand, while other businesses throughout New Zealand (for example, the construction sector) were impacted by reductions in supplies of goods and services. We heard from some in Northland that they felt forgotten or overlooked and ‘lumped into Auckland’s mess rather than being treated as our own region’.

Spotlight: Beginnings and endings in lockdown Te tīmatanga me te otinga i te noho rāhui

Welcoming a new baby and farewelling a loved one are two of the most profoundly significant events in many people’s lives. They are also events that can rarely be planned or controlled. While most aspects of daily life ground to a halt during lockdown, babies continued to be born, and people continued to die – some from the virus itself.

But the support available to people going through these major life events, and the conditions in which they did so, changed dramatically. These were some of the most challenging and controversial aspects of the lockdowns and featured strongly in our public submissions.

Giving birth

Some submitters described the anxieties of expectant parents facing the prospect of giving birth without their partners or support people, or being unable to access the usual checkups during the perinatal period (pregnancy and the first year after birth). Others described difficulties finding a midwife, felt inadequately supported through post-natal depression or a traumatic birth, or had to stop IVF and other time-critical fertility treatments.

While some had positive experiences of giving birth during lockdown and expressed gratitude for a safe, COVID-19-free birthing environment and extra time together as a family, others relayed traumatic experiences. One submission (which we feel merits quotation at length) evoked the fear, grief and stress experienced by many birthing parents:

“I birthed my fourth child three days into the March 2020 lockdown. I was still in theatre getting stitched up when my husband was asked to leave the hospital, even though he posed zero risk to the staff or myself. I was in shock from an attempted vaginal birth and then [being] rushed through to theatre for an emergency caesarean. I nearly lost my baby and was at high risk of something going wrong and I needed support. I was drugged up and I didn’t feel safe to be left alone. I could not think straight, and I was scared. I spent four nights in hospital, unable to see my husband or three other children who had never really spent a night away from me. I couldn’t walk and had nerve damage from my epidural. I could barely move so co-slept with my newborn in a hospital bed as no nurse was checking on me or wanted to help me move my baby from feeding and safely back in the bassinet. This was because they didn’t have a protocol for a lockdown situation. I felt unsafe in the hospital. […] I hate to think what first time mothers experienced during lockdown; I was lucky that I knew what I was doing but the damage has been done. I have needed therapy and counselling and have PTSD from the lockdown experience. It was the most stressful time of [my] life. It is a time I will never get back, birthing a baby is a sacred and ‘once in a lifetime’ experience, and I am heartbroken that that was my last experience of childbirth.”

Farewelling a loved one

Distress at not being able to visit a dying loved one in a rest home, hospice or hospital care was one of the most recurring themes in our public submissions and engagements we held with bereaved families. The limited number of people able to attend funerals and tangihanga during lockdown was another. The predominant view expressed by submitters was that these restrictions were cruel and unnecessary. Some were frustrated that the approach was not flexible enough and failed to take into account unique circumstances, others we spoke to described challenges in accessing the exemption process, a lack of clarity in who could apply, and the unsatisfactory automated response they received. However, where exemptions were granted, such as permission to travel to a funeral, people were grateful. Many people felt their grieving process had been impeded or incomplete, and that this had long-term consequences. Again, here is one submitter whose experience was echoed by many.

“During lockdown, dad died. […] We couldn’t be with him and had to put a huge amount of trust in staff at the home to care for dad and to love him like we did. Nobody would love him like we did. Nobody would care for him like we did. Nobody could hold him like we could have had we been allowed to be with him when he died. The whole experience was absolutely awful. We weren’t able to be together as a family and grieve.”

Some submitters did however express a willingness to forego the ability to farewell a loved one if it meant that, overall, fewer people would die:

“Not being able to attend funerals or say final goodbyes is hard… But […] missing out on a funeral, or even three funerals, is a less bitter pill to swallow than being able to attend, but needing to attend twice as many.”

ii Under section 70 of the Health Act 1956, for the purpose of preventing the outbreak or spread of an infectious disease, and if authorised to do so by the Minister, in a state of emergency or while an epidemic notice is in force, the medical officer of health may exercise a range of special powers, including to “require to be closed, until further notice or for a fixed period, all premises within a health district (or stated area of a health district) of any stated kind or description.” See: https://www.legislation.govt.nz/act/public/1956/0065/latest/DLM307083.html

iii The 48-hour period 24-25 March was designated Level 3 and allowed schools, kura and early learning centres to remain open for the children of essential workers.

iv ‘Cases at the border’ are those detected in incoming travellers in MIQ.