B.6 Additional COVID-19 deaths and YLLs had New Zealand not pursued an elimination strategy, or not vaccinated

It is conceptually challenging to understand COVID-19 health loss, whether it is small or large, and how it compares to other causes of health loss.

Moreover, many early models of COVID-19 estimated the deaths that might occur for a completely unmitigated pandemic, compared to no pandemic. Neither scenario is plausible: all countries employ measures to mitigate or reduce deaths compared to an unmitigated ‘let it rip’ pandemic, and no country could avoid COVID-19 entirely.

One useful thought experiment is to ask, ‘What would have been the additional health loss for Aotearoa New Zealand if the country had followed the approach the United Kingdom took (a mix of suppression and mitigation), compared to the elimination strategy New Zealand actually took?’ An approximate estimate of the increased deaths that New Zealand might have experienced is to apply the difference in cumulative COVID-19 death rates for 2020 to 2023 inclusive for the United Kingdom compared to New Zealand and multiply that into the New Zealand population. Using numbers from Our World in Data,16 this calculation gives 14,000 additional deaths in New Zealand, or about 41 percent additional deaths, for the four year period (2020-2023). This equates to approximately 10 percent additional deaths in each of the four years from 2020 to 2023, which is sizeable.

However, these deaths are more likely to be among the elderly and the frail, meaning a conversion of these deaths to years of life lost may be more meaningful. When we do this, we estimate that the United Kingdom’s approach applied to Aotearoa New Zealand, compared to the New Zealand experience as it actually happened, might have resulted in an additional 110,000 years of life lost over the four-year period 2020 to 2023. This equates to about 4 percent of all years of life lost from other deaths over the 2020 to 2023 period.

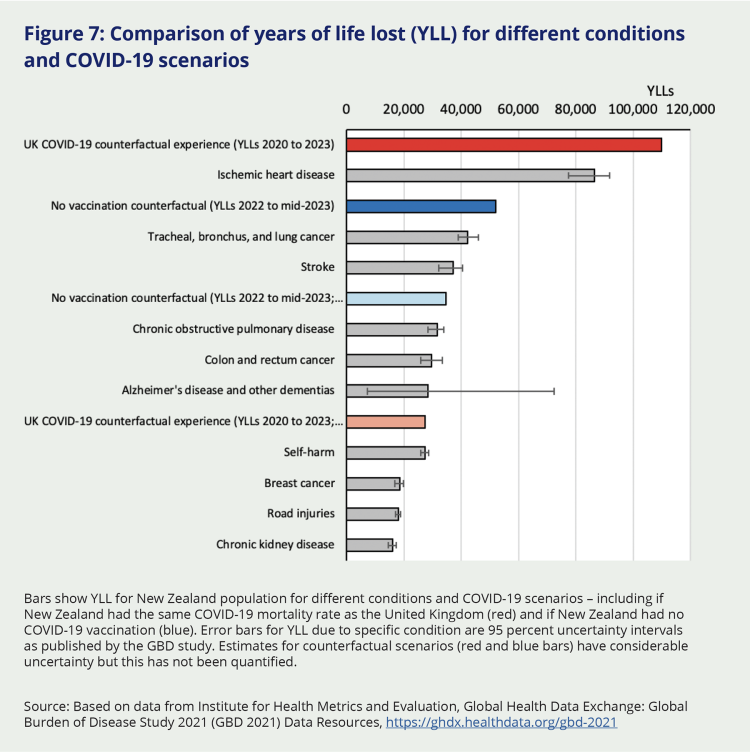

Another way to understand the health gains of an elimination strategy as run in Aotearoa New Zealand, compared to the suppression or mitigation strategy as run in the United Kingdom, is to compare the additional YLLs New Zealand would have incurred if it had run the United Kingdom strategy (dark red bar, Figure 7) to the top ten ranking non-COVID-19 YLLs in 2021 (grey bars). The YLLs from COVID-19 deaths over the four years 2020 to 2023 exceed the top cause of death, ischemic heart disease. But once annualised and spread over the four years (light red bar), the YLLs reflecting the United Kingdom versus New Zealand’s experience rank between the sixth (Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias) and seventh (self-harm, suicide) causes of annual YLLs.

Figure 7: Comparison of years of life lost (YLL) for different conditions and COVID-19 scenarios

Bars show YLL for New Zealand population for different conditions and COVID-19 scenarios – including if New Zealand had the same COVID-19 mortality rate as the United Kingdom (red) and if New Zealand had no COVID-19 vaccination (blue). Error bars for YLL due to specific condition are 95 percent uncertainty intervals as published by the GBD study. Estimates for counterfactual scenarios (red and blue bars) have considerable uncertainty but this has not been quantified.

Source: Based on data from Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, Global Health Data Exchange: Global Burden of Disease Study 2021 (GBD 2021) Data Resources, https://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-2021

How does one judge whether the health gains from running an elimination strategy, versus having run a suppression or mitigation strategy (as in the United Kingdom), were worth it? This is a challenging question to answer as we must weight differential impacts across health, economic and social domains – and such weighting is inherently value-based, with no technocratic ‘right’ answer. What we can say, here, is that:

- An elimination strategy, compared to a suppression or mitigation strategy used in the United Kingdom, gains a substantial amount of health as measured by metrics such as excess deaths (Figure 3) or YLLs (Figure 7).

- Some of the social impacts of Aotearoa New Zealand’s strategy were less than the United Kingdom’s strategy if we use the PHSM stringency index as a metric (Figure 4). However, this is just one of many social impacts. For example, international border closures in New Zealand kept family and loved ones separated for two years unless they went through MIQ. New Zealand’s elimination strategy was also accompanied by vaccine mandates that the United Kingdom did not have (although New Zealand could have run its elimination strategy with lesser mandates), with resultant breakdown in social cohesion and marginalisation for many. There are many other such social considerations we cover in this report.

- The economic impacts were variable. The initial GDP impact in New Zealand was less than in the United Kingdom, but the fiscal cost to the New Zealand Government of wage subsidies to allow stringent lockdowns was large and the long tail of harder to quantify economic costs due to border closures was substantial.

Timing also matters. Counterfactually, it’s possible that Aotearoa New Zealand could have opened up earlier (or later) with little impact on net health loss – but with marked differences in social and economic impacts.

It is beyond the scope of this report, and our terms of reference, to undertake full-blown cost-benefit analyses for alternative ways Aotearoa New Zealand could have managed COVID-19. But these types of thinking – weighing up health, social and economic impacts of policy choices, considering small or large changes that could have been made to New Zealand’s approach to COVID-19 – imbue our report. And we apply this type of thinking not only to COVID-19, but to scenarios of what a future pandemic might look like.

Also shown in Figure 7 are the additional YLLs for another counterfactual, namely if Aotearoa New Zealand had not administered any vaccine but run the same elimination strategy and border reopening timing as actually occurred.iv Datta et al (2024) undertook modelling of this very question and estimated that 74,500 YLLs were gained by vaccination. Their YLL estimate is likely to be somewhat generous since it assumed that people dying of COVID-19 had the same remaining life expectancy as other people of the same sex and age who did not die of COVID-19. This is unlikely since deaths from COVID-19 were more likely where the infection occurred in people with co-morbidities who would therefore have lower remaining life expectancy than healthy people of the same age. We therefore discounted Datta et al’s YLL estimates by 30 percent, based on Milkovska et al’s17 estimate that – on average – YLLs due to COVID-19 are about 30 percent less than estimates derived from standard lifetables. This gives an estimated additional 52,150 YLL if New Zealand had not administered any vaccine (dark blue bar). If we annualise the YLLs prevented by vaccination over the 18 months of 2022 to mid-2023 (34,767 YLL – light blue bar), we can see that the vaccine gains ranked between the third (stroke) and fourth (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease) leading annual causes of YLL health loss in New Zealand.

iv While such a counterfactual is somewhat unlikely – i.e. New Zealand would probably not have continued running an elimination strategy through to late 2021 if vaccines were not forthcoming – it does help to answer the question ‘what was the impact of vaccines?’