2.4 What happened: pandemic strategy and tools I aha: te rautaki me ngā utauta mate urutā

Having described the structures that the Government used to make decisions and run the response to COVID-19, we turn now to the evolution of the response strategy and how it was communicated.

2.4.1 The international context: three main strategic goals

Reviews of global COVID-19 responses describe three main strategic goals that countries adopted to guide their pandemic responses: elimination, suppression and mitigation.48 Some island jurisdictions were able to adopt an early ‘exclusion’ goal: namely, they kept the virus out by effectively closing their borders before any cases had occurred in their populations. An elimination goal will normally be time-bound, and at some point would be replaced by measures aimed at the third strategic goal – suppressing and/or mitigating the impacts of the pandemic agent. The three goals can be broadly summarised as follows:

Figure 4: National public health strategies used in response to the COVID-19 pandemic

| Strategy* | Public health aim | Specific objectives | Common public health measures |

|---|---|---|---|

| Elimination | Eliminate any community transmission |

|

|

| Suppression | Active measures to reduce transmission |

|

|

| Mitigation | Protect vulnerable groups from infection |

|

|

*In some jurisdictions (e.g. Australia) the term ‘aggressive suppression’ is used in place of ‘elimination’. In some analyses(e.g. König & Winkler, 2021)49, suppression and mitigation strategies are treated as a single approach.

Source: Adapted from 3 sources: Baker MG, Wilson N, Blakely T. , 2020, Elimination could be the optimal response strategy for covid-19 and other emerging pandemic diseases. BMJ 2020;371:m4907 https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m4907; Wu S, Neill R, De Foo C, Chua AQ, Jung AS, Haldane V, Abdalla SM, Guan WJ, Singh S, Nordström A, Legido-Quigley H. Aggressive containment, suppression, and mitigation of covid-19: lessons learnt from eight countries. BMJ 2021 29;375:e067508 https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj-2021-067508; Grout L, Gottfreðsson M, Kvalsvig A, Baker MG, Wilson N, Summers J. Comparing COVID-19 pandemic health responses in two high-income island nations: Iceland and New Zealand. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health. 2023;51(5):797-813. https://doi.org/10.1177/14034948221149143

In responding to COVID-19, New Zealand used all three strategies: elimination until late 2021, suppression briefly from late 2021 to early 2022, followed by mitigation. As highlighted in the following sections the transitions from one strategy to the next were fuzzy and not always well-signalled.

2.4.2 Aotearoa New Zealand quickly adopted an elimination strategy when it became apparent that zero transmission was achievable

In the first weeks of the pandemic, New Zealand’s public health response drew on elements of the New Zealand Influenza Pandemic Plan 2017,50 but without articulating a clear overall goal. At the day-to-day level, there was a strong initial focus on ‘keeping it out’ and ‘stamping it out’, which (as outlined in the Plan) would buy the time for planning. At this stage, the response was largely based on the assumption that New Zealand would ‘flatten the curve’ to protect health services using a mitigation strategy or would suppress the virus and repeatedly ‘stamp out’ outbreaks. This assumption was also reflected in public discussions and information.

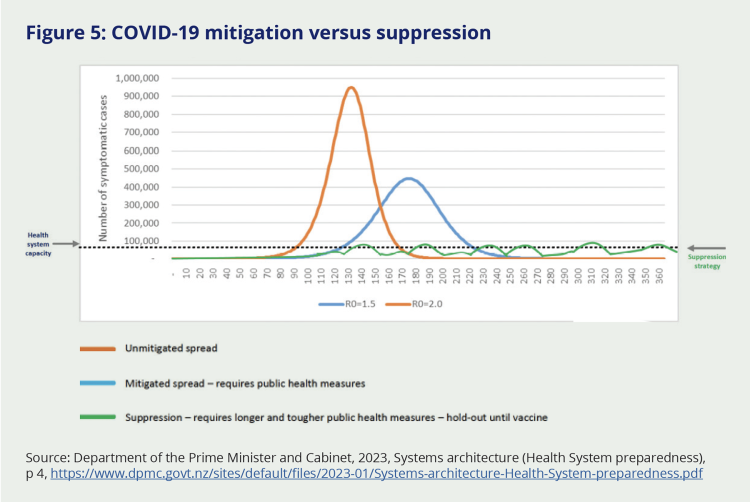

By mid-March 2020, a (now locally famous) graph was circulating among decision-makers and politicians:51

Figure 5: COVID-19 mitigation versus suppression

Source: Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, 2023, Systems architecture (Health System preparedness), p 4, https://www.dpmc.govt.nz/sites/default/files/2023-01/Systems-architecture-Health-System-preparedness.pdf

Two public health strategies were being considered at the time. One was suppression – using public health measures to suppress viral transmission and ‘flatten’ peaks of infection. The other was mitigation, where ‘light touch’ to moderate public health measures are used to flatten and make longer the first wave of transmission to lessen the pressure on health services, and simultaneously protect vulnerable people from infection (see section 2.3.1 for further discussion of the different public health strategies). The graph suggested that neither of these approaches would be sufficient to prevent the health system from becoming overwhelmed. With a mitigation strategy (blue line), the peak of infection would be less than if no measures were used (‘unmitigated spread’ – the orange line), but the number of people becoming sick and needing hospital care would substantially exceed health system capacity (dotted line). Even with a suppression strategy – leading to repeating waves of infection of much smaller magnitude (green line) – the health system might be overwhelmed at points of peak infection.

Seeing this graph was described to us as a ‘penny dropping’ moment. Many realised that – even under a suppression strategy – there was a risk that New Zealand’s health system would be overwhelmed. This realisation was presented to us as the point at which it became clear that decision-makers needed to consider taking extraordinary measures in order to protect the population from a potentially catastrophic scenario.

That the vast majority of decision-makers were not thinking of elimination as a potential strategy before mid to late March 202052 reflected WHO’s advice not to use travel and trade restrictions (which would be necessary if pursuing elimination) as control measures.53 This aligned with prevailing expert opinion at the time, which held that border controls could delay entry of a pandemic but not prevent it.54 However, as events evolved in late March, New Zealand – along with other countries in the region – elected to break with this advice.

On 23 March 2020, the country moved into Alert Level 3 (effectively, a ‘soft’ lockdown) and announced that Alert Level 4 (or a ‘hard’ lockdown) would start at 11:59 pm on 25 March 2020. Noting what was occurring elsewhere in the world, officials indicated that we had ‘a short window of opportunity to take a trajectory more similar to Singapore and others who have taken an early and strong approach to containment.’55 A ‘go hard, go early’ approach might avoid the trajectory of Europe where hospitals had been overwhelmed by people sick from COVID-19 infection. At this stage, there was not a consistent view or realisation that elimination was possible or even the goal in Aotearoa New Zealand.

The combination of strict border restrictions and stringent public health and social measures was even more successful than anticipated, and – over the next few weeks – it became apparent that eliminating the virus was a viable possibility.

2.4.3 Elimination

The pursuit of zero transmission (most of the time, knowing there would likely be some occasional incursions) emerged as the goal for Aotearoa New Zealand, to be achieved through an elimination strategy. On 9 April 2020, papers for the COVID-19 Ministerial Group explicitly articulated the elimination strategy for the first time:

“Our overall approach is to eliminate the virus from New Zealand. We will keep it out of the country with border restrictions and stamp it out wherever and whenever it occurs, minimise its spread and severity with systematic public health measures, […] and do all this until a vaccine or effective treatment emerges.” 56

The strategy was embarked on at a time of high uncertainty. Decision-makers were informed by data and high-level modelling, as well as the international situation, and advice on how Aotearoa New Zealand and our population would be impacted. New information on the virus – and how to prevent its transmission – was coming in daily. Decisions had to be made quickly, with imperfect information, and at pace. Officials attempted to look ahead at what was coming so they could offer advice on what was needed next, but this forward gaze was only able to anticipate events that lay a few weeks ahead.

Advice from this period refers to a future time when ‘a vaccine or effective treatment’57 would be available. However, there appears to have been no explicit forward work programme available to reassess the elimination strategy. Nor was it specified how and when a range of scenarios and policy response options for future strategic directions would be considered as the situation evolved or as new options for managing the virus became available.

New information on the virus – and how to prevent its transmission – was coming in daily. Decisions had to be made quickly, with imperfect information, and at pace.

Spotlight: The Alert Level System | Te Anga Taumata Whakatūpato

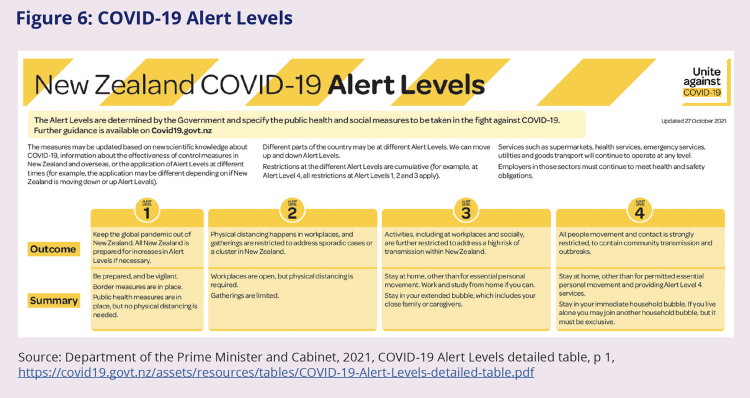

In the early stages of its response, Aotearoa New Zealand adopted a graduated set of public health measures or ‘alert levels’, which was central to the country’s COVID-19 response.

Prior to COVID-19 – and consistent with international guidance – New Zealand’s planned response to a pandemic did not include the possibility of closing the country’s borders and eliminating transmission over a sustained period.58 The initial strategy was to prevent or delay the virus’s arrival (‘keep it out’) and control any initial outbreaks (‘stamp it out’) in order to buy time for the country to prepare for widespread transmission and resultant illness (as seen in other countries). This initial strategy was supported by the introduction of a range of public health and social measures intended to limit the spread of infection.

In this early stage of the COVID-19 response, combinations of public health and social measures were grouped into four levels or ‘settings’ of increasing strictness. The Alert Level System become a central feature of New Zealand’s COVID-19 response. It gave decision-makers a simple way of ‘turning the dial up’ (or down) on infection control measures, and it gave the public a clear set of rules about what measures and restrictions they needed to follow at any point in time.

Figure 6: COVID-19 Alert Levels

Source: Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, 2021, COVID-19 Alert Levels detailed table, p 1, https://covid19.govt.nz/assets/resources/tables/COVID-19-Alert-Levels-detailed-table.pdf

At lower system settings (Alert Levels 1 and 2) people were encouraged or required to physically distance from one another, to avoid unnecessary travel, and (later) to wear facemasks on public transport and other shared indoor spaces. Alert Level 2 also included limits on large gatherings. As the risk or scale of transmission grew, higher alert levels and increasingly stringent measures came into effect. Alert Levels 3 and 4 can be understood as ‘lockdowns’ (and this is how they were popularly known), because they involved closures of schools and businesses, restrictions on gatherings, and stay-at-home orders (see Chapter 3 for more on New Zealand’s use of lockdowns during the pandemic).

Cabinet adopted the Alert Level System on 20 March 2020. The country moved to Alert Level 3 on 23 March 2020, followed 48 hours later by Alert Level 4. This marked the beginning of New Zealand’s first national COVID-19 lockdown.

Decisions about moving up or down the alert levels, or adjusting the settings at each level, were made by Cabinet, taking particular account of advice from the Ministry of Health (as the lead agency in the state of national emergency) about the public health risk posed by COVID-19, as well as advice on specific non-health factors (such as the impact on the economy, society, and at-risk populations and operational issues). Sometimes Cabinet set the whole country at the same alert level; at other times, different regions were at different alert levels.

Once Cabinet made its decisions, a team of officials in Wellington was charged with developing operational policy. This typically happened at pace and with little or no time for broader engagement – including with those in the public and private sectors who would need to implement the relevant changes. Whenever alert levels changed or the settings at each level were adjusted, people on the ground had to find quick solutions for a raft of unanticipated operational challenges. Putting policy changes into practice become easier as people learned and adapted, but the speed and frequency of change remained a challenge.

2.4.4 Moving from elimination to ‘minimisation and protection’

Just as it was difficult to identify exactly when the elimination strategy began, it is difficult to pinpoint exactly when it ended.

In August 2021, Aotearoa New Zealand recorded its first community-transmitted case of the new, and highly infectious, Delta variant. Unlike previous incursions, it was unclear if the resulting Delta outbreak could be brought under control. If not, the result would be established COVID-19 transmission and the end of the elimination phase of New Zealand’s COVID-19 response. An immediate nationwide return to Alert Level 4 lockdown was announced. The Alert Level System was again successful for most of the country, and community transmission was prevented in most regions – apart from Auckland, where Delta took hold. While the rest of the country moved back down the alert levels after a few weeks, Auckland spent more than three months in Alert Level 3 or 4 lockdown in the second half of 2021, and case numbers there continued to grow. Outbreaks also took hold in Northland and Waikato, prompting regional lockdowns. (See Chapter 3 for more on the use of lockdowns in this period.)

By October 2021, Auckland had spent seven weeks in a lockdown that had initially been signalled to last for at least one week, and ministers and officials were aware that ‘social licence’ for compliance was beginning to erode.59 On 4 October 2021, the Prime Minister noted in a press conference that New Zealand would ‘move to a framework that reflects a more vaccinated population’, thus transitioning away from the elimination strategy.60 There had been no lead-in discussion prior to this press conference about when to move from elimination to either suppression or mitigation and the announcement was not prominent in the Prime Minister’s remarks, though it was picked up and reported by the news media.61 The Prime Minister did not clearly identify the strategic goal that would replace elimination, though her description of ‘controlling the virus to the best of our ability’ is consistent with a suppression strategy.62

Other sources support the inference that Aotearoa New Zealand started transitioning to a suppression strategy around this time, although there were no public communications on this transition. On 8 October 2021, the Strategic COVID-19 Public Health Advisory Group recommended the adoption of a ‘minimisation and protection’ strategy.63 This advice took account of ‘the wish to avoid lockdowns’ while still ‘minimis[ing] the occurrence of COVID-19 and protect[ing] people as far as possible from the adverse effects of this disease’. In practice, it involved a mixture of ‘suppression’ and ‘mitigation’ elements.

Officials had been preparing advice on a new ‘COVID-19 Protection Framework’ (also known as the ‘traffic light’ system) to replace the Alert Level System once population vaccination was sufficiently high. Cabinet had agreed to this approach in principle on 27 September 2021; it was confirmed on 18 October 202164 and subsequently aligned with the new ‘minimise and protect’ strategy.65 The move to the new ‘traffic light’ system was announced on 22 October 2021 and took place on 2 December 2021.66 Auckland and several other regions were set at ‘Red’, and the rest of the country at ‘Orange’.67

The introduction of the ‘traffic light’ system and the associated transition away from the elimination strategy were somewhat contentious. The National Iwi Chairs Forum had wanted the transition to be delayed on the basis that more time was needed to ensure adequate vaccination among Māori. Despite significant efforts, vaccination levels continued to be substantially lower in Māori and Pacific communities68 and were not projected to reach 90 percent across Auckland until mid-December 2021.69 Similarly, a group of health and science experts convened by the Prime Minister’s and Ministry of Health’s Chief Science Advisors recommended that the shift to the ‘traffic light’ system should not take place until vaccine coverage was at least 90 percent, including for Māori.70 This was also in line with advice from Health officials.

However, representatives of local government and the social sector in Auckland told us that alternative views were also being advanced. There was anger at the ongoing extension of the lockdowns, a belief that Wellington didn’t understand what it was like on the ground in Auckland, and a loss of hope at the lack of an end date. Businesses in central Auckland were also calling for a plan and clearer communication on when the Auckland lockdown would end. These issues are discussed further in later chapters in this report.

Official documents from this period also illuminate the challenging situation in which the Government found itself. On one hand, there was clear recognition of ‘eroding social licence’ among the Auckland population ‘who [have] endured a significant time at heightened Alert Levels’.71 Advice highlights the ongoing and increasing challenges related to financial support and economic, social and wellbeing impacts. General fatigue amongst the public was increasing and willingness to comply with some public health measures was reportedly reducing.72 On the other hand, officials were also acutely aware of the risks of removing restrictions while vaccination levels remained low in vulnerable population groups. The specific demographics of Auckland were relevant here, with recognition that South Auckland communities in particular ‘feature[d] a younger age structure, lower rates of vaccination and [were] likely to be at greater risk of hospitalisation’.73

Confirmation that Aotearoa New Zealand was no longer pursuing elimination was hard for some people to adjust to. We heard about reluctance on the part of decision-makers to explicitly announce the end of the elimination strategy because of anticipated public fallout from the health impacts of COVID-19 becoming established. Similarly, the Community Panel cautioned that a move to the ‘traffic light’ system would ‘create a lot of uncertainty and anxiety’.74

Spotlight: Traffic Lights – the COVID-19 Protection Framework | Ngā Rama Ikiiki – te Anga Ārai KOWHEORI-19

The introduction of the COVID-19 Protection Framework was presented as supporting the new strategic goal of ‘minimisation and protection’.75

The ‘traffic light’ system had only three levels (compared with the four alert levels) and used less stringent controls (see Figure 7). Significantly, it did not involve lockdowns or the closure of businesses and schools.76 Another key change was greater freedom for those individuals who could demonstrate they had been vaccinated against COVID-19, although this (and the use of My Vaccine Pass) was removed in early April 2022. Capacity limits were also increased at this point.76

The ‘traffic light’ system was deliberately pitched at a more general level of detail than the Alert Level System on the basis that lead agencies would develop more comprehensive guidance for each sector.75

Figure 7: COVID-19 Protection Framework (summary)

| Colour setting | Control measures |

|---|---|

| Green |

|

| Orange |

|

| Red |

|

Source: Adapted from Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, 2021, COVID-19 Implementing the COVID-19 Protection Framework [CAB-21-MIN-0497], p 31, https://www.dpmc.govt.nz/sites/default/files/2023-01/COVID-19-Implementing-the-COVID-19-Protection-Framework.pdf

There were no specific criteria for moving between different traffic light levels, although Cabinet agreed that the following factors would be taken into account in decision-making:

- Health factors: vaccination rates, health system capacity, testing and contact tracing capacity, COVID-19 transmission.

- Non-health factors: effects on economy and society, impacts on at-risk populations, public attitudes, operational considerations.77

The COVID-19 Protection Framework (‘traffic light’ system) was widely viewed as less clear than the Alert Level System. An expert health group reviewing a draft version was ‘near unanimous in its skepticism about this framework in its current form’.78 (The group was particularly critical of the lack of Māori input or ‘codesign’ of the framework). Many of the group’s recommendations were incorporated into the final version of the framework. Public survey data from late 2021 suggested that the introduction of the ‘traffic light’ system was associated with significant public confusion.79 The Human Rights Commission noted that businesses and members of the public had found the ‘traffic light’ system difficult to understand and implement. The Chief Human Rights Commissioner was also concerned that the system’s differential treatment of vaccinated and non-vaccinated people could undermine social cohesion and exacerbate intolerance, noting in March 2022 that ‘the ‘traffic light’ system has caused a lot of distress to some people’.

The ‘traffic light’ system was retired on 12 September 2022, although related mask mandates remained in place for healthcare and aged care settings.80

2.4.5 Retiring the ‘minimisation and protection’ approach

The phrase ‘minimisation and protection’ was never widely adopted or understood by the public. Agencies, other stakeholders and submitters to the Inquiry were generally unclear about when the elimination strategy ended and what strategic goal replaced it.

According to the Ministry of Health, the minimisation and protection approach (officially the COVID-19 Protection Framework) was in place from December 2021 to September 2022.

In September 2022 Cabinet agreed to formally retire the minimisation and protection strategy and move to a ‘long-term approach to managing COVID-19’.81 The ‘traffic light’ system was formally discontinued at this time, signalling the end of Aotearoa New Zealand’s COVID-19 pandemic response.

The phrase ‘minimisation and protection’ was never widely adopted or understood by the public.