6.5 What happened: social impacts and responses Tā mātau arotake: ngā pānga pāpori o te mate urutā me te urupare a te Kāwanatanga

6.5.1 The pandemic and the response affected everyone, but some people and groups experienced negative impacts disproportionately – and these often deepened over time

The COVID-19 pandemic had far-reaching consequences for all aspects of our lives, and everyone was impacted in some way by the pandemic and the responses to it. Some impacts were immediately apparent and had clear causation; others emerged later and were the result of multiple pandemic response measures and their flow-on consequences.95 As disadvantage typically accumulates and intersects in ways that may not be revealed in data, it is possible that the extent of the pandemic’s impacts on some people has not yet been fully identified.

As we have already noted, people in at-risk groups and already disadvantaged at the start of the pandemic tended to be those most impacted and had less scope to adjust, particularly when they also had one or more exacerbating risk factors. These included low incomes or material hardship; insecure housing; mental health and addiction challenges; unemployment, underemployment or insecure employment; and experience of family violence or sexual violence. When people belonged to multiple ‘at risk’ groups, the impacts amassed, and those least able to absorb the shocks faced the most impacts. A few weeks into the global pandemic, the OECD highlighted what all this demanded of governments: ‘Vulnerable and disadvantaged groups will be impacted more severely and therefore require particular attention in the policy response.’96

These views were echoed in many of our engagements with government and community organisations. For example, Te Pai Ora SSPAxx told us:

“[There were] many inequities before but COVID has had a deepening effect on those. We’re only beginning to understand those significant impacts and long tail – especially for tamariki and rangatahi.”

The evidence we received makes it clear that, from the start of the pandemic response, government agencies and Cabinet were aware of the risks to many vulnerable groups. Thus, alongside ‘across the board’ measures aimed at helping everyone withstand the impacts of the pandemic, Government did seek to mitigate the pandemic’s harmful effects on vulnerable groups through various targeted interventions (see section 6.4.1). For some groups, these mitigations meant they came through the pandemic better than would otherwise be the case. Other groups did not receive many targeted interventions, but generally came out of the pandemic alright. But there were some groups that experienced negative impacts that were disproportionate to others.97

We recognise that no government anywhere in the world can fully meet the needs of every group in society; whatever measures are taken, some will be inadvertently left out or disproportionately impacted, and there are limits and opportunity costs to the amount of social welfare supports that can be provided. Nevertheless, based on what we heard and saw, it is incumbent on us to identify some of the pandemic’s disproportionate effects that surfaced during our Inquiry. We hope that doing so not only builds awareness of groups who were excluded from or poorly-served by the pandemic response, but also helps Government – or charitable and social support agencies in the community – to better tailor support to these groups in a future pandemic.

The following is a brief survey of the various categories of impacts we saw, and some of the groups affected. It is not intended as a comprehensive analysis of every vulnerable group, nor of all the impacts they experienced. Various agencies, independent organisations and researchers have undertaken such analyses, and their reports and reviews (detailed in the Endnotes) should be consulted.

We recognise that no government anywhere in the world can fully meet the needs of every group in society.

6.5.1.1 Some vulnerable groups came through the pandemic better than expected, as a result of targeted mitigations

Older people

When the pandemic began, the group considered to be most at risk of becoming seriously ill or dying from COVID-19 was older people. For example, a University of Otago modelling study published in March 2020 estimated that nearly 89 percent of the deathsxxi that would occur under various scenarios would be people aged 60 years and over.98

In the event, more older people did diexxii (particularly those aged 80 years or more) than people in other age groups.99 But by other health, economic and social measures, overall this group fared comparatively better than expected – and better than many other population groups.100 Aotearoa New Zealand’s overall low cases and deaths compared to other countries was a major gain for the most at risk, including older people.101 Economically, the pandemic response contributed to growing housing prices, which tended to disadvantage younger people and benefit people owning houses.

Older people were considered explicitly in decision-making – for example, they were defined as ‘a high-risk and prioritised population’ in a March 2020 Cabinet paper establishing vaccination priorities102 – and were given specific attention in COVID-19 communications. As a whole, older people generally fared relatively well financially thanks to superannuation providing income stability. We recognise, of course, that some older people suffered from loneliness and isolation, especially when it was not possible for whānau to visit or support them, and of course some members of this group would not have fared as well as others. We also heard from engagements with groups representing older people that many resented being cast as vulnerable and fragile, and also reacted negatively toward “ageist” attitudes towards the value of their lives.

People experiencing homelessness or insecure housing

People experiencing homelessness are among those most at risk in the face of disasters. During COVID-19, people sleeping rough and those in precarious housing were well supported in the short term. Housing and supports were provided to mitigate the transmission risk to the wider population. As a result of extra resourcing and more than 1,200 COVID-19 accommodation places available during the pandemic, people experiencing homelessness received better support during the pandemic then either before or after. See also Chapter 3.

Māori

Those Māori who entered the pandemic with existing economic, health and social inequities faced disproportionate impacts from COVID-19 that affected all aspects of their hauora.103 Despite facing negative impacts, many also had strong positive protective factors. Coupled with targeted mitigation, in our view this meant that they came through the pandemic better than expected.

Māori experienced higher hospitalisation and death rates from COVID-19.104 However, relative inequalities were less than had been anticipated (given the Māori health inequities entering the pandemic and experience in previous pandemics) due to the elimination strategy.

Entering the pandemic, Māori (alongside Pacific people) already experienced the highest rates of income poverty and material hardship across ethnic groups.105 While loss of income affected all groups during the pandemic, the Treasury noted that ‘periods of sharp and short increases in unemployment during the pandemic period seem to have affected Pacific peoples, Māori and Asian peoples more than other ethnicities’.106 Higher unemployment,107 alongside over-representation of Māori in the ‘precarious’ economy (which was not well covered by Government wage and other support policies: see section 5.3.3 and 5.3.4) points to Māori facing additional financial impacts on top of their pre-existing high poverty rates. In the view of Te Puni Kōkiri, even with mitigations in place, those Māori already in poverty experienced greater levels of material hardship and financial stress during the pandemic.108

Māori families are more likely to be larger and multi-generational, which complicated the concept of ‘bubbles’ and made strict compliance with lockdown difficult. Isolation from their wider whānau and hapū meant some people lacked their usual supports, while young people with lower access to digital devices and connectivity fell behind when learning online.109 Māori were more likely to experience family violence (see section 5.5.4).110 Māori also experienced cultural impacts as the need to adapt kawa and tikanga meant important practices like tangihanga (funeral ceremony) caused grief, harm and stress.111

But Māori also have unique cultural strengths,112 and social and institutional infrastructure; for many, these functioned as protective factors in the pandemic. Māori culture is whānau-centric, and in Te Ao Māori, the principles of manaakitanga and whanaungatanga – the ethics of care and kinship responsibility – cement the identity of Māori as tangata whenua. Iwi, hapū and marae provided the social infrastructure that enabled many individuals and groups to respond to the crisis effectively and appropriately.113 Iwi and Māori also benefited from targeted steps to mitigate the predicted impacts. Government invested more than $900 million in a range of initiatives including strengthening Whānau Ora, growing Māori job opportunities, supporting Māori learners, building the capability of Māori non-governmental organisations and tackling Māori housing challenges.114

6.5.1.2 For some vulnerable groups, pandemic mitigations were not well-targeted; these groups experienced variable impacts

Children and young people

Generally, the experiences of children and young people were not given the highest priority in the pandemic response. Cabinet was mindful of the likely impacts of extended lockdowns on children and young people’s mental health and general wellbeing, which was already a significant issue before the pandemic.115 The number of critical incidents reported by Youthline and other mental health support providers rose significantly during the pandemic: 4,371 Youthline helpline incident reportsxxiii were generated in the 2020/21 year, up by 24 percent from the previous year (see also section 6.5.2).116

The full extent of COVID-19’s effects on children and young people may not be understood for some time.

Young people held a significant proportion of the low-paying, casual jobs that were impacted in the pandemic, so they were more likely to face employment disruptions. In December 2021, Statistics New Zealand noted ‘Youth have been strongly affected by the COVID-19 pandemic ... Young people play a vital role in the labour force, but our data shows that they experience much higher unemployment rates than people aged 25–64 and the overall population.’117

We discuss how school closures and loss of learning affected children and young people in Chapter 3. While the disruption to education for New Zealand students was less than most other countries, it still had significant negative impact – particularly for Māori and Pacific students, those from lower socio-economic backgrounds, and likely for students in Auckland.

We heard that the rights and interests of children and young people were not adequately considered, and child impact assessments of the COVID-19 policy responses were not routinely undertaken. New Zealand is not the only country to be criticised on these grounds. For example, the Australian Inquiry pointed strongly to the unequal impacts of the pandemic (and pandemic policies) on children, and recommended measures such as a Chief Paediatrician who – along with the National Children’s Commissioner – would be involved more actively in decision-making in a future pandemic.118

The full extent of COVID-19’s effects on children and young people may not be understood for some time.119

Rainbow communities

We saw evidence that people in the Rainbow/LGBTQIA+ communities experienced some specific impacts during the pandemic, consistent with the bias, stigmatisation and discrimination they face throughout their lives. Research into the pandemic experiences of Rainbow young people, undertaken for the Ministry of Youth Development in October 2020, found that a third of those who chose to respond to the researchers’ survey were ‘not managing well or not at all’.120 The report found that the pandemic had ‘amplified their existing mental stress’.121

The negative impacts of COVID-19 were not experienced equally across the Rainbow/LGBTQIA+ community, with certain sub-groups within it – young people, disabled people, ethnic minorities, trans people and takatāpui (Māori who identify as LGBTQIA+) – being more likely to be negatively impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic than the overall group. Representatives of Rainbow organisations we heard from identified these sub-groups as those experiencing greater mental health issues.

Ethnic minority communities

Ethnic communities are a large and diverse population group. At the time of the 2018 census, they comprised 941,571 people from an estimated 213 ethnic groups, speaking 170 languages.122 Collectively, ethnic communities make up almost 20 percent of the population.123

They reported experiencing numerous challenges during the pandemic, particularly in getting reliable, accurate information through appropriate mediums and in a range of languages – we heard from stakeholders that new migrants and those with low levels of English were the most likely to be negatively affected by the pandemic. According to a survey124 undertaken by the Ministry for Ethnic Communities during the pandemic, improving access to services and information was the most commonly reported step that Government could take to improve support for ethnic communities in a pandemic.

6.5.1.3 Despite policies and programmes to mitigate the pandemic’s unequal impacts, some vulnerable groups were still disproportionately affected

Pacific people

Pacific people were always likely to be one of the groups worst-affected by the pandemic. The impacts they experienced – social, economic, mental and physical – became notably disproportionate in mid- to late-2021 with the Delta outbreak in Auckland and slower vaccine rollout for Pacific people.125

They were over-represented in low-income occupations, many of which were classified as essential: working in supermarkets, food supply chains, and health, disability and aged care. Pacific families were more likely to live in multigenerational and sometimes crowded homes,126 putting them at greater transmission risk and meaning some health measures (distancing, staying in small bubbles, or isolating away from others at home) were impractical. Pacific families were more likely than the general population to struggle to pay for basic household costs during the pandemic,127 which led to some young Pacific people leaving school to help support their families.128 Pacific households had the lowest level of home internet access compared with other New Zealand ethnicities,129 and this had many consequences – including for online and remote learning (see Chapter 3).

All these factors – and others, including existing health inequities, systemic bias and inadequate targeted support – put many Pacific families under great stress, especially in Auckland.130 Pacific people were perhaps the most overlooked in terms of cumulative impacts.

In our engagements, we also heard that it was difficult for Pacific peoples (especially those with English as a second language) to access clear and accurate information about COVID-19 and what was expected from them, in their own language or in a format they could easily access. Additionally, spirituality is at the heart of Pacific culture; we heard from many engagements that the important roles churches play in their communities were not well understood or valued.

Women

Women, on average, experienced more economic, health and social impacts during the pandemic. Pre-existing disadvantages were exacerbated by the effect of some COVID-19 response measures.131

More women than men lost their jobs, left the workforce, or lost hours and pay and thus experienced greater employment and economic impacts, largely because they were more likely to work in impacted sectors such as tourism and hospitality.132 Despite this, the wage subsidy was more likely to be used to support jobs held by men,133 which points to a mismatch between what was occurring and the response.

Women also bore greater pressure to support and care for families.134 The pandemic placed women under considerable stress – for example, those who were working from home while caring for young children and/or sick or elderly family members.135 During lockdown in 2020, women were more likely to report a significant increase in caring demands.136 Mothers parenting alone and balancing childcare and work (or the loss of employment) faced multiple challenges.

Many critical women’s health services were disrupted, such as breast and cervical screening, and maternity services, including maternal mental health.137 Being pregnant and/or giving birth during the pandemic was very challenging for some, especially under lockdown conditions (see spotlight in Chapter 3). Plunket saw a 125 percent increase in maternal mental health-related calls between 2019/20 and 2020/21.138

Many women experienced a heightened risk of family violence and/or sexual violence139 – although the story is nuanced and emerging (see spotlight in section 6.5.4).

And even though some women entered the pandemic with existing inequalities and were a group identified as likely to face increased vulnerabilities,140 the Inquiry has found limited consideration of gender in targeted mitigation or recovery efforts. This was supported across many of our engagements, including from the National Council of Women of New Zealand:

“Women are at the core of families and communities. When we call on community resilience, we are calling on women’s resilience. For future pandemics, calling on communities requires women to be supported – both in the lead-up, and while they are carrying that heavy load.”

Disabled people

Disabled people face many challenges in their day to day lives, with existing inequities across health, economic and social outcomes. The variety of disabilities mean the pandemic produced wide-ranging experiences for disabled people, and for many it exposed and exacerbated existing disadvantage.

The nature of some disabilities meant disabled people with particular medical conditions were more likely to be immuno-compromised and thus were at greater risk from the virus. This contributed to four times the risk of hospitalisation and 13 times the risk COVID-19-attributed mortality for people with disabilities, compared with the rest of the population during 2022.141 Some disabled people could not wear masks, and this put them at greater risk of contracting the virus, and also subjected them to discrimination and abuse from members of the public who didn’t understand the mask exemptions.

Many disabled people rely on ongoing access to regular care and services, and these were disrupted during the pandemic. For example, with staffing shortages, some had their care services cancelled or rationed, leaving them without needed essential care in their homes. A survey of primary care patients found that, from August 2020 to May 2022, 24 percent of disabled people could not always get care from a GP or nurse when they wanted it (compared with 17 percent of non-disabled people). While the results are not directly comparable due to changes in the survey question, this difference was broadly of the same magnitudexxiv as before the pandemic.142

The impacts people experienced varied according to the nature of their disability. Wearing masks made it difficult for the deaf and hard of hearing communities to lip-read, while the blind and sight-impaired said suitable COVID-19 communications were not produced rapidly enough. We also heard of instances where facilities for testing and vaccination were not physically accessible, nor were the needs for neurodiverse people well-considered in those places. Parents of disabled children faced challenges with school closures, causing disruptions to routines and the loss of extra supports that were available only at school. Disabled people were already among those most lonely and socially isolated pre-pandemic, and the COVID-19 restrictions left some further isolated or marginalised, negatively impacting their mental health and overall wellbeing.143

Disabled people were identified early on as a group at greater risk.144 Government took some steps to mitigate risks through tagged funding, but the consensus from our engagements with officials and stakeholders was that these steps were inadequate. Disabled stakeholders told us that in their view, isolating cases and contact tracing was not an adequate way of protecting disabled people from the virus; they felt that the Government should have done more to prevent their exposure. Those in leadership and advocacy roles for disabled people found engaging with and advising government frustrating and ineffective.145

“We consulted and advised 18 government departments during the pandemic – which was a complete waste of our time.”

“Things went nowhere because there was no expertise in government to be able to take the information and do something with it.”

6.5.1.4 Some vulnerable groups were overlooked in the response

We have already referred to groups who effectively fell through the cracks in the pandemic response (sections 3.3 and 3.4). They included foreign workers and international students on temporary visas and Recognised Seasonal Employer scheme workers from the Pacific. Many lost their jobs but were unable to return to their home countries. They were ineligible for health, social and financial support while in Aotearoa New Zealand, although some eventually received assistance.146

People who were precariously employed or operating in the grey or gig economies also remained below the radar, often unknown to social service providers. Prisoners were another category of people who were heavily impacted by the pandemic but remained largely invisible. At high risk of the virus due to their physical environments (large populations living in close proximity with little ability for meaningful distancing, poor ventilation, and high rates of existing health vulnerabilities and co-morbidities), prisoners were subject to particularly stringent infection control measures for the duration of the pandemic. Their situation is described in the accompanying spotlight.147

Spotlight: Prison life in the pandemicxxv | Te noho i te whare herehere i te wā o te mate urutā

By some measures, the prison system’s response to COVID-19 was highly successful. Aotearoa New Zealand prisons were free of the virus until 29 September 2021. There were few hospitalisations and no deaths reported due to COVID-19.148 This contrasted sharply with prisons overseas, which recorded very high levels of illness and death, especially early in the pandemic, and became extremely effective ‘superspreading’ environments. In the United States, for example, the age-adjusted risk of dying in prison due to COVID-19 (as of 2023) was six times higher than in the general population.149 New Zealand was also one of a minority of countries to prioritise vaccination for prisoners.150

Having witnessed the toll that COVID-19 was taking in prisons elsewhere in the world, the Department of Corrections was determined the situation would not be repeated here. Consequently, New Zealand prisons implemented infection control measures that separated, isolated or quarantined prisoners. Normal services, programmes and activities were suspended and contact with the outside world was minimised. Many prisoners had no visitors for extended periods and limited time out of cells.

While effective, these infection control measures exacted a very high cost on prisoners and their whānau. When the Office of the Inspectoratexxvi investigated the use of separation and isolation between 1 October 2020 and 30 September 2021, it concluded:

“[The suspension of visits] heightened the isolation experienced by all prisoners, and also impacted on families in the community. All non-essential services, across the prison network, ceased from August 2021. This had a profound impact on prisoners, who were unable to complete rehabilitation and reintegration programmes. The focus across the prison network shifted to maintaining minimum entitlements.”151

In fact, the Inspectorate found, ‘Due to the length of the pandemic, there were some prisoners who did not receive their minimum entitlementsxxvii for prolonged periods of time’.152

It was clear from our meetings with prison staff and the Department of Corrections that many working within the system did their utmost to keep prisoners safe and prisons COVID-free. They also recognised that some prisoners’ high health needsxxviii made them especially vulnerable to COVID-19.153 As a result, Corrections said, ‘we always went the extra mile in taking a cautious approach’.

While that stringency undoubtedly kept incarcerated people safe, it also became embedded and hard to roll back. Some prison managers – who had considerable operational autonomy during the pandemic, within ‘guide rails’ set by Corrections – took a cautious approach to relaxing infection controls even once the national strategy moved on from elimination. As the pandemic progressed, Corrections began experiencing an acute and unexpected shortage of custodial staff, reaching the lowest point in January 2022. This placed greater pressure on remaining staff and affected Corrections’ ongoing capacity to return to pre-COVID-19 settings. Corrections leaders acknowledged that rolling back the restrictive regime was challenging after ‘running quick and hard to introduce controls that rightly kept people safe’.

We were surprised that the option of releasing some prisoners early was not meaningfully explored as a way to reduce COVID-19 risk in prisons. This strategy was consistent with international best practice and adopted by more than 100 countries.154 Corrections considered some initial options in April 2020, but determined it was not necessary in the Aotearoa New Zealand context. Any early release option would involve challenging trade-offs with public safety and require significant legislative change. Corrections told us it might be a tool the Justice Sector could consider for the future. We agree.

Chief Ombudsman Peter Boshierxxix criticised the prolonged use of restrictive measures. Speaking to us in December 2023, he was concerned that many prisoners were still locked down for 23 hours a day. The ‘convenience’ of keeping prisoners locked down during the pandemic had created a culture among prison staff which persisted, even though there were now better ways to protect prisoners from COVID-19. His comments were echoed when we visited Spring Hill and Auckland Region Women’s Prison in early 2024 to hear from prisoners themselves.

“Didn’t see [my kids] for two years. Talking on the phone is not the same as hugging them.”

“There used to be a way to work [in prison] and save up money … [now] people are getting out with nothing. That impacts society.”

“We got phone cards as the solution to no visits. But this was 80 men to two phones, with only an hour out of our cells.”

“I was grateful for the lockdowns, they saved lives. It’s just how they handled the lockdowns [in prisons].”

“In some units, one person got COVID, so they’d lock everyone down because of bad ventilation.”

“There’s a shit ton of repressed anger. People are processing it but it’s coming out the cracks.”

6.5.2 Mental wellbeing impacts affected all ages, with young people especially hard-hit

Like other severe crises, pandemics can have major psychological and wellbeing impacts.156 For Aotearoa New Zealand, COVID-19 was one of the biggest challenges to our collective mental wellbeing seen in many generations.157 Most people experienced some level of distress, and for many this was tolerable and short-lived. For others the stress developed into something more serious, often worsening an existing mental health condition. This is of particular concern given New Zealand’s already high prevalence of mental health and addiction issues.158

Pandemics can affect mental health in many ways. People may feel anxiety and fear about contracting the virus itself, or about the ever-present uncertainty the pandemic creates.159 But as we saw in Aotearoa New Zealand (initially at least), a strong sense of unity and a collective focus on protecting each other and saving lives can also run alongside concern, anxiety and fear.

International literature on disasters often describes these periods of unity and collective determination as heroic and honeymoon phases that give way to disillusionment when people start to realise how long recovery is going to take, and what it might take to get there.160 Some feel overwhelmed by the situation, by the unrelenting stress and fatigue, and by feelings of anger, depression, isolation, loneliness, frustration and grief. Hostility may increase, and financial pressures and relationship problems set in. The fourth stage is reconstruction, or recovery, a gradual return to life. International literature suggests psychosocial recovery can take up to ten years.161

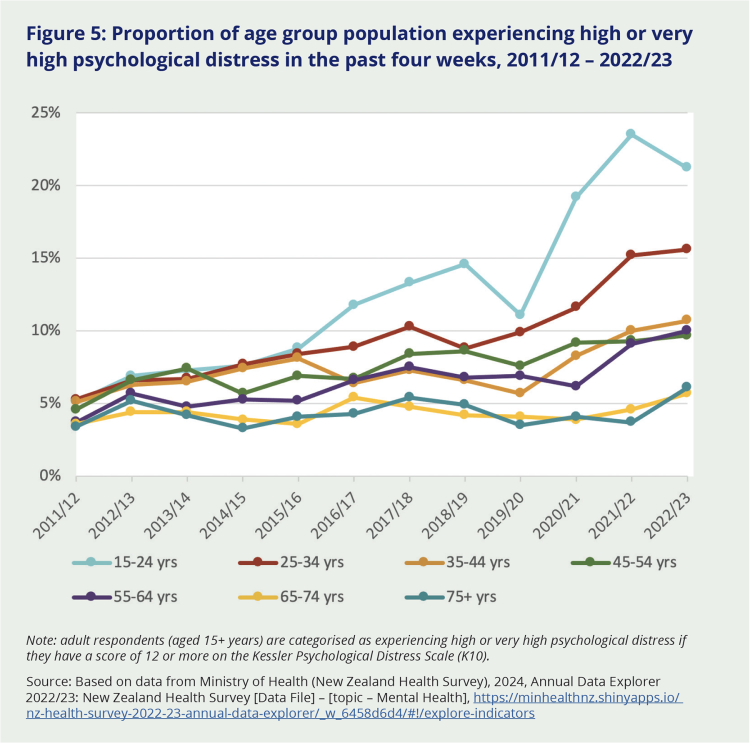

Population-level mental health is monitored as part of the New Zealand Health Survey, using the Kessler scale of psychological distress.162 As the following graph shows, rates of distress among most age groups fell between 2018/19 and 2019/20. In fact, some seemed to plateau in that first year of the pandemic, before growing (by varying degrees) over the next three years. However, the picture was different for younger age groups (15–24 and 25–34 years). Having experienced consistently higher rates of distress since 2015/16, their distress then increased more sharply than any other age group after 2020. Nearly one in four young people (aged 15–24 years) experienced high or very high levels of psychological distress in 2021/22.163

The pandemic has had an impact on the mental health of New Zealanders, but this has been unevenly felt across the population, with the most vulnerable bearing the worst impacts.155

Age is not the only factor influencing mental health indicators – living in poverty was also a factor behind these results. From the same survey, we found that people living in the most deprived neighbourhoods were 2.4 times more likely to have experienced psychological distress than those in the least deprived neighbourhoods.164 All ethnic groups experienced increased rates of psychological distress leading up to and through the pandemic.

Figure 5: Proportion of age group population experiencing high or very high psychological distress in the past four weeks, 2011/12 – 2022/23

Note: adult respondents (aged 15+ years) are categorised as experiencing high or very high psychological distress if they have a score of 12 or more on the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K10).

Source: Based on data from Ministry of Health (New Zealand Health Survey), 2024, Annual Data Explorer 2022/23: New Zealand Health Survey [Data File] – [topic – Mental Health], https://minhealthnz.shinyapps.io/ nz-health-survey-2022-23-annual-data-explorer/_w_6458d6d4/#!/explore-indicators

Evidence gathered during our Inquiry was consistent with this monitoring data. It too pointed to an increase in mental health issues, especially for young people, and was consistent with some causal effect of the pandemic and pandemic response, in addition to trends before COVID-19 (although the exact partitioning is difficult to know). We also heard about mental health impacts on children below 15 years, a group not monitored by the survey data.

We know that youth mental health issues were increasingly significant before the pandemic, and appear to have become more widespread and acute, especially anxiety, depression, loneliness and fear.165 There are likely to be many reasons. Children and young people experience the world, and the passage of time, differently from adults – meaning the pandemic probably seemed endless to many, compounded by ongoing uncertainty about when it might end and life would return to normal. Many missed key milestones or significant childhood events during what was a confusing, distressing and unusual time. We saw evidence that while there were positives for some young people – having more free time, family time and opportunities for new activities – they faced disruptions to their education, isolation from their peers and social groups, and greater susceptibility to family violence.166 Young people with jobs were also more likely to face employment disruptions,167 contributing further to their stress. Surveys carried out during the Level 4 lockdowns in April 2020 found young people with a previous diagnosis of mental illness fared worse than their peers.168 We heard that some children in care faced the unique anxiety that their foster family would not want to keep them in their ‘bubble’ during the pandemic.

These trends were reflected in the demand placed on youth mental health services. Calls to Youthline between 2019 and 2022 showed a 52 percent increase in critical incidents (when a young person presents with serious risk of self-harm or suicide).169 Calls to the mental health lines of telehealth provider Whakarongorau increased across all age groups during the pandemic, but the largest increase was in calls from young people. While calls later dropped to historic levels for 20–24-year-olds, by late 2023 they still remained high for young people aged 13–19. Since December 2021, Whakarongorau also recorded an increase in calls involving risks of suicide, abuse, harm to others and self-harm, which peaked in August 2023.

Despite this evidence of high demand from young people, the Mental Health and Wellbeing Commission reported that they had the longest wait times of any age group for acute mental health services under the previous district health board system in 2021/22.170 This suggests they are not being prioritised.

The Inquiry heard that the mental health effects of the pandemic are likely to have a long tail. This view was supported by evidencexxx showing significant and maybe even intergenerational consequences for the cohort of young people experiencing high rates of mental distress during and since the pandemic.171

6.5.3 Locally-led responses were invaluable in addressing the social impacts of the pandemic

Marae, schools, churches, NGOs and other community networks and hubs are crucial points for community connection, leadership, practical support and resilience building. Their value to society as a whole often goes unnoticed, but the COVID-19 pandemic put the spotlight on their good work, if only for a short time.

...people tended to have higher degrees of trust in the communities and groups that they were part of, or that were immediately accessible to them.

Through our discussions with stakeholders across the social sector, and other evidence, we have learned a lot about why so many locally-led responses were effective during the pandemic. For one thing, people tended to have higher degrees of trust in the communities and groups that they were part of, or that were immediately accessible to them. Second, we saw that these local responders had well-established strengths they could draw on quickly, including strong leadership, trusted relationships and diverse connections.

In our engagements, several stakeholders emphasised that those who were trusted were best placed to make and influence decisions on how to support the needs in the community. As one told us:

“People trust people – and those people now need to influence processes.”

These factors and others made local groups and networks powerful assets in the response to COVID-19.172 In our view, they must be cultivated and strengthened as part of Aotearoa New Zealand’s preparations for another pandemic. As the Ministry of Social Development noted after a 2022 evaluation of Care in the Community: ‘A locally led, regionally enabled, and nationally supported approach is emerging as a valuable framework for supporting community wellbeing and recovery.’173 Social service providers too emphasised that this was one of the central lessons of the pandemic:

“The learning is that community is the place where people get their responses. Whatever that community is you really need to resource and empower it and give it its head.”

6.5.4 Responding to the pandemic has had lasting consequences for some providers and community organisations

COVID-19 created huge social and wellbeing pressures for households and communities, compounding the financial pressures described earlier in this chapter. Right from the start of the pandemic, providers reported increasing demand for social supports and services, and an upsurge in new clients – including many who had not sought charitable support before. The extent and breadth of the pandemic’s social impacts was also apparent in the sharp rise in demand for Government support during 2020/21.174 This was largely associated with the COVID-specific programmes of assistance introduced by the Ministry of Social Development; demand for benefits increased too, but more slowly than expected. Again, a significant proportion of that demand was from people who had never before found it necessary to seek assistance from the benefit system.

Many providers and community groups lacked the necessary tools and resources to operate in the restricted and uncertain COVID-19 environment.

The burden of the pandemic’s social and wellbeing impacts was not shared equally across all New Zealanders. Similarly, the impacts experienced by providers and community organisations varied. Many lacked the necessary tools and resources to operate in the restricted and uncertain COVID-19 environment. According to the representatives of one provider we met with, these are just some of the lessons the social sector must learn from the COVID-19 response before the next pandemic; by taking them on board, the sector will be better-prepared to meet the needs of communities and those who work alongside them next time.

Staff and volunteer burnout were common themes raised by the NGO sector.

Initially, many struggled to get their status as essential services approved or clarified, and to work through what the lockdown and other restrictions would mean for them. Other providers that might have been able to operate online lacked the digital infrastructure or staff capability to do so. And for some, the nature of their services – and the fact that clients were unable or unwilling to interact with them online – made it simply impossible to make the switch. For example, see the Spotlight on family and sexual violence below.

During the pandemic, the pressure on small organisations with limited cash flow was immense. In addition, nearly all organisations relying on volunteers noted the strain they faced during and since the pandemic. In particular, they ‘lost’ older volunteers – who represented a large proportion of volunteers in many organisations – because they were told to stay home to be safe, while many others had additional family care responsibilities. As a result of the pandemic, it is clear that the delivery network of NGOs and community organisations has little surge capacity left. Providers described three years of ‘endurance working’. The health and wellbeing – and retention – of frontline staff has become a growing issue since the pandemic, as increased workloads are not sustainable. Staff and volunteer burnout were common themes raised by the NGO sector. This does not bode well for the future. We consider there is a risk that the very same network that was so critical to the delivery of the COVID-19 response may not have adequate capacity or capability to respond to another crisis, without some investment. This view was shared by many organisations we heard from, including the New Zealand Red Cross:

“Not for profit (NFP) organisations and the NFP sector are core elements of a whole of system response effort. It is important that any Government response recognises the contribution of the sector and makes it as easy as possible for NFPs to dock into and support government agency responses. The Government needs a strong NFP sector to do what the Government cannot do during these times.”

Spotlight: What happened to family violence and sexual violence? | I ahatia te whakarekereke whānau me te koeretanga kino?

Aotearoa New Zealand has long had unacceptably high rates of family violence and sexual violence, especially taking into account that these types of violence are often under-reported.xxxi In the immediate pre-pandemic period, Government took some major steps to address family violence and sexual violence by establishing a joint venture (now known as Te Puna Aonui) to deliver an integrated, whole-of-government response. However, family and sexual violence remained a significant challenge as the country moved into COVID-19.175

National emergencies and crisis situations can trigger an increase in family violence and sexual violence, and this had already happened before the COVID-19 pandemic – for example, during the aftermath of the Canterbury earthquakes.176 Specialist community organisations and providers, government agencies, and some media outlets were therefore keenly aware of the increased risk of family violence and sexual violence as the country entered Alert Level 4 lockdown in March 2020.177

The rules at Alert Level 4 reflected Cabinet’s intention to reduce this risk where possible. Leaving an unsafe home environment to stay somewhere else was deemed essential travel, and many specialist support organisations continued operating as essential services. Communications from government agencies and NGOs reflected this, encouraging people not to remain in unsafe ‘bubbles’:

“Sometimes it is unsafe for you to reach out for help while you are in the same space as the person who is hurting you. If you can’t communicate safely through phone, text, email, or social media, maybe your friends, whānau, or neighbours could help.”178

However, not everyone who needed to hear this message did. Moreover, lockdown conditions made it especially difficult for people at risk to access help without alerting the perpetrator. Safe places where violence is often reported – like schools, GPs and WellChild clinics – were either not operating or much harder to access.

“We got quite a few calls re: domestic violence. Often it was situations like, she’d always been in a violent relationship, but when he went out to work it was okay. Now they were [locked down] together it was worse. She said, [to me] ‘we’re not supposed to leave the house’, but I said ‘break your bubble next time’.”

We heard from stakeholders that, during lockdowns, some people disclosed violence to the only people they could: essential workers like supermarket staff and emergency workers. These workforces were not trained to receive such disclosures and there is no data available to indicate how often such disclosures were made or what happened as a result.

It is hard to know exactly what impact the pandemic had on the frequency of family violence and sexual violence. Some agencies were braced for a large rise in formal reports of violence early in the pandemic, but this did not occur.

Still, as Police noted in an internal report at the time, a lack of formal reporting does not necessarily indicate a lack of harm.

Many authoritative sources have reached the conclusion that an increase in family violence and sexual violence harm did occur during the pandemic. They note that, because of the nature of this type of offending and the sensitivities involved in disclosure and prosecution, incident data should never be treated as a prerequisite for action on family violence and sexual violence. Based on the evidence we have heard and reviewed, we agree.

Reporting rates aside, there are indicators that the nature and severity of family violence and sexual violence worsened during the pandemic. We heard from specialist providers that in some cases, the pandemic conditions resulted in new or opportunistic forms of violence, such as:

- Perpetrators weaponising lockdown rules to exert greater control over victims’ movements.

- Increasing reports of financial abuse and intensive digital surveillance as perpetrators were more easily able to track victims’ activities in lockdown.

- Denial of vaccination emerging as a new form of coercive control (which also served to restrict freedom of movement for victims at times when vaccination was a prerequisite for entry to certain spaces).

- Distressing reports of international students being coerced by flatmates or landlords into providing sexual favours in return for housing. This underscored a gap in protection for international students who remained in Aotearoa New Zealand during the pandemic.

It is also likely that some family and sexual violence harm during the pandemic was prevented by the swift actions of officials, decision-makers, specialist providers and community organisations and community members and community members. We heard the safety of children was front of mind for many service providers and community workers during the pandemic.

During the pandemic, a working group on family violence and sexual violence was quickly established and resourced to improve collaboration and response between government agencies and service providers, along with a Tangata Whenua Rōpū specifically for Māori organisations to advance Māori-led solutions.

Emergency funding was provided by both government179 and the private sector, and providers were able to use this flexibly and creatively. For the most part, government agencies created a supportive, high-trust environment for community organisations and specialist services to respond effectively to the emerging risks of family violence and sexual violence during the pandemic. This was appreciated by the stakeholders in the sector that we spoke to.

xx Social Service Providers Te Pai Ora o Aotearoa.

xxi The authors estimated that between 8,560 and 14,400 (0.17 percent to 0.29 percent of the population) could die in the worst scenarios which assumed the failure of the eradication strategy, high disease reproduction numbers and lower levels of disease controls.

xxii By this, we mean those for whom COVID-19 was officially coded as the underlying cause of death.

xxiii Youthline says an incident report is created whenever a Helpline volunteer or staff member has a call, text, webchat or email conversation with a client who is presenting with one or more of the following: (1) any care and protection risk (including physical abuse and sexual abuse), (2) medium to high suicide risk, (3) medium to high self-harm risk.

xxiv In the August and November 2019 quarters, 20 percent of disabled people could not always get care when they wanted it, compared with 15 percent of non-disabled people.

xxv We note that the experiences of young people in Oranga Tamariki youth justice residences were very different (and more positive) than those of the adults in the prison described here.

xxvi The Inspectorate operates under the Corrections Act 2004 and the Corrections Regulations 2005. It is part of the Department of Corrections but operationally independent to ensure objectivity and integrity. Its staff inspect and investigate many aspects of the prison system, including prisoner complaints.

xxvii Under Section 69 of the Corrections Act 2004, prisoners must receive certain minimum entitlements, which include at least one hour of physical exercise a day, and the ability to have at least one private visitor each week.

xxviii They are much more likely than the general population to have mental health and substance disorders, for example, and many other co-morbidities.

xxix The Department of Corrections initially discouraged the Chief Ombudsman and his staff from making prison inspections, despite the Ombudsman’s statutory role to provide independent oversight. This issue was resolved by late April 2020 once the inspection team received essential worker status.

xxx For example, data from the New Zealand Health Survey 2022/23 showed that one in five (21.2 percent) young people aged 15–24 years experienced high or very high levels of psychological distress in 2022/23, up from 5.1 percent in 2011/12. See endnote 171 for details.

xxxi Family violence is a pattern of behaviour that coerces, controls or harms another, within the context of a close personal relationship, and often involves fear, intimidation, and loss of freedoms. Sexual violence involves a person exerting power and control over another person without their informed consent, or where they are unable to provide consent (e.g., children, vulnerable adults). In Aotearoa New Zealand, on average, Police attend a family violence callout every three minutes. One in 3 women and 1 in 8 men will experience sexual assault in their lifetime, with even higher rates for the takatāpui and LGBTQIA+ community. These definitions and statistics are taken from Te Puna Aonui, see: Definitions and Prevalence Data | Te Puna Aonui