10.3 Lessons for the future Ngā akoranga mō ā muri ake

Overview | Tirohanga whānui

With the fundamental global observations and context from the previous section in mind, we now turn to the specific lessons Aotearoa New Zealand can learn for the future. These lessons describe the high-level elements we think are necessary to ensure the country is fully prepared for the next pandemic ahead, and ready to respond in ways that take care of all aspects of people’s lives. In our earlier chapters and reflections, we have been looking at COVID-19 through the rear-view mirror. Now we turn our attention to the road ahead.

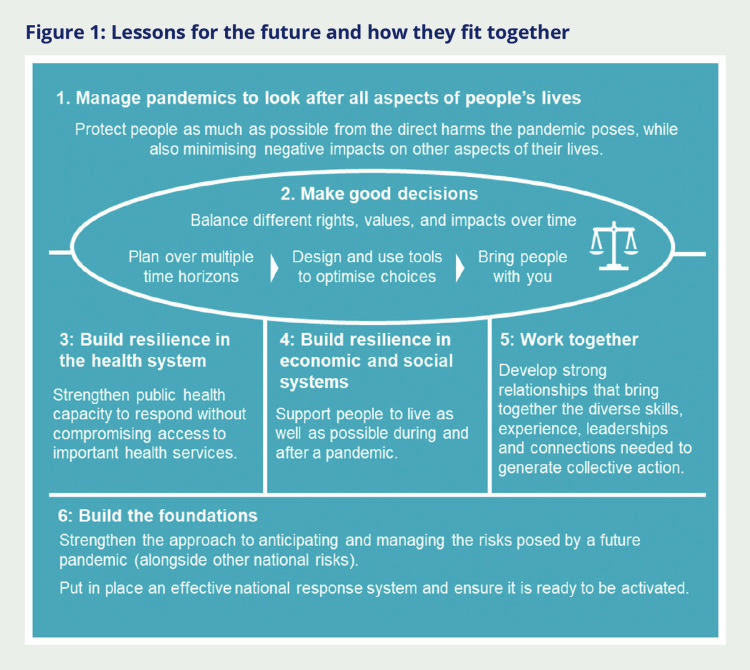

The overarching lesson from COVID-19 (Lesson 1) is that we need to manage pandemics to look after all aspects of people’s lives. This means recognising the broad range of impacts that a future pandemic may have on all aspects of people’s lives in Aotearoa New Zealand – and balancing the responses to minimise both immediate and long-term harms. The remaining five lessons for the future flow from the first. Figure 1 shows how the lessons work together.

Figure 1: Lessons for the future and how they fit together

Lessons 2 to 6 reflect what we have learned about what it would mean to prepare for and respond to a future pandemic in a way that looks after all aspects of people’s lives.

Lesson 2: Make good decisions. In order to look after people in a pandemic, decision-makers need to keep sight of the overall purpose of the response while being adaptable in how this is achieved. They also need advice and evidence that helps them weigh up different options and strike a balance between different priorities and values. What is needed to ‘look after people’ will change as the pandemic evolves and the balance of benefits and harms of various policy options shifts over time.

Lesson 3: Build resilience in the health system. Looking after people’s health is a core part of any pandemic response. Strengthening public health capacity will expand the tools available to reduce the risk of pandemic infection. This can reduce their reliance on more restrictive measures (such as lockdowns). Capacity is also needed in the healthcare system so this can meet the demands of safely caring for those who become infected while also delivering other essential health services.

Lesson 4: Build resilience in our economic and social systems. Any pandemic response needs to look after the social, economic and cultural aspects of people’s lives. In order to do this, New Zealand’s social and economic systems need to be resilient and have the capacity to ‘step up’ during a crisis. People are the most important resource, but we also need tools and processes for identifying and reaching those who need support during a pandemic.

Lesson 5: Work together. Looking after people in a pandemic means all parts of society need to be involved. Communities, businesses, faith groups, NGOs and tangata whenua are able to reach people and do things beyond the scope of government agencies. Building relationships and recognising the value of others’ approaches are important preparation for working together in a pandemic.

Lesson 6: Build the foundations for future responses. Looking after people means thinking about what would be needed in a future pandemic response and acting now to ensure this is in place ahead of time. It’s not possible to predict the exact nature of the next pandemic, or the economic and social situation in which it might occur, but there are tools (such as scenario planning) that can give a sense of the range of challenges a future government might need to respond to. These should inform what’s prioritised in the work of pandemic preparation and where Aotearoa New Zealand should focus its resources – including the tools and systems needed to look after all aspects of people’s lives.

Lesson 1: Manage pandemics to look after all aspects of people’s lives | Akoranga 1: Te whakahaere mate urutā hei tiaki i ngā āhuatanga katoa o te ao o te tangata

In brief: What we learned for the future about looking after all aspects of people’s lives

In preparing for and responding to the next pandemic:

- Lesson 1.1 Put people at the centre of any future pandemic response

- Lesson 1.2 Consider what it means to ‘look after all aspects of people’s lives’ from multiple angles

Overview

While pandemics are first and foremost public health emergencies, Aotearoa New Zealand’s COVID-19 experience demonstrated that managing a pandemic is also about much more than controlling an infectious disease. The pandemic – and the Government’s response to it – affected every part of people’s lives – health, social, economic and cultural. Preparing effectively and responding well to a future pandemic will therefore require involvement from across both sectors and society.

The COVID-19 pandemic was also a reminder of what matters most for people. Humans are social beings whose lives are made meaningful by the strength and value of our relationships and connections. Physical health and wellbeing matters, of course, but so do whānau and family, friendships, livelihoods and the freedom for individuals and communities to choose and pursue what is important to them, even during a crisis like a pandemic.

These insights are an important reminder of the core purpose of pandemic preparedness and response – looking after all aspects of people’s lives. In practice, this means:

- Looking after all aspects of people’s health – protecting them from infection, while also looking after their wider physical, mental and emotional health.

- Looking after the broader aspects of people’s lives – looking after their social, economic and cultural interests.

- Looking after people in the future as well as the present – making sure that actions and decisions in the moment take account of what may be needed in times to come.

What’s needed to ‘look after people’ may change over time. Sometimes, multiple objectives may be in tension with each other. Recognising and responding to this will require decision-makers to weigh up different options and balance potentially competing priorities and values. This is covered in more detail in Lesson 2.

When it is understood that the purpose of pandemic management is looking after all aspects of people’s lives, it becomes clear that pandemic preparedness and response need to take a broad approach. The centrality of this purpose was encapsulated by the Chair of our counterpart inquiry in the United Kingdom, Rt Hon Baroness Hallett DBE, in the introduction to her Inquiry’s first report: ‘The primary duty of the state is to protect its citizens from harm’.7 While it will be up to future governments to determine exactly how to prepare for, approach and respond to a future pandemic, and what weight to put on different forms of harm, it is hard to imagine any pandemic scenario in which protecting and supporting people through the crisis is not the primary focus.

Lesson 1.1 Put people at the centre of any future pandemic response

Many people, groups and organisations in Aotearoa New Zealand draw inspiration from the well-known whakataukī: He aha te mea nui o te ao? He tangata, he tangata, he tangata (What is the most important thing it the world? It is people, it is people, it is people). Embedded in this whakataukī is a challenge – before taking an irreversible action, consider: what will it mean for people?

Early in the COVID-19 pandemic, many people in Aotearoa New Zealand had a strong sense that the response was intended to look after them. While daily life was fundamentally changed by the introduction of border restrictions and lockdowns, strong messaging to ‘Unite against COVID-19’ and ‘be kind’ gave many people a sense that the Government was acting in their best interests. Many of our public submitters expressed gratitude for this decisive and empathetic approach, drawing attention to the contrast between the quiet streets in Aotearoa New Zealand during the first Level 4 lockdown in 2020, and images of the devastating impact of COVID-19 in parts of Europe and North America.

Over time, however, this sense of being looked after began to fade for some people. Measures such as gathering restrictions that were intended to keep people safe from the virus became a cause of distress and harm. We heard from some submitters that, in minimising the risk of infection, it sometimes felt as though people were being denied the things that made their lives worthwhile. Some New Zealanders who were overseas felt forgotten or abandoned by their home country.

The challenge for future governments will be to ensure that people – and all the things that make their lives meaningful – are kept at the centre of any pandemic response. Pandemic policies and measures should be evaluated not only for their efficacy in minimising infection, but also for the impacts they have on people’s lives. There will be times when it is necessary to use measures that come with significant costs or restrictions. But COVID-19 has underscored the importance of fully considering the impacts of pandemic response measures on all aspects of people’s lives – both short- and long-term – and taking this into account as much as possible when deciding when and for how long to deploy such measures.

Lesson 1.2 Consider what it means to ‘look after all aspects of people’s lives’ from multiple angles

It is important to take a broad perspective on what looking after all aspects of people’s lives means during a pandemic, and to embed this across all elements of the response. This is partly acknowledged in the recent interim update to New Zealand’s Pandemic Plan, which sets the following ‘key objective’:

“The key objective of this plan is to minimise deaths, serious illness and significant disruption to communities, the health system and the economy arising from a pandemic associated with a respiratory infection.”8

As we learned during COVID-19, people’s lives and quality of life can be threatened not only by a pandemic pathogen, but by the response itself. Mental health may be challenged by long periods in lockdown. Jobs and incomes may be lost. Families may be painfully separated or exposed to damaging stress and violence. Delays in accessing ‘business as usual’ healthcare may lead to people dying or becoming seriously unwell from other illnesses. There may even be longer-term, intergenerational impacts, such as loss of learning from school closures, or lack of housing affordability from response measures accelerating existing economic trends.

There are numerous models and frameworks that future decision-makers and officials can use to inform their understanding of what matters to people and what it means to look after all aspects of their lives during a pandemic. These include (but are not limited to):

- Aotearoa New Zealand’s human rights framework, comprised of a mix of domestic laws and various United Nations treaties and rights declarations which New Zealand has ratified. Te Tiriti o Waitangi is also part of this framework.

- Outcomes frameworks developed by agencies to inform their work, such as Treasury’s Living Standards Framework.

- Models developed for specific population groups, such as children and young people, Māori, Pacific peoples and other ethnic communities.

- Holistic models of mental and physical health, such as the outcomes framework developed by Mental Health and Wellbeing Commission | Te Hiringa Mahara.

Using such models and frameworks can give decision-makers confidence that they have identified a wide range of potential impacts from various pandemic response measures and support sound decision-making about which measures to use and in different circumstances.

Aotearoa New Zealand’s COVID-19 experience demonstrated that a pandemic’s impact will be unevenly distributed – especially if efforts to mitigate unequal impacts are insufficient. As set out in the ‘Looking Back’ section of the report, especially in Chapter 6, even with a proactive policy response, the COVID-19 pandemic and associated response measures disproportionately affected Māori, Pacific people, women, disabled people and others, even with a proactive policy response.

Aotearoa New Zealand’s COVID-19 experience also demonstrated that a pandemic’s impact will be unevenly distributed.

Many actions by policy makers and communities helped to reduce these impacts. For example, food parcels and other forms of grassroots support were part of the tremendous wraparound support provided to many communities during the first lockdown. But some efforts could have been more effective through, for example, earlier engagement of Māori and Pacific providers in the vaccine rollout (see Chapter 7).

Making use of the kinds of models and frameworks set out in this lesson can also help to flush out how different individuals and groups may experience a pandemic differently. Recognising that it will never be possible to completely mitigate every potential negative or unequal impact with an optimal policy response package, a people-centred future pandemic response should nevertheless aim to anticipate these were possible, consider the overarching purpose of the response, apply ethical principles to guide decision-making including trade-offs, and augment population-wide or universal policies with targeted policies as appropriate. Making use of a wide range of models and tools can inform effective planning for how to do this in a way that looks after all aspects of life for a wide range of people – recognising a pandemic is still going to see ‘losses’ in many domains. This will also help to ensure that underlying inequities and existing disadvantages are not exacerbated during a future pandemic.

Lesson 2: Make good decisions | Akoranga 2: Te tuku whakatau pai

In brief: What we learned for the future about making good

In preparing for and responding to the next pandemic:

- Lesson 2.1 Maintain a focus on looking after all aspects of people’s lives in pandemic preparedness and response. In practice, this means:

- 2.1.1 Consider and plan for multiple time horizons simultaneously

- 2.1.2 Make more explicit use of ethical frameworks to balance different rights, values and impacts over time

- Lesson 2.2 Follow robust decision-making processes (to the extent possible during a pandemic). In practice, this means:

- 2.2.1 Seek out a range of advice and perspectives

- 2.2.2 Make use of times when the situation is stable to look ahead and plan for what might come next

- 2.2.3 Anticipate and plan for burnout

- Lesson 2.3 Use appropriate tools when developing and considering policy response options

- 2.3.1 Identify a wide range of possible policy response options

- 2.3.2 Compare the impacts of different policy response options to make good decisions

- 2.3.3 Use modelling and scenarios to inform decision-making

- Lesson 2.4 Be responsive to concerns, clear about intentions and transparent about trade-offs

- 2.4.1 Engage stakeholders, partners and the public in key decisions, to the extent possible in the circumstances

- 2.4.2 Be transparent about how different considerations have been weighed against one another.

- 2.4.3 Clearly signal in advance where the response is heading, to help people navigate periods of uncertainty and transition.

Overview

Good pandemic decision-making must be responsive to changing circumstances and take account of cumulative effects.

In the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Government made many hard decisions (such as imposing border restrictions and quarantine requirements) quickly and under pressure. The elimination strategy, once adopted, provided a clear purpose and touchstone for such urgent decisions. However, as the pandemic wore on – especially in the second half of 2021 – the goal of (re)eliminating community transmission began to move out of reach. This made pandemic decision-making more challenging, especially because there had been limited capacity to consider and plan for other options and scenarios (including how to move on from a zero-transmission target).

Good pandemic decision-making must be responsive to changing circumstances and take account of cumulative effects. In a future pandemic, it will be important for decision-makers to keep sight of the overall purpose of the response, while also having a degree of flexibility about how this is achieved.

Depending on the situation and context, the decisions necessary to look after all aspects of people’s lives may need to shift over the course of a pandemic response. For example, the kinds of actions taken in a situation where no vaccine is available will differ from those required in a situation in which nearly everyone is fully vaccinated. Good decision-making processes that can anticipate and accommodate a changing context, lead discussions with the public to keep them abreast of likely scenarios, and maintain focus on people’s economic, social and cultural interests become crucial in such situations.

Depending on the situation and context, the decisions necessary to look after all aspects of people’s lives may need to shift over the course of a pandemic response.

The role of a lessons-focused Inquiry such as ours is not to stipulate exactly what decisions should be made in a pandemic (either in the now-past COVID-19 pandemic, or in any future pandemics). Rather, our role is to identify factors and processes that will ensure strong options and robust analysis and advice are available to future decision-makers.

A critical tool in the pandemic decision-making toolkit is identifying and planning for a range of likely pandemic scenarios.-This can support good decision-making before a pandemic by helping governments prioritise investment to manage the most likely pandemic-related risks (discussed further in Lesson 6), and during a pandemic by helping decision-makers predict how the pandemic may evolve and plan for changes or transitions in the response. It can also be used to estimate the impact of different measures or policy responses at specific points in the pandemic, helping decision-makers evaluate different options and their likely benefits and harms.

Lesson 2.1 Maintain a focus on looking after all aspects of people’s lives in pandemic preparedness and response

Consider and plan for multiple time horizons simultaneously

At the start of any future pandemic, decision-makers will need to react to the immediate threat and do whatever is necessary to protect people from imminent harm. At the same time, however, they should ensure that planning for the longer term – including for the recovery phase – gets underway as soon as possible. Without this dual focus on both the immediate situation and the longer-term picture, there is a risk that the response remains in a reactive mode for too long, or fails to effectively identify, anticipate or mitigate wider impacts.

An effective pandemic response requires dedicated, future-focused planning to be carried out separately from (but in parallel with) the immediate operational response. Our ‘Looking Back’ analysis suggests that a separate strategic function responsible for keeping the evolving ‘big picture’ in mind as the COVID-19 pandemic evolved would have strengthened Aotearoa New Zealand’s response. This needs to be staffed by people with the right skills and attributes – preferably identified in advance.

An effective pandemic response required dedicated future focused planning to be carried out separately from (but in parallel with) the immediate operational response.

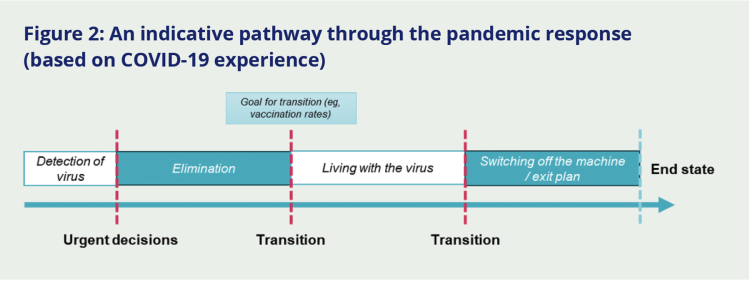

Both before and during a future pandemic, there may be value in mapping out the overall pathway the Government expects to follow in managing the response. Achieving the goals of the response is likely to involve several distinct phases, each with its own strategy and specific aims. Mapping the likely stages on this pathway ahead of time may help decision-makers to prepare to transition between response phases. Such mapping could also help to identify potential indicators or targets that might trigger a change in strategy (see Figure 2 for an indicative example for COVID-19), and help the public, stakeholders and experts to understand the overall direction of the response and prepare accordingly.

Of course, such mapping needs to be alive to the possibility that the anticipated trajectory of the pandemic may change – due (for instance) to changes in the pathogen, shifts in public compliance with control measures, or the early, late or unexpected arrival of a new tool to combat the virus. In Aotearoa New Zealand’s COVID-19 response, for example, the Government had to adapt its strategy when it became apparent that the Delta variant was unlikely to be eliminated. Continually adjusted scenario planning will help the strategic part of the response consider and plan for the medium- and long-term time horizon.

Figure 2: An indicative pathway through the pandemic response (based on COVID-19 experience)

Make more explicit use of ethical frameworks to balance different rights, values and impacts over time

In our view, Aotearoa New Zealand’s leaders generally did well at juggling the ethical complexities during the COVID-19 response. It was clear from our engagements and evidence that ministers and officials were aware when ethical principles were at play and took a thoughtful approach to considering and balancing them. However, it seems the use of ethical principles to inform decisions during the COVID-19 response was largely intuitive.

We think there is value in making more explicit use of ethical principles that can consistently and transparently guide decision-makers. These principles could be applied at all levels of the response – from the allocation of clinical resources to individual cases, through to Cabinet level decisions about prioritising vaccination rollouts, or balancing public health measures, such as lockdowns, against their wider impacts. While the same principles apply to both pandemic planning and pandemic response, the relative importance of each principle may shift. For instance, greater weight may be placed on protecting health and wellbeing in the early stages where there is less information about the virus.

It is generally much easier for people to accept difficult decisions when they understand (or even endorse) the principles and values that sit behind them and see how they have been used to arrive at a decision. As the World Health Organization (WHO) has commented, without such discussion response efforts could be hampered:

“A publicly-discussed ethical framework is essential to maintain public trust, promote compliance, and minimize social disruption and economic loss. As these questions are particularly difficult, and there will be insufficient time to address them effectively once a pandemic occurs, countries must discuss them now while there is still time for careful deliberations.”9

Several existing ethics frameworks have been specifically designed for this purpose. One of the most globally influential is promoted in the Oxford Handbook of Public Health Policy.10 Based on a Canadian model,vi the guiding values from this framework are intended to be useful in any jurisdiction. As this was published pre-COVID-19, and has a strong focus on healthcare settings, it is likely that it will soon be updated to reflect learnings from COVID-19, including the much wider range of impacts a pandemic can have. This approach distinguishes between substantive values (values that guide what decisions are made during a pandemic) and procedural values (values that guide how decisions are made during a pandemic).

Table 1: Values to guide ethical decision-making in a pandemic

| Substantive values (values that guide what decisions are made in a pandemic) | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Procedural values (values that guide how decisions are made during a pandemic) | |

|

|

Source: Based on Oxford Handbook of Public Health Policy, 2019 and University of Toronto Joint Centre for Bioethics, 2005, A report of the University of Toronto Joint Centre for Bioethics Pandemic Influenza Working Group, https://jcb.utoronto.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/stand_on_guard.pdf

In 2007, the National Ethics Advisory Committee had also published a set of ethical guidelines for epidemics and pandemics for use in Aotearoa New Zealand.11 After COVID-19, the National Ethics Advisory Committee began updating its pandemic guidance, holding extensive public consultations in 2022.12 There was strong support for a pandemic response that prioritised people’s health and wellbeing, and moderate support for efforts to protect the most vulnerable – including by providing greater support to those with greater needs (such as disabled people, older people and Māori). Submissions highlighted the public’s strong expectation that, in a pandemic, freedoms should be protected as much as possible, and the Government should justify the use of restrictive measures. Responses also emphasised the importance of transparent decision-making and clear communication about the principles and evidence used in making decisions.

The National Ethics Advisory Committee’s guiding principles for a pandemic (shown in Figure 3) are specific to Aotearoa New Zealand and offer localised and culturally relevant guidance. At the time this report was completed, an updated (post-consultation) version of the Committee’s pandemic guidance was due to be published (Figure 3 reflects this latest version).

Figure 3: National Ethics Advisory Committee’s updated guiding principles for an epidemic or pandemic

| Manaakitanga: implementing measures that are intentioned, respectful, and demonstrate caring for others. Establishing mutually beneficial communication and collaboration pathways. |

| Tika: implementing measures that are ‘right’ and ‘good’ for a particular situation, through being open and transparent. Cultivating trust between decision-makers and the people they impact. |

| Liberty: implementing measures that uphold human rights, including liberty and privacy. |

| Equity: implementing measures that eliminate or reduce unjust inequities in health outcomes for different groups of people and achieve Pae Ora for all. |

| Kotahitanga: implementing measures that strengthen social cohesion through empowering local government, leaders and communities to be active participants in the planning and response. |

| Promoting health and wellbeing: implementing measures that protect and uplift the four cornerstones of Te Whare Tapa Whā health model: whānau health, mental health, physical health and spiritual health. Healthy individuals and whānau turn into healthy communities and a healthy population. |

Source: Based on information from the National Ethics Advisory Committee (Ministry of Health), 2022, Ethical Guidance for a Pandemic (Draft report) https://neac.health.govt.nz/

Both the Oxford Handbook and the New Zealand frameworks set out core valuesand principles that can guide decision-makers towards a people-centred pandemic response. It is important that the principles and processes used by decision-makers during the crisis are visible to the public, both before the next pandemic for discussion and input, and during the next pandemic as a framework to progress decisions. It will be important for future governments to regularly engage with the public about what it is that they value, to ensure that decision-makers explicitly consider and communicate these trade-offs in an empathetic and accessible manner.

Lesson 2.2 Follow robust decision-making processes (to the extent possible during a pandemic)

An emergency response often requires decisions to be made quickly and with limited information or consultation. Normal decision-making processes may need to be modified, abbreviated or (in situations of extreme urgency) temporarily set aside to enable a rapid response. For example, in urgently deciding to introduce very tight border restrictions to prevent or exclude the arrival of a new pandemic agent, decision-makers may need to act without receiving comprehensive advice on alternative options or hearing from a broad range of stakeholders.

But there are risks to suspending these processes, and these risks increase over time. Without comprehensive advice and consideration of diverse perspectives, decision-makers may become overly focused on a particular set of objectives.

They may also be less aware of changing public concerns and expectations, or the unanticipated consequences of the decisions they make. This narrowing in focus and awareness is often referred to as ‘group think’ – a situation in which alternative options or important evidence may be overlooked.

Whenever possible more comprehensive consultation, advice and discussion should be brought to bear in decision-making.

A key lesson from the COVID-19 response is therefore the importance of following robust decision-making processes and actively encouraging the expression of diverse points of view, to the extent that circumstances and time allow. When decisions must be made quickly, the range of processes and tools will be limited to those that can be employed by a small group of decision-makers and advisors. Whenever possible, however, more comprehensive consultation, advice and discussion should be brought to bear. What this looks like will depend on the urgency of the situation and is likely to require a degree of pragmatism. But decision-makers must be aware there may be a trade-off between speed and robustness. More comprehensive consultation and advice takes time, but also protects against the risks of poor decision-making, group think and loss of social licence.

While they may sometimes feel slow, the decision-making processes normally followed within Government – including the time needed for comprehensive consultation and the development of advice – are designed to support good decisions. They should be truncated during a crisis only to the extent necessary, and resumed as early and fully as possible to ensure decision-makers have the best advice to inform their decisions.

Seek out a range of advice and perspectives

While the breadth of input will be determined by the time available, Governments should still seek out advice and perspectives on what is happening, what might happen and how they might adjust their approach to meet changing pandemic circumstances. It is important to create a culture where both advisors and decision-makers feel empowered to contest the advice and present different views on how to achieve the best outcomes.

In both preparing for and responding to a future pandemic, decision-makers (and their advisers) should therefore actively seek out:

- Advice from different public sector agencies, including local government, on policy options for dealing with a range of plausible scenarios.

- Data and intelligence (including emerging scientific evidence, modelling, qualitative and quantitative data, and international experience and insights).

- Wide-ranging expertise from many disciplines and sectors – biomedicine, science, economics, behavioural and social sciences, Te Ao Māori, businesses, human rights organisations and more.

- Input from stakeholders and key partners, including iwi and Māori and other community groups who play key roles in designing, operationalising and delivering the response.

- Public opinion data which tracks people’s attitudes to the pandemic and response and indicates how they may respond to future decisions.

Make use of times when the situation is stable to look ahead and plan for what might come next

In the early stages of a pandemic response, when little is known about the pandemic pathogen, a precautionary and risk-averse approach is likely to be the most appropriate. But once the immediate threat has been addressed, and as more information becomes available, decision-makers may find some breathing space where they can consider if the initial approach is still appropriate – and what might come next.

Such a breathing space was available to New Zealand decision-makers in mid-2020, when the combined effect of national lockdowns, border restrictions, quarantine requirements and other public health measures eliminated COVID-19 transmission in the community for 100 days. This was a significant opportunity to regroup, take stock and look ahead – but (as set out in Chapter 2) it may not have been used to full effect.

While it is important to keep the possibility of changing scenarios in mind all the time, in a future pandemic, decision-makers should be alert to opportunities presented by periods of relative stability and ensure they are used well. At these times, decision-makers have more opportunity to take in the ‘big picture’, and review the medium- to long-term strategy to check that the response is still on track to achieve its overall goals.

Anticipate and plan for burnout

Throughout our Inquiry, we were constantly reminded of the extraordinary effort and commitment of leaders, officials and others who – under great pressure – set up the initial response to COVID-19 and enabled the success of the elimination strategy. However, they paid a heavy price. As we saw in Chapter 2, the pressure was relentless, the situation was constantly changing, and people were working for long stretches in unfamiliar and sometimes difficult environments. Burnout was common.

Decision-makers should be alert to opportunities presented by periods of relative stability and ensure they are used well.

It is difficult for decision-makers to remain adaptable and innovative – and to juggle managing the day-to-day pandemic response with planning for the next phase – when they are exhausted. Based on our findings, this was one reason why leaders struggled to develop and communicate a forward-looking plan for moving on from the elimination phase, despite the breathing space that opened up in mid-2020 when Aotearoa New Zealand was COVID-19-free.

The next pandemic response is likely to be no less challenging and the demands on decision-makers will be similarly unrelenting. For this reason, it is vital to embed workforce resilience and sustainability, and plan workforce capacity ahead of time.

Lesson 2.3 Use appropriate tools when developing and considering policy response options

The COVID-19 pandemic presented complex and dynamic problems, and the possible policy responses were numerous. For decision-makers in Aotearoa New Zealand and elsewhere, coming up with bespoke policy options under pressure, and then understanding and comparing the costs, benefits and trade-offs between these options was a constant challenge. Much can be done now to ensure this process is easier in the next pandemic.

Identify a wide range of possible policy response options

Having just experienced the COVID-19 pandemic, we expect many agencies will be better prepared with a set of potential response options ahead of a future pandemic. It is important not to be complacent about this, and to ensure that the lessons learned and future policy options developed in response to COVID-19 are well-documented and regularly reviewed and updated. Preparing options for a future pandemic should be part of the ongoing work of all government agencies, including:

- identifying potential policy and response options (for example, are contact tracing, isolation and mask wearing sufficient to eliminate transmission or do we need to impose lockdowns?)

- anticipating design and implementation considerations (for example, how should geographical boundaries be determined and implemented if regional lockdowns are used?)

- considering the potential flow-on implications for other systems (for example, what implications will border restrictions have for New Zealanders overseas, the labour market and supply chains?)

- estimating the potential impacts on people (for example, what are the health benefits of lockdowns versus the impacts on other aspects of people’s lives – employment, relationships, education, mental health?), and

- identifying potential vulnerabilities and gaps that should also be addressed (for example, how will supply chains for essential medicines and products be maintained in the context of dramatically limited global transportation?).

This work should draw from a range of policy tools and frameworks, including human rights frameworks and te Tiriti o Waitangi. It is important to prepare options with reference to multiple potential pandemic scenarios (considering factors related to the pathogen, as well as economic and social factors), to test how they may perform under different circumstances.

Compare the impacts of different policy response options to make good decisions

With a clear and comprehensive list of options available, it is important to then consider the relative impacts of each option against the goals sought – just like any other business case. Two common tools for systematically weighing up the costs and benefits of different options are:

- Cost Benefit Analysis (CBA) which offers a structured approach to evaluate the economic pros and cons of various options. By quantifying benefits and costs, it supports informed decisions to achieve agreed objectives.

- Multi-Criteria Analysis (MCA) which can accommodate a wider range of criteria, making it suitable for complex decisions involving diverse factors. This method can help to make trade-offs between the different visible outcomes and support options being explicitly assessed against ethical principles.

These tools – and others – can support decision-makers to select optimal combinations of policies by weighing the financial investment in a policy against its likely success at reducing harmful impacts of the pandemic, while also considering the risk of new or ‘unintended’ consequences of the policy itself. Such tools require good data inputs and integrated epidemiological, social and economic modelling alongside expert analysis and advice on qualitative aspects like the impact on people’s freedom and human rights, or likely outcomes for specific groups.

Spotlight: Making complex decisions in a pandemic | Te whakatau tikanga matatini i tētahi mate urutā

While more than 80 percent of people in Aotearoa New Zealand had received two doses of the COVID-19 vaccine by November 2021, it was known that protection from vaccination generally waned over time.

Cabinet was therefore asked to consider rolling out COVID-19 booster doses alongside the continuing drive to get more people to have the initial course. Since the pandemic began, the Government had been clear that maximising vaccine uptake was essential to allow the country to move on from repeated lockdowns and stringent public health measures.

Ministers had to weigh up multiple factors – including the cost of administering additional doses, evidence of booster effectiveness, whether requiring the vaccination programme to roll out booster doses might detract from its efforts to maximise overall vaccination coverage, and the possibility that new COVID-19 variants might emerge just as the country was beginning to open up. Ministers were also conscious that Māori and Pacific people had lower vaccination coverage and were at higher risk of severe COVID-19 disease compared with other groups.

Cabinet received advice from the Ministry of Health, the Treasury, and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade on the complex factors they needed to weigh up. The advice included explicit consideration of vaccine supply issues and of the implications for Māori, children and young people and older people if boosters were rolled out.

Cabinet ultimately decided to proceed with a targeted booster rollout which prioritised those at highest risk of exposure and illness (including health workers, everyone aged 65 years or over, Māori and Pacific people aged 50 years or over, and people especially at risk from the virus due to other health conditions). It began in late November 2021. The booster rollout accelerated in the new year as Omicron got closer, with the required time to wait between having the second dose and the booster reducing to five months, and then four months, and becoming available to a wider age range. This successful booster rollout ensured those groups most vulnerable to the virus had high levels of protection when the country’s first substantive COVID-19 ‘wave’ arrived in March 2022. This probably saved hundreds of lives and reduced pressure on the health system.

This example illustrates many of the elements of good decision-making we consider essential in the next pandemic response:

- Leaders remained committed to the objective of maximising vaccine-related protection while adapting how this was achieved as the situation changed.

- With support from advisors, they reviewed evolving evidence (on levels of primary vaccination, the duration of protection and groups at greater risk from COVID-19 infection) and weighed up potentially competing objectives (maximising overall population coverage, compared with optimising protection for the most vulnerable).

- While the extent of broader consultation is unclear, as is the use of tools such as cost-benefit analysis, input was sought from several government agencies and explicit attention was paid to the needs of particular groups.

- Finally, the decision to proceed with the booster programme, and the reasons for it, were communicated to the public clearly and transparently.

Use modelling and scenarios to inform decision-making

While modelling is a useful input, it is not a panacea for selecting optimal policy responses.

Modelling and scenario thinking can be particularly useful tools to support good decision-making in a pandemic response. Indeed, they will likely be essential to underpin the tasks set out in this lesson. Modelling can be used to indicate how key indicators (such as rates of infection or hospitalisations) are likely to evolve in response to specific interventions or policy options, helping decision-makers evaluate different options and weigh up the trade-offs involved. The World Bank, OECD and WHO have all recently emphasised the importance of modelling that integrates epidemiology, health and economic domains as part of future pandemic preparedness.13

Modelling was a useful input in many key decisions during Aotearoa New Zealand’s COVID-19 response. Modelled projections of COVID-19’s health impacts under different approaches were a key catalyst for the initial decision to ‘close the border’ and place the country in lockdown, while later decisions about moving up and down alert levels were also informed by modelling. The Inquiry heard that modelling evidence was particularly helpful when it combined projected impacts across multiple domains (for example, economic as well as health indicators). The potential uses of modelling are also expanding rapidly as technology advances, making it faster and easier to test sensitivity to different inputs.

While modelling is a useful input, it is not a panacea for selecting optimal policy responses. Models rely on assumptions about the impact of particular measures and can only give an approximation or estimate of what may happen if they are implemented. Moreover – and especially in the context of a pandemic – the sheer complexity of many policy options and their associated trade-offs cannot be captured in a single quantitative framework. It is therefore important that modelling is treated as a guide and considered alongside other inputs, including the views of key partners, stakeholders, experts and the wider public.

Spotlight example: Responding to changes in risk and vaccine-related protection | Te urupare ki ngā huringa o te mōrea me te ārai ā-rongoā āraimate

A key consideration in any pandemic response is the availability and impact of vaccines.

Based on experience with COVID-19, vaccination rates are likely to be an important consideration in decisions about if and when to use and/or relax strict measures such as lockdowns. But it will be critical to monitor emerging scientific evidence on the effectiveness of vaccination, especially if the pandemic pathogen mutates frequently and/or protection from vaccination wanes over time (as was the case with COVID-19 on both counts).

In situations where the protection from vaccination does wane over time, it is not vaccine coverage that should be the ‘target’ for when to loosen public health measures, but the estimated immunity in the population (see Appendix D). As such evidence on waning emerges, it should be factored into any modelling alongside other variables as soon as possible.

Time lags also matter for decisions about when to introduce or stand down public health restrictions. Experience during COVID-19 in a range of jurisdictions is that it can take several weeks – if not months – for a new epidemic wave to gain momentum after restrictions are relaxed.

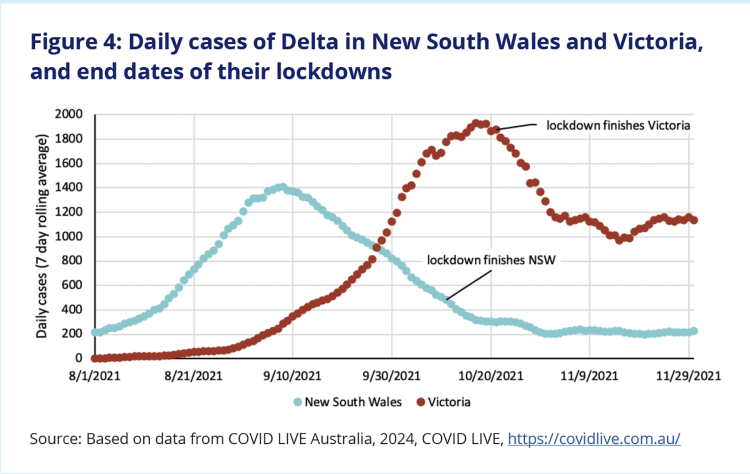

While information about vaccination levels often informed decisions about when to end stringent COVID-19 public health measures, different jurisdictions used this information in different ways. In Australia, for example, the states of New South Wales (NSW) and Victoria both moved out of lockdowns when their populations reached 70 percent vaccination coverage on 11 and 22 October 2022, respectively14 – about six weeks before the Auckland Delta lockdown ended. Daily case numbers for Victoria and NSW are shown in Figure 4, and demonstrate that case numbers did not surge following the lifting of restrictions.

Figure 4: Daily cases of Delta in New South Wales and Victoria, and end dates of their lockdowns

Source: Based on data from COVID LIVE Australia, 2024, COVID LIVE, https://covidlive.com.au/

Deciding when to relax public health restrictions is a delicate balancing act. The experiences in New South Wales and Victoria suggest it is possible to remove lockdown restrictions before completing a vaccination rollout without this leading to an immediate resurgence of cases. While there is some risk involved with lifting lockdowns at lower levels of vaccine coverage, relying on a lag in case rate resurgence to ‘bridge over’ to higher vaccination coverages is something that could be considered in a future pandemic response. Appendix D provides further analysis of how consideration of such factors could provide evidence to support decisions about lifting stringent public health measures in future.

Lesson 2.4: Be responsive to concerns, clear about intentions and transparent about trade-offs

While an effective pandemic response requires strong leadership, it also requires a high degree of confidence and trust in public institutions and decision-makers from the general public, Māori, communities of all kinds, businesses, and key partners and stakeholders the Government works with. Decision-makers are more likely to retain this kind of confidence and trust when the reasoning behind their decisions is transparent and clearly communicated, when their decisions are open to scrutiny and debate, and when they demonstrate willingness to revisit and (if necessary) modify decisions as circumstances change. It is important for people to see leaders being responsive to their needs, concerns and recognising the impact of decisions on people’s health, social, economic and cultural interests.

Engage stakeholders, partners and the public in key decisions, to the extent possible in the circumstances

As COVID-19 demonstrated, opportunities for direct discussion are often limited during a pandemic for logistical reasons. This makes it more difficult and time-consuming for government to undertake meaningful engagement with stakeholders, partners and the public. While urgent pandemic decisions can (and often should) be made quickly without broad consultation or engagement, in the longer-term this approach can create the impression that decision-makers are unaware of – or unresponsive to – people’s concerns. It also increases the risk that decision-makers and advisers may misread public sentiment, underestimate the strength of feeling around particular issues, or lapse into ‘group think’.

Taking time to engage the public, Māori, communities, businesses and key partners ensures decision-makers are aware of important concerns and receptive to suggestions about how they might be addressed. It also helps build trust in government and can support better public understanding of the need for decision-makers to balance potentially competing objectives or values. This is likely to be particularly important in a pandemic, when the needs and priorities of different groups must sometimes be explicitly weighed against each another.

Meaningful engagement is more likely to occur when the Government has already built relationships and processes for dialogue. Decision-makers and advisors should draw on these established connections as much as possible to support decision-making in a pandemic. Lesson 5 explores wider lessons about working together with Māori, communities and business to achieve shared goals.

Aotearoa New Zealand’s COVID-19 experience showed that when decisions need to be made quickly, pre-existing approaches to engagement might not be suitable. In such instances, it may be necessary to develop more rapid and pragmatic forms of engagement such as the creation of advisory panels (including representatives from relevant groups). In periods of greater stability, more comprehensive forms of engagement should be undertaken ahead of major decisions, such as changes in public health strategy and longer-term recovery options.

In our engagements with groups who felt alienated by the Government’s response, or who had major concerns with some of the approaches taken during COVID-19, we encountered a wide range of views and some common themes. Some of the points raised with us seemed reasonable (such as calls for greater consideration of and engagement with New Zealanders finding it difficult to return home). In future situations, there could be opportunities to avoid or mitigate some of these concerns.

More direct government engagement with groups voicing disquiet at aspects of the response would be valuable during a future pandemic. Perspectives should be listened to openly as this can help with weighing up the benefits and harms of policy options.

In our view, some more direct government engagement with groups voicing disquiet at aspects of the response would be valuable during a future pandemic. Perspectives should be listened to openly as this can help with weighing up the benefits and harms of policy options. Even when agreement cannot be reached about the preferred overall policy response, such engagement can give people confidence that their point of view or opposing position has at least been listened to, and that their concerns are being considered when weighing up trade-offs as part of the decision-making process. This can in turn reinforce and support social cohesion to some degree. However, such engagements should be carefully considered on a case-by-case basis – we are not advocating that busy leaders should meet with groups that have no real interest in being constructive.

In other jurisdictions, innovative approaches such as citizens’ juries and other deliberative formats are being used to engage members of the public on complex policy issues. Ireland, for example, uses Citizens’ Assemblies to help the government address important challenges. Approaches like these can allow decision-makers to take account of public views and values when assessing options and considering trade-offs.15 However, they take considerable time (including for preparing and selecting participants) and for this reason are unlikely to be feasible during the emergency phase of a pandemic response. As part of the Government’s preparation for a pandemic, such approaches could offer useful insights into how the public want their leaders to make decisions in an emergency.

Be transparent about how different considerations have been weighed against one another

During the COVID-19 response, governments around the world had to repeatedly weigh up different objectives and values, and then judge how best to balance them. This was especially important when making decisions that placed constraints on people’s human rights (such as restricting the return of citizens from overseas, limiting domestic movement, and using vaccine mandates). In Aotearoa New Zealand – as in other countries16 – the judgements underpinning these decisions were not always made public (or done so explicitly and with clarity). This meant people did not always understand why particular decisions were made, or how introducing or removing measures might affect the risks facing specific groups.

COVID-19 showed us that governments need to be willing to share information with the public, however difficult or uncomfortable, in order to retain their trust in government, public institutions and the response.

Decision-makers often had good reasons for not wanting to advertise how they were choosing to balance different priorities in the COVID-19 response. For example, the decision to protect Pacific communities and Māori – who were at greater risk from the Delta variant – was a key factor in the decision to maintain the Auckland lockdown in late 2021; however, leaders were reluctant to make this reasoning public in case of a public backlash against these communities. But deciding not to share the reasons behind such decisions came at a cost. Over time, some people lost trust in the Government or felt it didn’t care about the harm caused by restrictive public health and social measures. Others started to feel the Government was withholding information from them or making decisions based on a hidden agenda.

COVID-19 showed us that governments need to be willing to share information with the public, however difficult or uncomfortable, in order to retain their trust in government, public institutions and the response. This means being upfront with people about the level of risk different groups may face, and why this may influence certain trade-offs. It also means acknowledging that decisions may change or be reversed as the situation evolves and relevant trade-offs are revisited. In the longer term, it is essential for maintaining social licence as the response, and the process of balancing objectives and risks, continues to evolve.

Clearly signal in advance where the response is heading, to help people navigate periods of uncertainty and transition

Experience with COVID-19 – in Aotearoa New Zealand and elsewhere – shows how challenging it is for leaders to retain public confidence through difficult transitions in the pandemic response. While such transitions and changes of direction due to new events – such as a new variant – cannot be avoided, it is easier to retain people’s confidence when they have had prior warning and understand why they are necessary. Failure to do so risks undermining people’s confidence in government in the longer term.

It is important that, at regular intervals, leaders describe their long-term response plans and the steps they anticipate as the country moves towards a new post-pandemic ‘normal’. This involves being honest about the challenges to be navigated in likely future phases of the response (such as learning to live with the virus), and proactively outlining new scenarios that might arise. While noting their intention to carefully plan and manage the transition between these phases, leaders should be clear that the exact timing will depend on many factors and will therefore require a degree of flexibility.

Communicating changes in direction during a pandemic response can be difficult. This is especially true if they involve reintroducing restrictive measures such as lockdowns, or accepting risks that were previously presented as unacceptable. But despite the communication challenges, it is important that leaders move quickly to change direction when circumstances require it. Being transparent about the rationale for a change will help people accept and support it, as will explaining that – even though some may experience temporary hardship or inconvenience as a result – the decision will ultimately support the overall goal of the response: looking after all aspects of people’s lives as much as possible.

Lesson 3: Build resilience in the health system | Akoranga 3: Te whakatipu kia tū pakari te pūnaha hauora

In brief: What we learned for the future about building resilience in the health system

In preparing for and responding to the next pandemic:

- Lesson 3.1 Build public health capacity to increase the range of options available to decision-makers in a pandemic. In practice, this means:

- 3.1.1 Make scaling-up effective testing and contact tracing part of core public health capability

- 3.1.2 Plan for a flexible range of quarantine and isolation options

- 3.1.3 Be ready to quickly implement infection prevention and control measures

- Lesson 3.2 Enhance the health system’s capacity to respond to a pandemic without compromising access to health services. In practice, this means:

- 3.2.1 Build the capability of the healthcare workforce

- 3.2.2 Strengthen intelligence, monitoring and coordination of healthcare to enable adaptability

- 3.2.3 Improve health system infrastructure

- 3.2.4 Strengthen resilience in primary healthcare

Overview

Before COVID-19, Aotearoa New Zealand’s public health system was assessed as moderately well-prepared for a pandemic. With the arrival of the virus, however, it became clear that greater public health capacity was needed. Thanks to impressive effort and innovation, key tools such as contact tracing and testing were quickly scaled-up. But capacity limits remained a challenge, and systems for large-scale isolation and quarantine had to be developed from scratch.

Aotearoa New Zealand’s health system was never overwhelmed by COVID-19, thanks to the success of the elimination strategy (and a degree of good luck). However, the pandemic highlighted and exacerbated the health system’s underlying fragility, with long-standing capacity constraints affecting core areas, including workforce, physical infrastructure, supply chains. These long-standing and underlying issues should be addressed before the next pandemic, as much as it is possible to do so.

A key aspect of pandemic preparation is to build resilience into Aotearoa New Zealand’s health system. The OECD describes resilience as:

“the ability of systems to prepare for, absorb, recover from, and adapt to major shocks. It is not simply about minimising risk and avoiding shocks: resilience is also about recognising that shocks will happen.”17

Having better public health capacity will enable a rapid initial response to any future pandemic, increasing the likelihood that the pandemic virus (or other infectious agent) can be excluded or eliminated before it becomes established. The ability to rapidly scale-up key public health functions such as contact tracing will also give decision-makers more options, potentially reducing the need to use blunt measures like lockdowns.

A resilient health system is one equipped with a strong workforce, secure supply chains (including for medicines and medical equipment) and good infection prevention and control processes (which require well-maintained stocks of PPE and excellent ventilation systems). Having these resources in place before a pandemic arrives will better enable the health system to continue meeting other health needs during a pandemic response, ensuring support for all aspects of people’s health.

Lesson 3.1: Build public health capacity to increase the range of options available to decision-makers in a pandemic

COVID-19 demonstrated the importance of core public health functions such as testing and contact tracing, isolation and quarantine, and infection prevention and control measures. These will provide the first line of defence in the next pandemic, preventing or slowing transmission of the virus and protecting people from serious illness and death.

Importantly, the greater the capacity to deliver these tools and functions (especially at the start of a pandemic), the more options decision-makers will have at their disposal. For example, if testing and tracing systems are ready to be rapidly scaled-up when the first cases of a new pandemic disease are detected, it may be possible to eliminate chains of transmission without the need for national lockdowns. Higher uptake of infection control measures (such as masks) in public spaces may also reduce the need to restrict people’s movement.

The public health response to a pandemic is interconnected with its economic and social impacts. Building public health capacity in key areas can create options for mitigating the health impacts of a pandemic without having to resort to more stringent measures that have high economic and social costs. For example, Taiwan was able to eliminate COVID-19 transmission in 2020 without using lockdowns, due to its well-developed testing and contact-tracing capacity and very high levels of mask wearing in its population.

Of course, even the best-prepared country may need to resort to lockdowns in a future pandemic, and we cannot rule out their use in Aotearoa New Zealand again. However, our analysis of the response to COVID-19 has shown that the need to use more stringent measures such as lockdowns may be reduced by building the capacity and resilience of core public health services and tools.

Make scaling-up effective testing and contact tracing part of core public health capability

Testing and contact tracing are core functions that form part of the day-to-day toolkit used by public health services in Aotearoa New Zealand. In a pandemic response to a pathogen that is amenable to contact tracing, these functions will need to be rapidly expanded to detect and contain new chains of transmission across the population.

For these capabilities to be ‘kept warm’ in case of a future pandemic, planning and investment is needed so they can be rapidly and effectively scaled-up when needed. This includes:

- Investing in the public health workforce, including training and capacity building for the specific skill of contact tracing.

Contact tracing requires a skilled workforce, experience in interacting with members of the public to obtain potentially sensitive information and familiarity with digital record-keeping platforms. COVID-19 showed how contact-tracing capacity can be quickly expanded via recruitment and short-course training of non-public health personnel – but provision of training, oversight and quality control all rely on existing expertise, especially for the core team that will train others. - Enabling public health services to develop and maintain relationships with local communities.

Contact tracing is most effective where public health workers have good relationships with the communities they serve. People can be reluctant to discuss where they have been, and who they have been with, particularly in stressful circumstances such as having been exposed to a virus. Navigating this requires skill on the part of the contact tracers, and trust on the part of those they are speaking with. COVID-19 demonstrated the importance of effective relationships between public health services and the communities they serve – including different ethnic minorities, faith groups, business leaders and Māori. - Maintaining digital platforms, information systems and supporting capability.

The development of effective digital platforms to support contact tracing was one of the successes of the COVID-19 response. It will be important to maintain and strengthen this capacity so that health information can be safely coordinated and shared, both in the context of normal public health activities as well as in a pandemic. Investing in digital and data capacity is a key form of insurance in case of future public health crises. - Establishing mechanisms to facilitate rapid scaling-up of testing capacity.

Testing is an essential complement to contact tracing. It enables people who are infected to be isolated – preventing further spread – and allowing those without infection to go about their daily lives. COVID-19 showed the importance of being able to rapidly scale-up testing capacity but also the difficulties encountered when access to testing is limited. With most of the country’s testing capacity located in private laboratories, it will be important for government to consider how to ensure it has access to additional testing when needed.

Plan for a flexible range of quarantine and isolation options

Border restrictions and quarantine, lockdowns (national and regional) and home isolation were core parts of Aotearoa New Zealand’s response to COVID-19. However, a more flexible range of quarantine and isolation options could give decision-makers more choices for using these measures effectively, while minimising negative impacts – for example, when someone with a right to enter the country struggles to do so because of a shortage of quarantine capacity. Flexible options could include allowing low-risk travellers the possibility of isolating at home, if feasible.

While officials and agencies learned a lot during COVID-19 about how to make hotels work as quarantine facilities, they were not ideal sites for infection control or isolation of community cases. Memoranda of understanding and other arrangements are required to ensure ventilation is of high quality and that facilities can easily be reconfigured to keep cohorts and people separate in hotel facilities. Other options – ranging from a blend of facilities and home-based quarantine, to bespoke facilities and more hospital-level care facilities – should be investigated ahead of the next pandemic so that decision-makers have a flexible range of quarantine and isolation approaches to consider, depending on the nature of the pandemic.

Be ready to quickly implement infection prevention and control measures

Infection control measures such as the use of PPE, masks and physical distancing were often highly effective in responding to COVID-19. However, Aotearoa New Zealand’s ability to use these measures quickly and to good effect was constrained by shortcomings in procurement and distribution systems, infrastructure and information and advisory systems.

These problems were not confined to this country. Globally, the COVID-19 pandemic created both a supply and demand shock for key equipment and materials essential to the response. It created urgent, worldwide demand for things like PPE, tests, medical devices and vaccines, but at the same time, disrupted the national and international supply chains and workforces that provided those goods and services.

As the next pandemic may well be very different from COVID-19, different infection prevention and control measures may be needed. However, some key equipment is always likely to be required – such as PPE – whatever the next pandemic’s characteristics. Ideally, Aotearoa New Zealand would secure, distribute and manage (for example, by rotating) sufficient stocks of such equipment ahead of time so it is ready to use as soon as required.

The need for other equipment and tools such as bespoke tests and specific vaccines cannot be determined in advance as that will be dictated by the specific pathogen. Therefore, ensuring Aotearoa New Zealand has access to what it needs will depend on having established networks of advice and expertise, strong international relationships and good procurement processes in place.

Lesson 3.2: Enhance the health system’s capacity to respond to a pandemic without compromising access to health services

COVID-19 revealed the intense pressure a pandemic can exert on the health system and its resources. It also demonstrated the importance of maintaining non-pandemic health services while simultaneously responding to both the immediate and long-term effects of a virus or other pathogen. Aotearoa New Zealand needs its health and disability system to be sufficiently resilient to meet both of these competing demands.

Building resilience ahead of a pandemic will ensure that, during the response, decision-makers can be more confident in the ability of the health system to cope with the demands placed on it. This gives them more response options, including adopting a different risk tolerance when it comes to using public health measures such as lockdowns and gathering limits. It will also probably provide substantial benefits for non-pandemic health services. What this might mean in practice is addressed further in our recommendations.

Priority areas that should be addressed are:

- Building the capability and flexibility of the workforce so health workers can be more readily redeployed in a pandemic while other health services are kept going.

- Strengthening the systems that allow for services to be prioritised if necessary. This includes the data, intelligence and monitoring systems that enable decision-makers to understand what capacity is available, and the governance and coordination mechanisms needed to make decisions and ensure capacity is utilised as effectively as possible.

- Improving infrastructure so that the health system can continue safely caring for patients during a pandemic (for example, by improving building ventilation and ensuring capacity to separate potentially infectious from non-infectious patients) and can surge additional capacity where needed (for example, by repurposing facilities for pandemic-specific services or by increasing capacity to care for patients needing ventilation).

- Strengthening resilience in primary health care (that is, general practice and community-based care). Discussion of health system capacity often focuses on specialist services such as intensive care and surgery, but primary health care – while less easily measured – is the foundation of the system and the first line of delivery. During the COVID-19 response, primary care was essential in both the vaccine rollout and dispensing antivirals during the Omicron waves, which likely saved many lives. Strengthening the primary health care workforce, data and intelligence systems and other infrastructure, including building design and ventilation, will enhance Aotearoa New Zealand’s ability to respond well to a future pandemic.

Lesson 4: Build resilience in economic and social systems | Akoranga 4: Te whakakaha i te pakaritanga o ngā pūnaha ōhanga me te pāpori

In brief: What we learned for the future about building resilience in the economic and social systems

In preparing for and responding to the next pandemic:

- Lesson 4.1 Foster strong economic foundations. In practice, this means:

- 4.1.1 Continue to build strong relationships between economic agencies

- 4.1.2 Prepare better for economic shocks

- 4.1.3 Strengthen fiscal reserves and maintain fiscal discipline

- Lesson 4.2 Use economic and social support measures to keep ‘normal’ life going as much as possible. In practice, this means:

- 4.2.1 Deploy economic and social measures to support key health measures

- 4.2.2 Design key tools in advance to save time and resources

- 4.2.3 Build on the improvements to social sector contracting and partnership

- 4.2.4 Maintain well-functioning labour markets, including by providing financial support to workers

- Lesson 4.3 Ensure continuous supply of key goods and services. In practice, this means:

- 4.3.1 Build greater resilience into supply chains

- 4.3.2 Maintain food security for a future pandemic

- 4.3.3 Maintain access to government and community services throughout a pandemic

- 4.3.4 Allow the ‘essential’ category to change over time

Overview

The COVID-19 pandemic and associated policy measures impacted all sectors and parts of society, over a prolonged period. This created demands beyond what could be managed via ‘business as usual’. Thanks to extraordinary effort, innovation and investment – and the success of the elimination strategy – Aotearoa New Zealand did not face the kinds of crises experienced in many other countries. But while the country avoided such predicaments as fuel shortages or running out of essential equipment, the stark risks posed by a pandemic (or other emergency that exceeds the limits of essential systems and infrastructure) were very much apparent.

There were also some positive lessons. Overall, Aotearoa New Zealand’s pandemic experience underscored the importance of strong economic and social institutions that have built up reserves and capacity during ‘normal’ times. This gives decision-makers much better options for responding to a crisis. Because Aotearoa New Zealand went into the COVID-19 pandemic in a relatively strong economic position built up over a number of years, the Government was able to provide swift and generous supports that helped with the success of the elimination strategy and protected many people from the pandemic’s worst impacts. Among other things, the Government funded vaccines, provided generous wage and business support subsidies, arranged short-term accommodation support for people who had been homeless or in unstable housing, and ensured air freight capacity was maintained so that time-sensitive and essential goods could still arrive in the country. Where capacity and infrastructure were already in place, it was easier to manage pandemic risk while minimising disruption to essential activities. The reasonably good availability of internet access across most of the country, for example, made it possible for many people to shift to online learning and working.

A resilient economy and social support systems are important to reduce disruptions to normal life as much as possible, during and after a pandemic.

The interconnected nature of people’s economic, social, physical and mental health means resilience in any one area will have benefits in others. A prepared and resilient education system, for example, that enables children and young people to continue to attend school in person as much as possible, will be protective of their mental health and social development. Avoiding or minimising the use of lockdowns will reduce people’s exposure to stress, loneliness and – for some – violence. Ideally, in a future pandemic, better overall preparation will mean decision-makers have more options that reduce the need for more restrictive measures such as lockdowns and school closures.

A resilient economy and social support systems are important to reduce disruptions to ‘normal’ life as much as possible, during and after a pandemic. These sectors provide essential scaffolding of daily life that becomes even more critical – and comes under greater pressure – in times of crisis. Building resilience into this scaffolding is a key part of future pandemic preparedness. While some degree of disruption and adverse impact is inevitable in a large-scale crisis, this can be lessened if core systems and infrastructure are more robust. This can also act as insurance against other types of shocks and stressors.

Lesson 4.1: Foster strong economic foundations

Ensuring the economy is sufficiently resilient to handle major shocks is critical for looking after people through a pandemic. Strong economic foundations and institutions will enable a greater range of options to respond to a future pandemic and reduce the risks of pandemics causing other crises – in the financial sector, for example.

Continue to build strong relationships between economic agencies

The COVID-19 response benefited from the prior existence of strong working relationships between the main economic agencies. These agencies responded promptly and effectively as developments unfolded although – like their overseas counterparts – they were clearly not prepared for the economic implications of an all-of-society crisis on the scale of a global pandemic.

While respecting the Reserve Bank’s independence in the operation of monetary policy and the Treasury’s ability to provide ministers with fiscal and economic advice in reasonable confidence, the two agencies have developed useful forms of collaboration over many years which serve them well in normal times and up to a point proved valuable during the pandemic. We suggest building and strengthening these key relationships, as well as those with other agencies as appropriate, such as the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment, Inland Revenue, the Ministry of Transport and the Financial Markets Authority. Good and well-directed engagement can ensure access to a wider range of data, insights and skills when they are most needed.

Having these agencies work collaboratively on preparing possible economic response options based on different pandemic scenarios would be valuable. This would pick up on and capture accumulated experience gained through past crises (such as the Global Financial Crisis, earthquakes, floods and now COVID-19). As such experiences are documented and developed, they help to build ‘muscle memory’ for effective response design in the future.

Prepare better for economic shocks

Determining the appropriate initial macroeconomic response to a pandemic is extremely challenging. As the COVID-19 experience demonstrated, it is not safe to assume that the economic shock from a pandemic primarily works through demand. The economic shock associated with the advent of COVID-19 has emphasised the importance of developing greater understanding of supply shocks and how to respond to them. In this and other areas, Aotearoa New Zealand is not alone. Both the Reserve Bank and the Treasury have built up their relationships with international counterparts and institutions. Continuing to share information and experience on these matters should help us to understand better how to respond.