4.3 Our assessment Tā mātau arotake

4.3.1 Closing the border and requiring all international arrivals to quarantine/isolate was effective in supporting the elimination strategy

Border controls and quarantine/isolation requirements were two of the four key pillars supporting the Government’s elimination strategy. As we have noted elsewhere, the elimination strategy was highly effective in containing COVID-19 transmission until most of the population was vaccinated. The decision to close the border and require all international arrivals to enter managed quarantine was essential to the success of that initial strategy. Both measures undoubtedly saved lives and reduced the burden on the health system in the critical pre-vaccination period.

While the managed quarantine system was effective in keeping COVID-19 out of Aotearoa New Zealand, there were occasional breaches. In the year to June 2021, researchers identified 10 instances where COVID-19 was transmitted from someone in a quarantine or isolation facility to a border worker or (occasionally) the wider community, and an outbreak occurred. In many cases the exact route of transmission was unclear, but most cases were thought to involve aerosol particles carrying COVID-19 into shared spaces (such as common exercise areas or smoking areas).47 Based on experience in New Zealand and Australia (combined), the researchers estimated the rate of quarantine escape was 5 per 100,000 travellers in the period to June 2021.

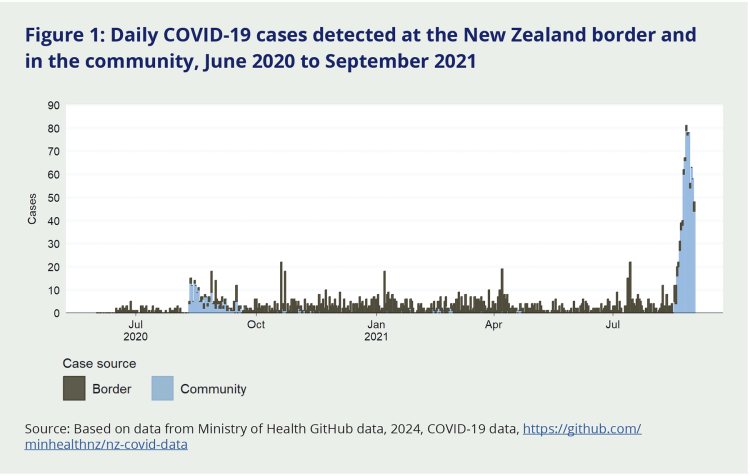

The quarantine system successfully prevented the vast majority of COVID-19 infected travellers from seeding infection into Aotearoa New Zealand. As Figure 1 in this chapter illustrates, a small but steady stream of incoming travellers were COVID-19 positive at the point they entered New Zealand, but the MIQ system successfully prevented these cases from giving rise to COVID-19 transmission in the community.

Figure 1: Daily COVID-19 cases detected at the New Zealand border and in the community, June 2020 to September 2021

Source: Based on data from Ministry of Health GitHub data, 2024, COVID-19 data, https://github.com/minhealthnz/nz-covid-data

Rates of quarantine escape depended on a wide range of factors – such as levels of infection in the countries travellers are coming from, the behaviour of the infectious agent (the transmissibility of COVID-19 variants), duration of quarantine/isolation, characteristics of the quarantine/isolation facility, infection control practices among both travellers and border workers, and vaccination coverage and efficacy in preventing transmission.48 The introduction of additional protective measures provided further safeguards that may have reduced the risk of quarantine breaches. For example, pre-departure testing of people coming to Aotearoa New Zealand from all countries except Australia, Antarctica and most Pacific Islands was introduced in January 2021.49 Vaccination of border workers began in February 2021 and was mandated from May 2021.50

Allowing New Zealanders to return while protecting those already here was a difficult trade-off for the Government to manage. As noted by the authors of the quarantine escape study, ‘The most direct way to substantially reduce the risk of SARS-CoV-2 escaping quarantine [was] to reduce the number of arriving travellers from areas with high infection levels’. But limiting citizens’ return travel raised complex ethical, human rights and legal issues, and created significant distress for those affected (see the ‘Stranded Kiwis’ section). The authors noted that New Zealand’s quarantine escape rate was higher than that in Australia (although numbers were small and the difference was not statistically significant).

They suggested the quarantine escape rate would be lower if quarantine took place in ‘better or purpose-built quarantine facilities in rural locations’, citing the success of Australia’s Howard Springs facility,xiv which had no quarantine escapes.51

The operation of quarantine facilities was costly and required the support of a large workforce – covering transport, hospitality, security, cleaning, catering, health care, operations and logistics. Using hotel facilities (which would otherwise have been largely empty) was more cost-efficient initially than building bespoke quarantine facilities, while the location of hotel facilities near Aotearoa New Zealand’s international airports had practical advantages.

In our lessons for the future and recommendations, we return to what this means for the development of quarantine and isolation options for a future pandemic.

4.3.2 However, the social, economic and personal costs of the border restrictions and quarantine requirements were very high

While border controls and quarantine and isolation requirements were an essential part of the elimination strategy, we saw evidence that the social, economic and personal costs of these measures were very high. Describing the initial border closure in March 2020, senior managers at Auckland Airport told us of ‘a massive financial and operational impact on the airport. We spent the first few weeks working out whether we had a viable business.’ A submission from the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists addressed impacts of a different kind:

“Border restrictions and the Managed Isolation and Quarantine (MIQ) system caused psychological distress … New Zealanders had no certainty about when they would be able to return home... Some groups experienced lasting distress and trauma due to not being able to come home or leave with certainty of being able to return.”

For those who had found themselves on the ‘wrong’ side of the border, two years later it was still hard ‘to get across how deeply the experience of feeling abandoned and cut off’ had affected them, a spokesperson for Grounded Kiwis (a group representing New Zealanders overseas trying to return during the pandemic) told us. Similar feelings were expressed in public submissions; one submitter, unable to see her two daughters for 18 months due to international border restrictions, reflected that: ‘As much as I would like to forget the trauma, it’s simply not possible – this is time that we can never get back and has changed us individually and changed our dynamics as a whānau.’ Other submissions highlighted the plight of international students who were isolated from their families or from their New Zealand universities (if they were offshore when the border ‘closed’). Some experienced financial hardship and deteriorating health and wellbeing, adding to the pressure on New Zealand’s health system.

In drawing attention to such adverse impacts, we recognise that closing the international border and setting up a nation-wide managed system for quarantine and isolation were extraordinary undertakings – unprecedented, and indeed almost unimaginable before March 2020. The fact that these measures were implemented so swiftly, and provided such a robust line of defence during the elimination phase, is commendable. We acknowledge the hard work of all the agencies, sector groups, businesses and workers who made those achievements possible. As Auckland Airport management said of their employees: ‘There was a lot of goodwill with our staff. They were very willing to work long hours to “keep New Zealand open”.’

4.3.3 Decisions about closing and managing the borders were made at speed and policy-makers did not always understand the operational implications. This created challenges and frustrations for those putting decisions into practice

As we have already described, the decision to close the border on 19 March 2020 was made very quickly. Putting it into effect was time critical and operationally complex, requiring coordination and cooperation between multiple government agencies, airlines, airports, port and shipping companies and others. Given the pace at which change was occurring, communication between government, agencies and businesses was not always clear, adding considerable confusion and uncertainty. At Aotearoa New Zealand’s busiest airport, Auckland, the hours leading up to the closure were frantic:

“We did not know what flights were in the air or were scheduled to be in the air when the border closure came into effect. Singapore was asking us whether a particular flight should be boarded or not, given New Zealand’s border restrictions. We should have said, “Don’t board because the border will be closed …” … Instead, we said that the legislation is being reviewed, so go ahead and board, which they did. They arrived and had to fly right back. … Singapore Airline staff on the ground were calling us because they could not get hold of anyone from the Government. So, we were coordinating a three-way conversation between Singapore Airlines, the NZ Government (through the Ministry of Transport), and the Auckland Airport. The Ministry of Transport was trying to talk with other government departments, to clarify the situation.”

The need for speed and agility did not abate. For the next two years, border arrangements continued to be monitored and rapidly adjusted as the pandemic changed course, locally and overseas: between January 2021 and October 2022, for example, around 58 changes were made to air border settings alone. While it was positive that rules were adjusted in response to changing circumstances, agencies have also told us it was a challenge to manage the many regulatory instruments (statutes, orders and more) that supported the border settings, which they said ‘grew in complexity as the duration of the pandemic extended’.

Throughout, officials from the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment engaged with the New Zealand Council of Trade Unions and Business New Zealand on a range of topics. The Ministry also worked with peak sector bodies (such as Retail New Zealand, the Employers and Manufacturers Association, Hospitality New Zealand) and key businesses to support good communications and resolve any emerging issues. Despite these efforts, however, we also heard that the private sector felt it had few avenues for contributing its expertise, leaving some businesses feeling ‘disempowered and frustrated’.

The fast-moving environment sometimes meant that policies were introduced without sufficient consultation with the operational agencies responsible for putting them into effect, leading to difficulties on the ground. We heard specific criticism that health officials did not always appreciate the operational complexities their decisions created at the border. For example, there was some variation in how ships and shipping companies were treated across different ports. While acting on the same Ministry of Health guidance, local medical officers of health could implement this differently depending on their local port’s preferred response to risk.

Health New Zealand | Te Whatu Ora, when it reviewed its role in the MIQ system in 2022, acknowledged its decision-making processes were affected by capacity constraints, the constant need for speed, and the fact they were working in essentially uncharted territory. It is important to acknowledge that, even if health officials are not experts when it comes to managing the border, infection control and health system expertise will remain essential when decisions are made about using border restrictions in another pandemic. That expertise is vital if those restrictions are to successfully prevent the virus from spreading within quarantine facilities and escaping into the community. We will return to this in our lessons for the future in Part 3.

4.3.4 The border exceptions process evolved in response to changing needs as the pandemic wore on, while the lack of integration between MIQ and visa processes was very difficult for travellers

With the border closed to everyone except citizens and residents, an exceptions process was needed to allow non-New Zealanders who had legitimate needs to enter Aotearoa New Zealand. The list of exceptions was extended as the pandemic continued and as worker shortages, which could be tolerated for a short time, became more problematic. For example, seasonal workers from the Pacific were allowed into the country to fill labour shortages in the horticultural and wine-growing sectors. Exceptions were also granted to critical health workers (and their dependants), specialist agricultural operators for harvesting and processing of crops, veterinarians and many more.52 The parameters and criteria for exceptions evolved over time based on changing needs and experience.

By the beginning of August 2022, 39,690 workers had been approved a visa under a border exception, and 32,547 had actually arrived in the country.

This gap between those who had been approved to enter and those entering the country points to the impact of limited MIQ capacity. In this case, it was overseas workers with border exceptions who were impacted. But New Zealand citizens desperate to return home also came up against the same barriers (as we discuss in section 4.3.5.1). Frustrations were heightened by the perception that some groups, such as sports teams, were ‘taking up’ MIQ spots that could otherwise have been available to New Zealanders desperate to come home.

4.3.5 While there was little operational readiness to deliver quarantine on a large scale, the legislation was sufficiently enabling and the MIQ system was rapidly implemented. But as time went on, problems became apparent

Going into the pandemic, the Health Act 1956 gave the Government the power to use quarantine and isolation. However, the legislation was suited more for quarantining individuals, and officials told us it was challenging to apply it at such a large scale.

The government’s existing quarantine plans assumed an influenza pandemic. The guiding document, the New Zealand Influenza Pandemic Plan 2017, required the Ministry of Health and district health boards to be prepared to use ‘local quarantine facilities’.53 In practice, this meant the district health boards maintaining contracts with local motels and other accommodation providers for potential quarantine purposes; however, we heard that some of these contracts had lapsed before COVID-19 emerged. The possibility of quarantining entire communities and placing travellers in mandatory quarantine on arrival was canvassed in the plan, but such measures were considered unlikely to be effective and therefore not included in pandemic planning.54

Despite the lack of prior planning – and the initial uncertainty as to how long COVID-19 would affect the country – the MIQ system was nonetheless up and running very quickly. Over time, however, the system came under increasing strain, as did the travellers depending on it. Many of the contributing factors have already been thoroughly examined in reviews by government agencies, researchers and independent authorities such as the Ombudsman and the High Court. We have considered their findings and insights alongside other evidence received during our Inquiry, but have not repeated their detailed analyses. The main concerns they raised are outlined in section 4.3.5.1.

4.3.5.1 Managing MIQ capacity and demand

Whether and when most people could enter Aotearoa New Zealand was ultimately determined by MIQ capacity, not by border settings. It is therefore unsurprising that MIQ capacity, and the mechanisms the Government used to manage and prioritise demand, became highly contentious issues. The lingering anger, distress and mistrust they caused were evident in many of the public submissions we received and in our discussions with stakeholder groups (see ‘Spotlight’ in this section).

From the start of the pandemic, the likely demand for MIQ places and the capacity that would therefore be required were hard to predict. It was unknown how many of the thousands of New Zealanders living overseas would want to return, and when, or how many New Zealanders would choose to leave New Zealand with the expectation of returning.

In the event, demand was higher than the system’s capacity, and options to increase the availability of MIQ places were limited. We note that the Ombudsman reviewed the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment’s actions in managing MIQ capacity and accepted that it had limited ability to significantly increase or free up capacity.55 We also heard from officials that, despite the perception that MIQ capacity was largely constrained by hotel availability, in fact the main constraints were the need to rotate MIQ facility staff and the availability of the health workforce.

It was in response to the high demand for MIQ spaces that the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment – from necessity – created the Managed Isolation Allocation System (MIAS) in October 2020. For users, the system required an anxious wait online to secure an MIQ voucher through what many perceived as a lottery. As one user noted, ‘we basically have to spend hours constantly refreshing a screen and as soon as a spot appears and we attempt to click and claim, we are crushed with an “already taken” notice’.56 At the same time, constraints in MIQ capacity meant there had to be a system for allocating places, and that many prospective travellers would miss out.

The system included an offline allocation mechanism intended to prioritise travellers with urgent or compassionate reasons for entering Aotearoa New Zealand. A set of criteria was developed for emergency allocations with the goal of ensuring fairness and consistency across decisions. Officials spoken to by the Inquiry told us that emergency allocation decisions were some of the most difficult and fraught that they had to make during the pandemic.

In a judicial review application to the High Court, Grounded Kiwis challenged aspects of the MIQ system, which they said operated as unjustified limits on citizens’ right to enter New Zealand. The High Court held that while the system did not in and of itself amount to an infringement of New Zealanders’ right to enter their country, the evidence indicated that at least some New Zealanders had experienced unreasonable delays in exercising their right to enter. The judge found that:

“Although MIQ was a critical component of the Government’s elimination strategy that was highly successful in achieving positive health outcomes, the combination of the virtual lobby and the narrow emergency criteria operated in a way that meant New Zealanders’ right to enter their country could be infringed in some instances in a manner that was not demonstrably justified in a free and democratic society.” 57

The Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment accepted the Court’s findings.58 Evidence cited by the Ombudsman in his review of the MIQ allocation and booking system shows that officials and ministers were aware of the system’s potential limitations when developing it in 2020. In particular, they recognised the system lacked the capacity to prioritise travellers with urgent needs, especially given demand exceeded supply. They were also aware of the potential risk of temporary visa-holders being allocated places ahead of New Zealanders, and of long waits for New Zealand citizens and residents wanting to return home.59 However, given the urgency as well as challenges in how to assess ‘need’ in a rapidly changing situation, it was felt other options were not feasible.

In fact, the possible risks which officials identified were exactly what transpired – despite the introduction of the virtual lobby system (which for many people amplified their anxieties and frustrations) and despite the offline allocation system providing an alternative pathway for travellers with the greatest needs. In reality, those seeking an offline allocation voucher – including people dealing with emergencies and hoping for compassionate treatment – had to meet a set of criteria which were ‘interpreted strictly and require[d] an inflexibly prescribed form of evidence’, according to the High Court.60 As the Ombudsman found in his 2022 report on the MIQ allocation system, the offline option simply ‘did not encompass the situations of many people with a genuine need to travel’.61 In public submissions to the Inquiry, we also heard that the system felt depersonalised, that people wanted to speak to someone directly, not fill in an application form. As one submitter said of the MIQ system more generally, all the thousands of overseas New Zealanders wanted was ‘something like a helpline where they can actually … speak to a real person for counselling or advice and help on their situation’.

This and other public submissions lent weight to the Ombudsman’s comments about the shortcomings of the MIQ allocation system as a means of fairly managing capacity and prioritising people with urgent or compassionate reasons for travelling – such as pregnant women, separated families or people visiting relatives who were unwell. Even when the emergency management criteria were at their widest, the Ombudsman noted, ‘[they] were too limited to capture large numbers of people with a genuine need to travel’.62

Spotlight: Stranded Kiwis | Ngā tāngata o Aotearoa kua raru ki wāhi kē

On 18 March 2020, the Minister of Foreign Affairs and Trade Winston Peters urged the estimated 80,000 New Zealanders63 thought to be temporarily overseas to ‘come home now’ if they could: ‘If you’re travelling, it’s very likely you could be shut off very shortly.’64

The next day, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade issued a safe travel notice echoing this message. By now the Ministry was receiving 100 calls a day from anxious New Zealanders, mostly asking for Government assistance with repatriation.65 On that day alone, 6,700 passengers returned to New Zealand.66

By 29 March 2020, some 20,000 New Zealanders had returned.67 Others would remain effectively stranded overseas for weeks or months, unable to get flights or – once the MIQ system was in place – to secure a spot in MIQ. They were a diverse group: students, young professionals working overseas, seafarers and superannuitants. However, many shared a sense of anxiety, frustration or pain at being unable to get home:

“It was massive impact wise. I had been made redundant recently and wanted to travel home to NZ, but with the uncertainty around when this could happen, applying for jobs, or rather knowing which country to apply for jobs, made life difficult.”

We also heard from submitters left distressed and angered by an MIQ system they considered did not prioritise, or allow exemptions for, people stranded overseas in difficult circumstances, including those wanting to come home to say goodbye to dying relatives.

“[T]he fact that quarantine spots were made available to entertainers and other non-Kiwis also made me furious. Many friends were unable to attend key family events, and some even missed their parent’s last moments, or were unable to attend the funeral.”

Among those who managed to get an MIQ spot, there was gratitude for the system that had allowed them to get home – as we heard in the public submissions.

“We were very impressed by how the entire NZ quarantine system had been set up on relatively short notice and with the cooperation of a huge number of varied organisations and personnel.”

Some submitters appreciated that even if Aotearoa’s New Zealand’s border and quarantine controls meant they could not readily come home, they helped the country avoid the devastating impacts experienced elsewhere:

“I would like to stress that the closure of the international border did not bother me, and that I understood that stringent border control was necessary to maintain normal life internally in NZ … [and] prevented a substantial increase in mortality rates over a sustained period of time.”

The voluntary organisation Grounded Kiwis, formed in mid-July 2021, helped people make emergency applications for MIQ spots. The group told us that the evidentiary burden fell entirely on applicants, but the evidence needed to support an application was often simply unavailable. ‘This system didn’t work and wasn’t fit for purpose. People in really dire situations could not get spots,’ Grounded Kiwis said.

“We applied for an emergency room allocation through category 5 under financial hardship but we were denied despite supplying endless proof of our situation and sleeping on a friend’s couch in Brisbane.” 68

Grounded Kiwis also advocated on behalf of people shut out by the ‘virtual lobby’ system, writing to the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment in September 2021: ‘The equity issues of using a lottery style system for what is a fundamental right of citizens, the insufficient MIQ supply to meet demand, and the failure to consider alternatives to MIQ, continue to cause immense concern’.69 Submissions we received echoed this sentiment, describing the so-called lottery as ‘cruel’, ‘unfair’ and ‘criminal’. Messages which Grounded Kiwis received during the pandemic from New Zealanders stranded overseas give insight into the despair felt by people who were separated from home and whānau, often under financial as well as emotional pressure, their lives ‘in limbo’ for an apparently indeterminate time:

“It’s life shattering because my wife is sick in NZ and my two little children are with her. I’m trying to get back to help care for all three of them.”

The distress did not always end when the border reopened and MIQ ended. Some public submitters told us that, two years on, they still felt ‘hopeless’ and ‘disenfranchised’ from the place they once called home.

“The treatment of myself, and other overseas citizens, by the MIQ system, and specifically the emergency application request system … has left me with a profound sense of anger, bitterness, and, at times, a hatred of the country of my birth and the functioning of its government.”

4.3.5.2 Facilities and staffing

The use of hotels as MIQ facilities presented challenges for infection control and wellbeing – particularly the lack of outdoor space for physically-distanced exercise, the absence of appropriate facilities for children, and challenges accommodating people with specific needs.

It also raised challenging workforce issues. The more than 3,700-strong MIQ workforce70 comprised a mix of government employees from multiple entities alongside private sector employees (mostly hotel staff) and subcontractors, all on a variety of employment contracts. Many worked long hours in conditions acknowledged to be demanding; some staff reported being stigmatised at home or in their communities and required ‘strong pastoral care’.71 Alongside these workers, 600 Defence Force staff were deployed at MIQ facilities at any given time. While the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment described their presence as ‘important in terms of supporting public trust and confidence in the MIQ system’,72 there is also evidence of tensions between the military and civilian cultures.73 Some MIQ users clearly found the military (and Police) presence confronting. One woman felt they were ‘treated like criminals. Our exercise yard was a car park where we were observed by security and managed by military, told to walk in a circle and not speak to anyone.’ However, we also heard about MIQ facilities in the Waikato whose operating ethos – mahi tahi, or working together – was borrowed from the Defence Force: public health officials told us of an ‘amazing local relationship with the armed forces managing the facilities – they enjoyed working here’.

The fact that MIQ facilities were not purpose-built for quarantine created a range of problems for staff and users. An assessment commissioned in April 2021 found the hotels were ‘not optimally configured to manage separation of returnee flows on entry, exit and inside the building’, and security and ventilation systems needed remediation.74 Although the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment canvassed the possibility of building dedicated quarantine facilities – or refurbishing existing buildings to the necessary public health standards – the time and cost involved meant these were not seen as realistic solutions to immediate needs.75 Later, officials developed a business case for establishing future MIQ facilities; with options including a mix of Crown-owned bespoke facilities and hotels. But by early 2022, the situation had changed so significantly that this advice was considered no longer relevant, and the MIQ system was wound down.

Despite all the challenges, it is clear that hotels were made to work as quarantine facilities. The evidence shows that the MIQ system learned from its mistakes and the frequent reviews of its operations,xv and made improvements in response. For example, following some well-publicised instances of people spreading COVID-19 into the community after leaving MIQ, procedures were strengthened to ensure thorough cleaning and ventilation, and steps were introduced to minimise the risk of guests becoming infected after their final test (required on day 12 of their 14-day stay).

4.3.5.3 Community cases

From August 2021, as Delta cases were increasing, accommodating community cases in MIQ began to create significant operational and governance challenges for the MIQ system. It was not in fact a new development – providing accommodation for positive cases who could not safely isolate at home had always been one of the functions of MIQ. But the rapid increase in the number of community cases during the Delta outbreak meant that a significant number of MIQ rooms had to be removed from the available inventory for international arrivals to accommodate community cases. By the beginning of November 2021, 360 community cases were in MIQ facilities, along with 25 close contacts in managed quarantine.76

According to the review of MIQ governance, ‘The evolution of MIQ from a border protection response to a mixed border/domestic response has changed the risk profile for MIQ. … [D]omestic cases are placed in MIQ by way of an assessment under a health order and have little time to prepare. The nature of the circumstances that give rise to the health order can further raise risks.’77

Senior MIQ managers interviewed as part of a review of MIQ governance shed more light on those risks. In the past, MIQ had worked well as a border intervention: ‘We knew our swim lane,’ said one interviewee. Now, ‘the most vulnerable and unwell people are being triaged into MIQ by medical officers of health’, placing pressure on a system not designed for people who were presenting with ‘vulnerabilities, health concerns, addictions or violent behaviour’. There was no over-arching all-of-government plan to help the system adapt to its community care role, and gaps in governance were evident, interviewees reported.78

Health officials were also concerned about an increasing emphasis on using MIQ as part of the domestic pandemic response. One told us that apparently little attention had been paid to how increasing community case numbers might impact MIQ capacity. At that time, little work had been done on other options for supporting community cases, such as the Care in the Community programme – despite ‘knowing that we were going to run out of managed isolation beds’. Other health officials and MIQ healthcare workers described accommodating domestic cases as operationally challenging. This was not its primary purpose, and the distinctive needs of this particular category of cases presented clinical, social, legal and equity risks. Those ordered into MIQ often arrived with ‘high and complex clinical and psychosocial needs’ of a kind that the facilities and staff were not prepared for. Many also needed translation services, which were hard to find at short notice.

However, health officials also noted that the profile and needs of the ‘typical’ MIQ user were already changing by the time the number of community cases in MIQ started increasing. At the start of the pandemic, most returnees ‘had been travelling overseas, and therefore generally had low health needs. Over time, a greater proportion of returnees were … returning to Aotearoa New Zealand to get away from challenging pandemic environments overseas, or for challenging family circumstances (e.g. to visit dying relatives, or to attend a funeral). It became more common for these returnees to have higher and more complex health and wellbeing needs – including mental health and addictions needs – than those arriving earlier in the response.’

4.3.5.4 Governance and decision-making

Responsibilities for the MIQ system were split between the Ministry of Health and the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment. This may have been the only practical option at the time the system was established, but it led to frustrations and some operational problems.

The split responsibilities also affected governance and decision-making. A review carried out by the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment in November 2021 found that some governance elements were working effectively. However, ‘the number of different governance entities and lack of a clear point of responsibility for the overall COVID-19 response expose the challenge of coordinating the response and planning at a system level’. That challenge had fallen to the Minister for COVID-19 Response.79 Among specific concerns the review raised:

- The separation of responsibilities between the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment and the Ministry of Health was problematic. ‘[MBIE] is a recipient of health advice, and largely unable to influence decisions already made by the Ministry of Health (MoH). Whilst MIQ has MoH involvement in its operational governance processes it does not have its own clinical expertise’ the reviewers noted.80 The Minister for COVID-19 Response also expressed frustration with the separation of responsibility, writing on a 2021 Ministry of Health briefing about the implications for the health system of more returning travellers passing through MIQ facilities: ‘I’m disappointed that this is not joint advice with MIQ. I would like you to work together to set out a way forward ASAP. This approach is not constructive’.

- The lack of a single point of integration (below ministerial level) for the COVID-19 response made aligning policy and operations more difficult and raised the risk of trade-offs not being fully considered from a system-wide perspective. MIQ leaders interviewed by the reviewers reported ‘no clear visibility of an overall COVID-19 response plan’ and ‘[no] significant level of conversation about future direction’. One example was the heavy commitment of Defence Force personnel to MIQ, a potential risk to the Defence Force’s capacity to respond had another major crisis or threat arisen during this period.81

- While the challenges of getting accurate data from varied sources in a fast-paced environment should be acknowledged, a review carried out in November 2021 found inadequacies in the governance and management of MIQ data.82

xiv Although not purpose-built for quarantine, this refurbished ‘cabin-style style’ facility near Darwin shares many of the features of a purpose-built facility. Originally built as mining accommodation, it consists of many cabins with space between them, allowing good natural ventilation and thereby avoiding the risks of aerosol transmission in spaces like hotel corridors.

xv For example, the ‘Rapid Assessment of MIQ’ commissioned by the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment in April 2021, and the Ombudsman’s report into conditions in six MIQ facilities he inspected in Oct–Dec 2020.