6.2 What happened: economic impact and responses I aha: Ngā pānga me ngā urupare ōhanga

6.2.1 What happened

The COVID-19 pandemic was a global event, and its impacts on Aotearoa New Zealand’s economy cannot be separated from global economic conditions that existed when it started or were created by it. We touch on these influences and draw brief international comparisons throughout this chapter.

Broadly speaking, New Zealand’s economic response to the pandemic, as well as the trajectory of economic developments that unfolded, were in line with what happened elsewhere.1 There were some differences that can be attributed to both the relative generosity, and extended duration, of New Zealand’s economic response.

Central government borrowedi and reprioritised existing spending to fund the key elements of the pandemic response – from scaling-up critical public health functions like contact tracing, to providing wage subsidies for affected workers, delivering housing and social support to help people isolate safely, and offering support for businesses and recovery initiatives. These actions were aimed at supporting strict public health measures including border closures, temporary lockdowns and social distancing, while also cushioning their adverse economic and social impacts.2

The Reserve Bank of New Zealand took early action simultaneously with central banks around the world, to address vulnerabilities in global financial markets. It supported the economic response by purchasing debt on the open market, a move intended to lower interest rates and allow financial markets and the banking system to keep functioning. The Reserve Bank also prioritised ensuring households and businesses had ongoing access to credit, at reasonable rates.

6.2.1.1 Initial uncertainty

Very early in 2020, there were perceptions that COVID-19 might be similar to the 2002-2004 SARS outbreak, which had a relatively small economic impact on Aotearoa New Zealand.3 By late January and early February 2020, however, it became apparent to both the Treasury and the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment that the outbreak of COVID-19 in China had already started creating difficulties for New Zealand export sectors that were particularly exposed to the Chinese market (specifically forestry, rock lobsters and tourism) and that these difficulties would likely only increase.

As more information came to light from around the world, the Treasury worked on scenarios and an initial framework for policy responses. In early March 2020, it provided advice to Ministers on an overall intervention strategy for economic policy.4 The briefing noted that New Zealand was likely to face a long-lasting economic shock and set out potential components of an economic response. They included a targeted wage subsidy scheme, a broader package of options to support economic activity, and a large fiscal stimulus package.

This briefing suggested a set of principles to guide any economic response: that it should be balanced and proportionate, aligned with the broader Government direction, sustainable, easy to implement and adopt a ‘least regrets’ii approach.5 It also advised caution, and referred to potential long-term fiscal sustainability challenges and the need for robust exit strategies.

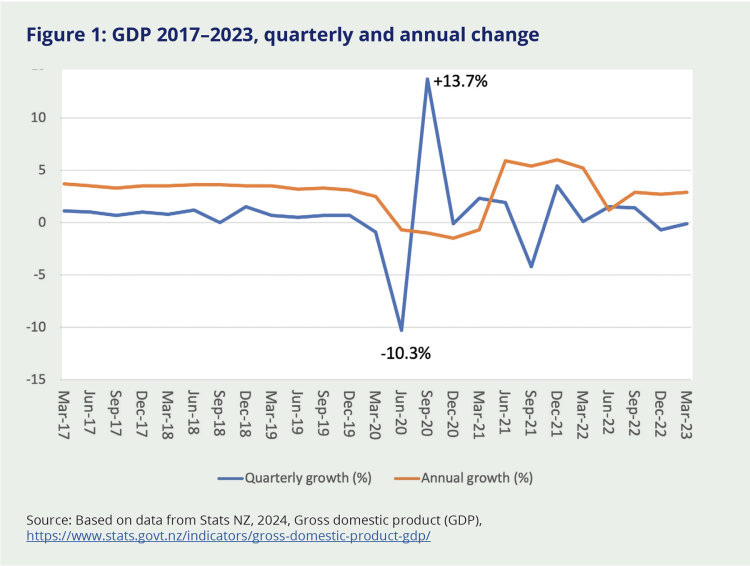

In these early stages, there was deep uncertainty about the potential economic impacts. Subsequent scenario-based estimates which the Treasury developed in April 2020 suggested that GDP might fall by between 13 and 33 percent, and that the unemployment rate might climb to as high as 13 percent, or even up to 26 percent in the most severe scenario.6 These highly pessimistic scenarios did not pan out, no doubt partly because of the policy responses Government introduced. In reality, while GDP fell sharply in the first quarter of 2020, as an annual measure it fell by only 2 percent.7 Unemployment peaked at 5.2 percent in mid-2020, from a pre-pandemic level of 4.1 percent.8 No doubt, these better-than-scenario outcomes reflected, at least in part, the speed and generosity of the Government response.

Figure 1: GDP 2017–2023, quarterly and annual change

Source: Based on data from Stats NZ, 2024, Gross domestic product (GDP), https://www.stats.govt.nz/indicators/gross-domestic-product-gdp/

6.2.1.2 The trajectory of the Government’s economic and fiscal policy response

The main economic policy agencies (led by the Treasury and the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment) advised an all-of-government approach to developing and managing the Government’s fiscal and broader economic policy response to the pandemic. The response was developed with Ministers and agreed by Cabinet.

The Government initially used a ‘3 waves’ model to structure its economic response. The model was based on a standard adverse events recovery framework used by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). It was explained to the public by then-Finance Minister Grant Robertson on 24 February 2020.9 A few days later, he described the successive phases of the economic response – fighting the virus and cushioning the blow (wave 1); positioning for recovery and kickstarting the economy (wave 2); and resetting and rebuilding the economy (wave 3).10

As the pandemic continued, and the country moved up and down the Alert Level Framework, the ‘3 waves’ terminology became less useful and eventually fell out of use. The three budgets that followed (2020, 2021, 2022) included initiatives for all three waves. There was some inevitable blurring and overlapping between the waves because the pandemic continued for much longer than initially expected, and changes in alert levels due to community outbreaks made it necessary to return to, or extend, earlier support measures. The discussion of the Government’s economic and fiscal policy response that follows is therefore organised around Budgets 2020, 2021 and 2022 rather than the waves as initially defined.

The Government initially used a ‘3 waves’ model to structure its economic response.

Response: March 2020 Economic Response Package and Budget 2020

On 12 March 2020, the Government announced an immediate ‘business continuity package’ in response to COVID-19. It included a targeted wage subsidy scheme for workers in the most affected sectors.11 On 17 March, this proposal was expanded into a $12.1 billion COVID-19 Economic Response Package including $5.1 billion in wage subsidies, a $500 million boost in health funding, and $2.8 billion in social supports.12 A range of business tax measures were also introduced, along with a package of support for the heavily impacted aviation sector.

In May 2020, the COVID-19 Response and Recovery Fund (a notional fund outside the budget process) was announced. In total, $70.4 billion was allocated to COVID-19 response and recovery initiatives, including the initial response package of $12.1 billion (announced 17 March 2020) and $58.4 billion allocated from the COVID-19 Response and Recovery Fund before its closure in Budget 2022. The amount allocated for each initiative was the expected fiscal impact across the forecast period at the time the decision was taken. The Treasury advised Government to focus the support package as much as possible on broad-based, economy-wide measures like wage subsidies and tax relief measures. This advice reflected considerations of efficiency, a wish to avoid targeting support at specific sectors and industries, and the expectation that the shock itself would have widespread effects. While these considerations were reflected in the package, Budget 2020 also funded some more targeted measures. These included specific support for affected sectors (like aviation, tourism and the cultural sector) and direct financial support for specific companies, like that available through the Strategic Tourism Assets Protection Programme.13 The package also included a range of support measures for education and the social sector at large.14

The overall COVID-19 Response and Recovery Fund package represented the second highest additional spending and/or revenue foregone in relative terms by any OECD government in response to COVID-19 (although it should be noted that some countries resorted, substantially in a number of cases, to a variety of less direct supports, including guarantees, loans and equity, that New Zealand used only sparingly).15 Treasury officials advised the Government that the benefits of this spending would outweigh the possible costs of debt rising above 50 percent of GDP. Treasury considered that the economic supports were proportionate to the health response, given the stringency of the public health measures taken at times during the pandemic.

Some of the people who made public submissions to our Inquiry expressed appreciation for the generosity of this economic response:

“I was grateful for the economic support from the government so that I could stay in business, keep paying my workers, and continue contributing to the economy.”

“When the government announced a financial support package for people to stay at home, I felt enormous relief as this would be what was needed to allow people to survive financially when they couldn’t work.”

Spotlight: The COVID-19 Wage Subsidy Scheme | Te Kaupapa Utu Moni Āwhina KOWHEORI-19

The largest single item of expenditure during the response – $18 billion in total – was the COVID-19 Wage Subsidy Scheme, including its extensions and variations. It supported workers indirectly by enabling businesses (including people who were self-employed) to continue to pay and employ their staff.16

The scheme had two core objectives: to maintain employment and keep workers connected to their jobs, and to support workers’ incomes during temporary disruption caused by COVID-19. It was available to businesses that had lost at least 30-40 percent of their revenue (the percentage varied during the course of the scheme) due to COVID-19 during specified periods (five in total, usually coinciding with national or regional lockdowns). The eligibility criteria for the scheme were tightened over time.17

At its peak, the Wage Subsidy Scheme covered 72 percent of employing firms and supported 59 percent of total employment.18 Two independent evaluations found that payments generally flowed through to workers from their employers as intended.19 One found that firms appear to have largely complied with their obligations to pass on the subsidy payments to their workers and to pay them at least 80 percent of their previous earnings when possible.20

Many public submitters to our Inquiry commented on the scheme. Their comments reflected gratitude for the stability it provided, complaints about its adequacy, questions about its fairness, and concerns about its long-term economic implications.

“My company took advantage of the wage subsidy – it was good to be pretty confident we’d keep our jobs.”

“We could pay our staff and not worry about the expense, which would have put our business close to going under […] It relieved stress in a very fraught time. I was incredibly impressed about how quickly it was rolled out, and how fast the payment was.”

“The subsidy payment […] was well less than 50 percent of my normal income which left me short for paying my normal outgoings and hence getting behind in payments and therefore into debt.”

“Employers that did not need the subsidy should have been made to pay it back, i.e. those that made significant profits.”

“Be aware that economic decisions made will have impacts into the future (like inflation) which we are now suffering from, while the wage subsidy was necessary at the time, it went on for too long.”

The Wage Subsidy Scheme was developed jointly by the Treasury, the Ministry of Social Development, the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment, and Inland Revenue early in the pandemic. It was largely based on a previous scheme that the Ministry of Social Development had implemented during earlier crises, including the Canterbury and Kaikōura earthquakes.

Initially it was designed to focus on the sectors most affected; at that stage these were forestry and tourism. As the full implications of the pandemic became clear during March 2020, it was rapidly repositioned as a broad-based scheme and was launched nationally for all sectors on 17 March 2020.21

The Ministry of Social Development was the main delivery agency, in part because operational barriers ruled out Inland Revenue. Due to legislative barriers, ACC (which had the required functionality in their system and offered to help) could not deliver it either.iii

Implementing such a wide-reaching wage subsidy in a short period of time in March 2020, under extremely testing circumstances, was a great achievement – a workforce had to be trained, while at the same time much of the work and income functions of the Ministry of Social Development had to pivot to online-only delivery. The Ministry used the payment mechanism established for the Kaikōura earthquake response, which limited the ability to apply a greater level of calibration and targeting. It needed to be implemented quickly and by necessity (in the absence of a fully designed system pre-pandemic and the unavailability of the Inland Revenue system), relied on a high-trust model. This inherently came with a risk of fraud.

When the Office of the Auditor-General reviewed the Wage Subsidy Scheme in 2021, it reported that ‘many of the steps public organisations took to protect the Scheme’s integrity were consistent with good practice guidance for emergency situations’,22 but recommended that ‘when public organisations are developing and implementing crisis-support initiatives that approve payments based on “high-trust” they ... put in place robust post-payment verification measures’.23 The Auditor-General also recommended that the Ministry of Social Development carry out further enforcement work’.24 Later, a Martin-Jenkins evaluation of the Wage Subsidy Scheme noted that the relationship between the policy and operational risks (including integrity) had not been sufficiently explored when the scheme was being developed. Throughout the scheme’s successive phases, Martin-Jenkins said agencies had worked to identify and mitigate risks to improve its operation.25

During our Inquiry, public criticisms were made of the Ministry of Social Development’s approach to compliance through a High Court judicial review, which was dismissed, and an Advertising Standards Authority complaint, which was partially upheld.26 We are aware of criticisms by the peer reviewer of the methodology used in the Martin-Jenkins evaluation.27

Some ineligible businesses were paid the subsidy. As of 27 September 2024, companies had made over 25,000 repayments, totalling $827 million. In addition, 30 people had been convicted of fraud and sentenced, while a further 48 were still before the courts.28 At the time of writing this report, prosecutions were still ongoing. Civil recovery action was underway against fifty businesses.29

It was not always straightforward for employers to implement the wage subsidy. For example, businesses had to try their hardest to pay employees at least 80 percent of their usual wages while receiving the subsidy for them. If that wasn’t possible, they had to pay employees at least the subsidy payment rate. Some businesses apparently believed this relieved them of the responsibility of paying more than 80 percent of the wage, even if they could, and the interaction with employment law was complicated. The Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment managed this aspect of the Wage Subsidy Scheme and provided phone and online support about the scheme. We were told that the situation was sometimes unclear to employers and employees alike, and we consider greater clarity and guidance could have been provided.

Despite these challenges, the subsidy supported millions of workers, including by protecting employment and thousands of businesses at a critical time. We will return to its effectiveness and impacts in the next section.

Recovery: Budget 2021

A year on from Budget 2020, Aotearoa New Zealand was enjoying the fruits of the early success of the elimination strategy. While the international border remained ‘closed’, there was no community transmission of COVID-19, the entire country was at Alert Level 1, and most people could go about their daily lives relatively unencumbered. The pandemic appeared to be over (in Aotearoa New Zealand at least), vaccinations were on their way, and the Government had reason to believe that the main task for the economy was now recovery.30

The May Budget 2021 reflected this focus. It retained the Response and Recovery Fund, but with refreshed policy goals: to continue to keep New Zealanders safe from COVID-19, accelerate the recovery and rebuild, and lay foundations for the future. Key investments included $4.6 billion from the COVID-19 Response and Recovery Fund, mainly focused on accelerating housing construction; $1.5 billion for the COVID-19 vaccine rollout, which was then getting underway; and a $300 million ‘green investment fund’. All investments were aimed at supporting the recovery and rebuild from COVID-19.

In the second half of 2021, during the Delta outbreak and the Auckland lockdown, the Government added a further $7 billion to the Response and Recovery Fund, although not all of it was allocated. This extra funding was targeted at further economic support (including for the wage subsidy in the extended Auckland lockdown) as well as building resilience in the health system, supporting the vaccination rollout, and border and managed isolation and quarantine (MIQ) provision. These, and similar initiatives such as Jobs for Nature,iv were intended to use the opportunities created by COVID-19 to ‘build back better’. We return to this theme with reference to Budget 2022.

Key investments included $4.6 billion from the COVID-19 Response and Recovery Fund, mainly focused on accelerating housing construction.

In total, more than $70 billion of direct funding and tax relief was allocated to the COVID-19 response in Budgets 2020 and 2021, or about 22 percent of 2019 GDP. Not all of it was spent.31 The largest areas of COVID-19-specific appropriation (as calculated on 31 May 2023) were:

- $18.3 billion on business support subsidies (including variants of the Wage Subsidy Scheme between March 2020 and December 2021).

- $4.2 billion for the national response to COVID-19 across the health sector.

- $2.9 billion for the COVID-19 Resurgence Support Payment (a grant scheme that provided firms with non-repayable support to assist transitions between alert levels).

- $2.5 billion for implementing the COVID-19 vaccine strategy.

- $2.4 billion for the Small Business Cashflow Scheme (advanced as loans to small businesses with a 5-year repayment period).v It is too early to know how much of this will be repaid.

- $1.6 billion on isolation and quarantine management.

- $1.6 billion on COVID-19 Support Payments (payments to ongoing and viable businesses or organisations that experienced a 40 percent or more drop in revenue due to public health restrictions, impacts of supply chain disruptions, and lower recreation-related movements – for example, central city businesses that were affected by people working from home).

In addition to these initiatives, the Response and Recovery Fund funded a large number of other support measures, both general and sectoral. These included the COVID-19 Short-Term Absence Payment and the COVID-19 Leave Support Scheme (which provided workers with support to encourage them to self-isolate when they had COVID-19 or were waiting for a test); sectoral support for those areas most affected by the pandemic (including tourism and international education); Jobs for Nature (see footnote iv); and the arts, culture, recreation and sport sectors.

Rebuild: Budget 2022

From mid- to late-2021, some of the medium- to long-term impacts of the economic response to COVID-19 (as well as wider global factors) had started to become apparent, particularly in the form of higher interest rates, increasing costs of living, and continued upward pressure on house prices.

This was reflected in some of the priority spending areas in Budget 2022. By this time, the Response and Recovery Fund had been wound up and the Government’s focus had shifted to ‘building back better’. This involved investing in infrastructure to make Aotearoa New Zealand less vulnerable to future shocks, cushioning the impact of inflation, improving physical and mental wellbeing, and reducing fuel taxes and road user charges to offset rising energy costs.

6.2.1.3 The monetary and financial policy response

‘Monetary policy’ refers to the actions the Reserve Bank of New Zealand takes to achieve and maintain price stability (and, at the time of COVID-19, to support maximum sustainable employment). For the purposes of this report, ‘financial policy’ refers to the measures taken by the Reserve Bank to protect and promote the stability of the financial system. The Reserve Bank has operational independence from the government in choosing which policy instruments it will use to pursue these monetary and financial policy objectives.

During the pandemic, the Reserve Bank maintained low short-term wholesale interest rates, put further downward pressure on other interest rates by purchasing government bonds and funding lending for banks, and relaxed lending restrictions on the loan to value ratio.32 All these measures were intended to soften the impact of the downturn, giving businesses and households access to affordable borrowing if needed. In addition, the Reserve Bank used various means to ensure that the financial markets at large, and the banking system specifically, continued to operate efficiently and safely.

According to the OECD, central banks around the world – including New Zealand’s – acted simultaneously in responding to COVID-19 ‘with scale and speed to stabilize financial markets and cushion the contraction in real activity’.33

‘Monetary policy’ refers to the actions the Reserve Bank of New Zealand takes to achieve and maintain price stability.

Monetary and fiscal policy coordinationvi

The Reserve Bank of New Zealand and the Treasury are in regular communication, and exchange information through a range of channels to inform their respective monetary and fiscal policy decisions. However, they do so without compromising the operational independence of the Reserve Bank or undermining the sensitivity of the information Treasury provides to politicians to inform fiscal policy decisions. Examples of this ongoing contact include working-level meetings, regular meetings between the Reserve Bank Governor and the Secretary to the Treasury, collaboration on briefings to the Prime Minister and Minister of Finance in advance of the Reserve Bank’s Monetary Policy Statements, and pre-Budget Treasury briefings to the Reserve Bank. In addition, a Treasury observer participates in the deliberations of the Monetary Policy Committeevii about forecasts and risks in the economy, but does not have a say in decisions. The Reserve Bank and the Treasury have a Memorandum of Understanding (which was in place before COVID-19) formalising much of this working relationship.34

During the COVID-19 period, information-sharing and engagements between the two institutions continued. For example, the Treasury representative on the Monetary Policy Committee regularly advised the Reserve Bank about the high-level figures for the Budget (but without providing actual details) to inform its monetary policy decisions. The information the Reserve Bank was given access to was likely to have included the main macroeconomic drivers of the Budget (such as levels of fiscal stimulus (impulse), percentage changes in tax forecasts, estimates of fiscal increase/reduction (as a percent to GDP). This exchange of information would have assisted the Monetary Policy Committee to think about the balance of risks when making monetary policy decisions before the publication of Budget information.

Nevertheless, there was no active coordination of monetary and fiscal policy in the economic response to the pandemic, in the sense of having a broad common understanding of how they might interact with each other. Such an understanding can matter enormously in a crisis, where matters are evolving fast. If (for example) both Reserve Bank monetary policy and Treasury fiscal policy are strongly stimulating the economy, they may create too much stimulus. Or, if monetary and fiscal policy diverge, they may unintentionally work against each other. However, we saw no evidence of the Reserve Bank and the Treasury jointly advising the Government in a coordinated manner on the broad pattern of how the quantum and mix of fiscal and monetary stimulus should be provided, and how these should be adjusted as the pandemic evolved.35

6.2.1.4 Pressures on supply chains

While Aotearoa New Zealand’s geographical remoteness worked in our favour – simply put, our distance from other countries helped keep the virus out – we were exposed to weaknesses in international supply chainsviii that developed during the pandemic. These weaknesses influenced the way that domestic supply chains operated.

There were several contributing international influences. The availability of raw materials as inputs for manufacturing became more constrained,36 and some countries ‘reshoring’ production to promote self-sufficiency and unwind trade integration37 disrupted trade and supply chains. International shipping delays and supply shortages – along with the impact of other countries’ public health restrictions on supply chains, and port congestion in other countries38 – all created problems and uncertainty for New Zealand. These included delays to incoming shipping services, ships ‘bunching’ at New Zealand ports, problems with container availability and positioning and over time, substantially higher international shipping freight rates. This led to uncertainty and higher costs for importers and exporters, and their customers. Meanwhile border closures led to large-scale reductions in aviation services and air cargo capacity to and from New Zealand, and higher air cargo freight rates.

These problems were international in origin, but they were compounded by a range of domestic factors. These included the failed automation project at the Port of Auckland,39 a short-lived requirement that only essential cargo be handled at ports (which led to congestion problems at ports), and the way that businesses had to organise themselves (for example, through completely separate shift crews) to manage infection risks.

Some stakeholders also described a general lack of understanding of key supply chain issues before the pandemic, especially within the public sector. This extended to a lack of understanding about the inputs required by manufacturers of essential goods. As an example, the Ministry of Health initially determined that forestry operations and wood processing at the Kinleith Mill were not essential industries; in fact, the mill is the only New Zealand supplier of chlorineix for drinking water.

The Government took action to protect supply chains

In response to supply chain issues, the Government established a Supply Chain Group and accompanying Ministerial Group in 2022. Also significant was its decision right at the start of the pandemic to ensure the aviation system continued functioning, albeit at a reduced level. Submitters praised the rapid response of the Ministry of Transport in this area.

The Government made payments through the Ministry of Transport to a number of airlines (including Air New Zealand) to maintain air cargo capacity, and to ensure as much as possible that airlines retained a presence in the New Zealand market. That was considered essential for the anticipated ‘bounce-back’ once the border reopened. The Government ensured through loans and additional funding that Air New Zealand and the Airways Corporation were kept afloat and operating, and that border agencies had sufficient funding streams to keep operating despite the decline in air passengers. Separately, New Zealand Trade and Enterprise underwrote air cargo capacity on Air Zealand flights for exporters.

The Government did not play as direct a role in keeping maritime supply chains open. Chartering or requisitioning ships was briefly discussed as a ‘worst-case scenario’40 but not progressed. The Government did, however, carry out a number of actions that helped facilitate continued trade. The Maritime Border Order of June 2020 – which formalised the Government’s approach to maintaining export and import trade while managing infection risk from ships’ crew – allowed international crew changes while ships were in Aotearoa New Zealand. Many other countries did not allow crew changes, which led to welfare issues. Being able to exchange crew in New Zealand gave shipping companies one more reason to continue to serve the country.

In general, the provision and efficiency of shipping and related services to Aotearoa New Zealand throughout the pandemic remained in the hands of the sector – with shipping companies, importers and exporters, freight forwarders, logistics companies and port companies.

Being able to exchange crew in New Zealand gave shipping companies one more reason to continue to serve the country.

In some parts of the supply chain, pre-existing relationships between government decision-makers and supply chain operators were limited or entirely absent. Examples included food exports and the local packaging supply sector, food manufacturing and the waste recovery and recycling sector, shipping and building supplies. While these relationships took a while to establish, they became indispensable; stakeholders told us that building them was a positive outcome from the pandemic.

Government agencies and sectors liaised closely to manage supply chain problems as they arose – whether this meant the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade or New Zealand Trade and Enterprise working internationally; or officials, cargo interests and interisland shipping providers working through the availability of space on the Cook Strait ferries. Officials also worked closely with the major supermarket chains. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade regularly collected and disseminated information to businesses about international trade and supply chain trends. New Zealand Trade and Enterprise set up a supply chain advisory service and increased its ability and capacity to help exporters in the market who were unable to travel. We heard that the ability of the Ministry of Transport to work between the international transport sector and the Ministry of Health was important.

Government agencies and sectors liaised closely to manage supply chain problems as they arose.

i By issuing government debt.

ii A ‘least regrets’ approach to decision-making is one that aims to minimise the risk of the worst possible outcomes.

iii Inland Revenue was in the middle of upgrading to a new IT system and, under their legislation, Inland Revenue and ACC were not authorised to perform this function. The Ministry of Social Development’s system did not have the functionality to achieve more granular targeting/tailoring of the response – it was a blunt tool. Needing to pass legislation would have slowed down getting Wage Subsidy Scheme payments ‘out the door’.

iv Part of the COVID-19 recovery package, Jobs for Nature was a $1.19 billion programme that managed funding across multiple government agencies to benefit the environment, people and the regions. It was intended to help revitalise communities through nature-based employment and to stimulate the economy post COVID-19.

v With two years interest free and a below-market interest rate of 3 percent per annum after that.

vi See https://www.treasury.govt.nz/sites/default/files/2024-08/an24-07.pdf for a recent and thoughtful discussion on monetary and fiscal policy coordination.

vii The Monetary Policy Committee was established by the Reserve Bank of New Zealand (Monetary Policy) Amendment Act 2018. The new Act replaced the Governor as sole decision-maker with a Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) as the decision-making body. The Remit (under the Act), issued by the Minister of Finance, sets the inflation target and the MPC has operational independence on how the target will be achieved. The MPC has four internal and three external members. The Minister of Finance appoints both internal and external members based on recommendations from the Board of the Reserve Bank.

viii In simple terms, a supply chain is a sequence of processes involved in the production and distribution of a commodity. Supply chains include – but are also broader than – transport and logistics systems. They describe any chain of processes, businesses and movements by which a product is produced and distributed.

ix Chlorine is a byproduct from the mill’s manufacturing process.