8.5 Our assessment: Vaccination requirements Ngā whakaritenga rongoā āraimate

We start our assessment of vaccination requirements with an overview of the basis on which the Government introduced them, including the central trade-off between protecting and looking after the public (by advancing the goals of the pandemic response) and infringing people’s right to refuse medical treatment.

We set out the Inquiry’s assessment of whether the Government got this balance right overall and in some specific instances in section 8.5.1. We try to make these assessments based on knowledge that was available at the time.

In section 8.5.2 we extend our assessment to consider the impact of vaccine mandates – including evidence on their effectiveness in increasing vaccine coverage and public health protection, challenges in their implementation, and the wider social and economic impacts of requiring people to be vaccinated. The Inquiry acknowledges that the discussion in section 8.5.2 draws on material and evidence that was not always available to decision-makers at the time. The purpose of this discussion is to draw out lessons to help inform future pandemic responses where use of vaccine mandates may be considered.

The purpose of this discussion is to draw out lessons to help inform future pandemic responses where use of vaccine mandates may be considered.

8.5.1 Assessment of the case for vaccination requirements

Requiring people to be vaccinated in order to work or be present in particular settings is a significant decision. The Government recognised that such a requirement represented a limitation on people’s right to refuse medical treatment, and that any benefits needed to be carefully weighed against this infringement. It was also advised about the wider risks of requiring vaccination and the potential for discrimination, erosion of trust and social cohesion, and disproportionate impacts on Māori.

There are two benefits of vaccination invoked to justify vaccine requirements. First, vaccination reduces transmission of COVID-19 from one person to another. This means that:

i) for a highly effective vaccine, one may achieve herd immunity – meaning only sporadic outbreaks occur among unvaccinated pockets of the population. Herd immunity was most unlikely for Delta (due to incomplete and waning protection against infection), and impossible for Omicron;

ii) partial or moderate vaccine protection against transmission, and moderate to high vaccine coverage, will dampen transmission, and reduce the peak of waves (in a mitigation strategy) and make it easier to contain any outbreaks (in a suppression strategy); and

iii) other people, particularly those with co-morbidities and who were medically vulnerable, would be protected from becoming infected with COVID-19.

Second, vaccination protects the vaccinated person from illness (even if it does not reduce the risk of them passing the virus on to others). This is a weaker ground for vaccine requirements than the above transmission rationale, as one is now compelling people to be vaccinated for their own benefit against their own judgement, not for the benefit of others. However, in the peak of a serious wave of infection, a requirement of people in public and essential services to be vaccinated may reduce the number off sick at any one time, with a ‘spill over’ benefit to others. Indeed, from November 2021, legislative changes broadened the legal grounds on which vaccination could be required to include such ‘public interest’ goals such as to assist continuity of essential services.

Requiring people to be vaccinated in order to work or be present in particular settings is a significant decision.

Embedded in this reasoning is the assumption that making vaccination mandatory (or requiring it for people to work or be present in particular settings) will result in a meaningful increase in the number of people being vaccinated, over and above what would be achieved via voluntary vaccination. To put it another way, the benefit of requiring people to be vaccinated depends on people taking up vaccination who otherwise would not have done so. Turning to our assessment, given the importance of keeping COVID-19 out of the country, there was a strong case in 2021 for requiring border workers to be vaccinated (in the same way that they were the first group to be prioritised in the vaccine rollout). With the Delta outbreak proving hard to contain, there was also a good case for mandating vaccination for those working with vulnerable people or in high-risk settings – including health, aged care and disability settings and prisons.

It was also reasonable for the government to introduce a simplified health and safety risk assessment tool in late 2021 that employers could use if they were intending to introduce workplace specific vaccination requirements as the country moved away from use of lockdowns and sought to find a way of ‘living with’ established COVID-19 transmission.

Similarly, we consider it was sensible to introduce a vaccine pass system in December 2021 with the intention of reducing the risk of Delta ‘superspreader’ events and protecting vulnerable groups, while reducing reliance on more stringent public health and social measures. These decisions were made in a difficult context where people were having to shift their understandings of risk and adjust to a very different approach to that of the elimination strategy.

The case for requiring vaccination became less clear in 2022 with Omicron. The public health benefit of most vaccine mandates depended on vaccination meaningfully reducing transmission of COVID-19 from one person to another. By late 2021, it was clear that protection against transmission waned in the weeks and months following vaccination. By early 2022, there was evidence that vaccination offered significantly lower protection against transmission of Omicron (now the dominant COVID-19 variant in Aotearoa New Zealand) and that this more modest protection also waned in the weeks following vaccination.

The addition of a booster dose to occupational vaccine requirements arguably meant there was still some potential benefit from requiring people to be vaccinated in order to work in certain settings. But this benefit was smaller than previously since vaccination offered lower protection from transmission with the Omicron variant, although boosting certainly helped. Vaccination rates were also now very high in relevant occupations. The added benefit of vaccination being mandatory in these groups was therefore smaller, given there was little scope for additional people taking up the vaccine who had not already done so.

In section 8.4.5, we established that health officials would have been aware of emerging evidence that vaccination offered very low protection against transmission of the Omicron variant.163 While this evidence weakened the case for vaccine requirements, officials are likely to have been cautious in recommending the removal of vaccine requirements that might offer even modest additional protection. This is illustrated in a High Court ruling from February 2022 concerning occupational mandates.164 An expert witness expressed the opinion that vaccination did not prevent transmission of the Omicron variant. In contrast, the Chief Science Advisor for Health, Dr Ian Town, was more circumspect in his assessment of the evidence, noting that – in relation to Omicron – vaccination was thought to provide ‘some protection against symptomatic disease’, albeit at lower levels than for previous variants.165 Dr Town noted that officials were cautious about placing too much emphasis on early studies, but were continuing to monitor the evolving evidence in this area:

“The information in respect of Omicron is still in its infancy and is evolving. Many of the studies are either in pre-print (have not yet been subject of peer review) or have significant limitations. The Ministry of Health constantly reviews and makes publicly available on its website the most up to date and relevant scientific information.”166

Based on the evidence provided in this case, Justice Cooke concluded (on 25 February 2022) that ‘vaccination may still have some effects in limiting infection and transmission, but at a significantly lower levels [sic] than was the case with the earlier variants’.167

The March 2022 Cabinet paper we discussed in section 8.4.5 stated that the Pfizer Comirnaty vaccine provided ‘an epidemiologically important reduction in transmission’ of Omicron.168 Referencing advice from the Ministry of Health and the Strategic COVID-19 Public Health Advisory Group, the paper took a mixed view on continuing vaccine requirements, recommending the retirement of some (the vaccine pass system, workplace vaccine requirements for staff in associated venues, and occupational mandates for teachers and educators) and the retention of others (occupational mandates for border workers, health workers and prison staff).

As noted previously, by March 2022, the Strategic COVID-19 Public Health Advisory Group assessed the case for vaccine mandates as ‘more finely balanced’ due to a combination of high vaccination coverage and ‘the apparent lowering of vaccine effectiveness against transmission of the Omicron variant’.169 The Group advised the Government to remove vaccine mandates for workers in Fire and Emergency services, the Police, the Defence Force and educational settings, but to retain those for workers in border, healthcare and prison settings. It seems that advisors felt that even a small potential gain in protection from vaccination warranted the retention of mandates in these settings.

A precautionary approach to removing mandates is understandable in the context of growing rates of infection from Omicron after previously stringent public health and social measures were removed. Nevertheless, the case for retaining vaccine mandates became less clear once the peak of Omicron infection had passed (in March 2022), when it was apparent that measures under the COVID-19 Protection Framework were sufficient to manage infection peaks and prevent the health system from being overwhelmed. While many occupational mandates were rolled back in April 2022, mandates for prison staff and border workers were retained until July 2022, and those for workers in high-risk settings (healthcare and prisons) remained in place until September 2022.

The decision to require vaccination involved a careful weighing up of people’s right to refuse medical treatment against the benefits decision-makers believed would result from making vaccination mandatory. This is a judgement call. Decision-makers may reach different views on the most appropriate balance at different times and in different contexts, particularly as evidence of both the costs and benefits of mandates becomes clearer.

It is the view of this Inquiry that the retention of many occupational vaccine mandates until well into 2022 was too long. Once the peak of Omicron had passed, in March 2022, the Government could have confidence that the new COVID-19 Protection Framework was effective in preventing the health system from being overwhelmed and protecting vulnerable groups as far as was possible. It was also becoming clear that vaccination offered limited protection against transmission of Omicron, and that – rather than seeking to control COVID-19 outbreaks – the approach going forward would rely on other measures (including the development of stronger or ‘hybrid’ immunity from people getting infected on top of already being vaccinated) to reduce the severity of infection.

The Inquiry is also of the view that the extension of vaccination requirements into a broad range of workplaces went too far – although we also acknowledge that these requirements were introduced by employers and businesses (under regulatory guidance) rather than the Government, and that many of these employers were responding to expectations on the part of their staff.

It is the view of this Inquiry that the retention of many occupational vaccine mandates until well into 2022 was too long.

On vaccine passes, our Inquiry’s assessment is that there was a case for using passes in the context of Delta infection (in late 2021) as they would have helped lessen superspreader events and outbreak frequency and severity. In practice, however, Omicron was the dominant COVID-19 variant when Aotearoa New Zealand ‘opened up’ in early 2022. Epidemiologically, vaccine passes in the face of Omicron provided only marginal benefit in terms of reducing the spread of infection – although they may have helped somewhat to reduce the peak of the first wave of Omicron infection.xi Those making decisions in January and February 2022 would have had considerable uncertainty about how big the first wave of Omicron infection was going to be and whether it would put pressure on health services. It is understandable that vaccine passes were left in place for the first Omicron wave, albeit it was a decision that could reasonably have gone either way. Notably, vaccine passes were removed promptly after the peak of the first Omicron wave.

The move from encouraging to compelling vaccination was a significant one that affected how many people felt about the pandemic response overall. While vaccination requirements offered a level of reassurance to many in the short term, the long-term impacts of these decisions had negative social and economic impacts (discussed further in section 8.5.2) which – for many people – have been deep and lasting.

The Inquiry notes that vaccine requirements were used in many other countries as part of their COVID-19 responses.170 Decision-makers in these countries would also have considered the trade-off between the increased protection gained from vaccine mandates and the associated constraints on personal freedom. Many of them judged the cost to be ‘worth it’, although some did not. This was a difficult judgement to make. As one summary of international experience notes:

“It is hard to accurately quantify the consequences [of vaccine mandates] such as [loss of] social exclusion, loss of public trust, or inequitable outcomes. Numerous other factors are at play, such as the way a government handled the pandemic overall, wider political campaigns against vaccination or mandates, or frustrations with the way that a mandate was implemented. Another crucial aspect of whether mandates are successful is the political skill and messaging used to introduce them.”171

Many of these factors are discussed further in following sections.

8.5.2 Assessment of vaccination requirements – impacts and implementation

8.5.2.1 Effectiveness of vaccination requirements in protecting public health

Having reflected on the justification for vaccination requirements (in terms of whether the Government had sufficient grounds for limiting people’s right to refuse medical treatment), we now turn to the impacts of these requirements – including their effectiveness in supporting the COVID-19 response, issues with their implementation, and their broader social and economic impacts.

Vaccination requirements had limited impact on vaccination coverage

Aotearoa New Zealand was one of at least 75 countries to use vaccine mandates as part of its COVID-19 response.172 How far these were applied, and to which workforces, varied widely around the world. For example, while in New Zealand it was seen as important to mandate vaccination for the health workforce to protect both workers and patients, in the United Kingdom, frontline health workers were not required to be vaccinated, due to concerns that this would deplete the workforce to critical levels.173

International evidence suggests COVID-19 vaccine mandates had a small positive impact on population-wide vaccination coverage, although this varied widely from country to country and depended on a many factors such as the level of voluntary vaccine coverage achieved without mandates.174 In Canada, where population-wide vaccination mandates were introduced when voluntary coverage was already over 80 percent, they are estimated to have boosted first-dose coverage by 2.9 percentage points, which the researchers call a ‘sizeable increase […] considering the relatively short period in which it was achieved’.175

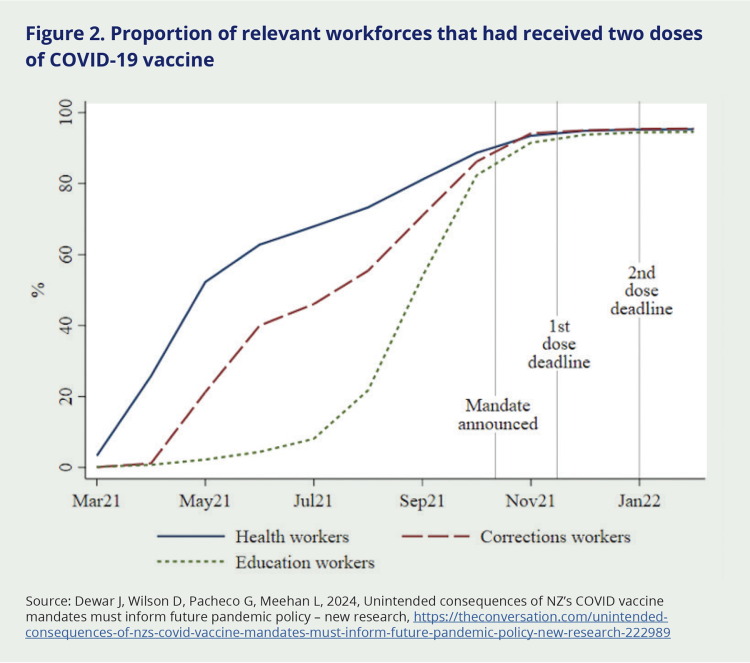

A 2024 evaluation concluded that Aotearoa New Zealand’s occupational vaccination mandates are likely to have had limited impact on population protection from COVID-19.176 The authors noted that vaccination levels in relevant workforces were already very high at the point the mandates were introduced. While vaccination levels continued to rise, the relevant increase appeared as ‘a continuation of an [existing] upward trend rather than a jump in uptake’ as shown on Figure 2.177

Figure 2. Proportion of relevant workforces that had received two doses of COVID-19 vaccine

Source: Dewar J, Wilson D, Pacheco G, Meehan L, 2024, Unintended consequences of NZ’s COVID vaccine mandates must inform future pandemic policy – new research, https://theconversation.com/unintended-consequences-of-nzs-covid-vaccine-mandates-must-inform-future-pandemic-policy-new-research-222989

The report concluded that – since the vaccination mandates had little discernible impact on vaccine coverage – they would not have meaningfully increased population protection from COVID-19:xii

“Overall, the results suggest that in the context of already-high vaccination rates, workforce vaccine mandates may not have provided much benefit in terms of increasing vaccination rates among mandated workers.”178

Specific to the health workforce, the review further found that Aotearoa New Zealand’s vaccination mandates negatively impacted healthcare workers’ employment, and that this may have had wider consequences by exacerbating existing skills shortages in the health sector.179 We discuss workforce implications further in section 8.5.2.3.

Vaccine requirements supported the elimination strategy and protected vulnerable people from COVID-19

While there is limited evidence that vaccination requirements produced substantial increases in vaccination coverage, the Inquiry recognises that – in 2021 – it made sense to require vaccination for workers at higher risk of being exposed to or passing on COVID-19.

The rationale for requiring vaccination was particularly strong in the case of border and health workers. For the first group, the rationale was similar to that for mandatory COVID-19 testing. Border workers were at higher risk of being exposed to COVID-19 – including new variants – due to their contact with people arriving from overseas. As long as Aotearoa New Zealand was pursuing an elimination strategy, requiring border workers to be vaccinated made sense in terms of reducing the risk of new chains of COVID-19 transmission entering the population. We cannot know how many ‘breaches’ of New Zealand’s border may have been prevented through such requirements, so it is not possible to evaluate the effectiveness of this measure.

Similarly, there is a clear case for requiring vaccination for workers interacting with medically vulnerable people – including those working in health and disability care and in residential aged care facilities. Again, it is not possible to assess how many cases of COVID-19 may have been prevented by these requirements. But it is clear that a key part of the rationale for health worker mandates was to protect vulnerable people from COVID-19 infection – including those who may not have been able to receive the vaccine themselves (due to medical contraindications).

8.5.2.2 Implementation issues

Medical exemptions to vaccination requirements were difficult to obtain

When occupational vaccine mandates were introduced in early 2021, workers could be exempted from the requirement on the basis of a certificate from a registered medical practitioner. This meant workers could continue to work in a role covered by a Government-issued vaccine requirement providing they presented a letter from their GP stating that there were valid medical reasons for them not being vaccinated.

This situation changed in early November 2021, when access to medical exemptions was tightened considerably. By this time vaccination mandates had been extended to the education and health and disability sectors, as well as frontline Police, Defence, and Fire and Emergency staff. From 7 November 2021 onwards, medical exemptions were issued centrally, under the authority of the Director-General of Health, on the basis of very limited criteria.180

Health officials recommended the exemption process be centralised in order to avoid people obtaining or demanding exemptions from healthcare practitioners in situations where they did not meet the relevant criteria.181 A small proportion of medical practitioners were known to have concerns about the safety of COVID-19 vaccines, and a group called New Zealand Doctors Speaking Out on Science (NZDSOS) had been vocal on this issue since April 2021.182 In August 2021 a general practitioner had contacted their patients noting that they did not support COVID-19 vaccinations (the doctor’s actions were found to be in breach of professional standards183). In the absence of a centralised system, it was not possible to monitor how many medical exemptions (appropriate or otherwise) were being granted, but the Ministry of Health had received complaints about practitioners allegedly issuing inappropriate exemptions.

It is possible that officials underestimated the scale of demand for medical exemptions that would arise with the expansion of vaccine requirements. A Cabinet briefing from October 2021 discusses the possibility of applications for vaccine exemptions being processed centrally by the Ministry of Health. The briefing states that ‘Provided the total number of exempted persons in the country remains in the low hundreds, the processing of the exemptions would not be overly administratively burdensome’ [italics added].184

In practice, 6,410 individual temporary medical exemptions were granted from vaccination requirements between 15 November 2021 and 26 September 2022.185

A considerable number of public submitters to our Inquiry expressed frustration about being denied a medical exemption, either on their own behalf, or someone else’s.

“I have two sisters that have health conditions and should not under any circumstance receive the vaccine, they were denied an exemption and told they should get their jab at the hospital in case they react and need to be revived. This is totally unacceptable from our government.”

“I worked in a school office and lost my job because I wouldn’t take the vaccine. […] I got a medical exemption only for the government to change the law on exemptions.”

Exemptions to prevent ‘significant service disruption’ were also possible, but controversial

Along with medical exemptions in very limited circumstances, it was also possible for employers to obtain temporary exemptions from vaccination mandate requirements on behalf of their staff. This measure was intended to prevent ‘significant service disruption’ to a critical health service where there were insufficient vaccinated workers available to allow the service to continue.

These temporary exemptions were applied for by employers (mostly district health boards), who had to show that a critical health service would not be provided unless they employed unvaccinated staff; that no alternative option was available; and that the organisation had done all they could to mitigate the risk of COVID-19 transmission from having unvaccinated staff.

According to information released by the Ministry of Health under the Official Information Act, a total of 478 applications for significant service disruption exemptions were received by the Ministry. Of these, only 103 were granted, covering approximately 11,005 workers.186 These were all for health services, and were temporary, the longest lasting eight weeks.187

This ‘11,000 exemptions’ figure featured prominently in the minds of some public submitters, perhaps reflecting a misconception that exemptions had been granted selectively, or a misunderstanding that these exemptions were some form of ‘medical’ exemption:

“I read that he [the Director-General of Health] thought there were less than 100 people in the whole of NZ that may be eligible for an exemption YET he approved 11,000 fellow MOH workers from it – how is this justified?”

It fell to employers in affected sectors to uphold Government-issued vaccine mandates

While central government issued occupational vaccination mandates by public health orders for border, education, health and disability, and frontline Police and Defence workers, it fell to employers in these sectors to enforce them. This involved notifying staff of the requirement, obtaining proof of vaccination from those who met it, and entering into an employment review process with any who did not.

While it is likely that some employers reached an accommodation with unvaccinated staff members through this process (such as keeping them on but requiring them to work from home), in many instances this would not have been possible. For example, with students back to full-time, in-person learning, it would not have been practical to ask teachers to work from home; nor was it feasible for frontline health or Corrections staff to work remotely.

Many employers in these sectors were ultimately required to terminate the employment of unvaccinated staff. The Inquiry has not seen figures on how many employees lost their jobs because of vaccine mandates, but representatives from many organisations and sectors told the Inquiry they had lost staff because of the vaccine mandate. This was challenging for many, as we heard from some of the stakeholders we engaged with directly. School principals and boards (usually made up of parent volunteers) may have found this particularly challenging.

“It came up often in peak body meetings. Many times we were asking for central direction because every individual school was having to interpret, based on often quite scant knowledge and limited understanding of compliance. Principals felt really vulnerable in that space because beholden to their communities, wanting to support workers, but equally keep their school operating. Quite big decisions.”

Occupational mandates were the subject of several High Court challenges in 2021 and 2022.188 While the Court upheld the mandates (except in the case of Fire and Emergency, New Zealand Police and New Zealand Defence Force staff), one of the judgments noted that ‘a more flexible approach to exemptions under employment arrangements may be more appropriate’.189

Arguably, some of the unintended social and economic harms arising from the Government’s occupational mandates (as detailed in the following sections) might have been reduced had the mandates allowed a ‘more flexible approach’ (for example, to reassign roles or grant extended periods of unpaid leave) as suggested by the Court.

8.5.2.3 Social and economic impacts

Some people lost income or employment as a result of vaccination mandates

We are not aware of any comprehensive data quantifying how many people lost their jobs because of non-compliance with a vaccination requirement (whether Government-issued or workplace-specific) during the COVID-19 response. However, a study undertaken by the New Zealand Work Research Institute in 2024 found workplace mandates had negative labour market impacts, including on unvaccinated workers’ overall employment rates and their earnings.190

Although the number cannot be quantified, people did lose employment due to vaccine mandates. A substantial number of public submitters to our Inquiry addressed this topic. Some shared first-hand experiences, while others talked about the impacts of mandate-related job losses more broadly. Many felt it was unfair and unnecessary for people to lose their jobs because they chose not to get vaccinated:

“I lost two jobs I loved, one being in healthcare and the other in hospitality. The stress and anxiety was very debilitating and not knowing what was going to happen as it progressed was so unsettling I nearly broke.”

“Devastation does not begin to cover what these people went through. The stories of loss were overwhelming. I spoke with couples who faced both earners losing their employment, rendering them unable to afford the basics, including food on the table and a roof over their children’s heads.”

Others did not have their employment fully terminated but still faced mandate-related consequences, such as being assigned different work or losing relationships with colleagues.

“My job was put at risk and I had a tense meeting with the directors and was no longer allowed onsite or to associate with my colleagues of 6 years.”

“I was reinstated in my job for a Government ministry, but the treatment by them has meant [I] no longer feel loyal or valued.”

Vaccination mandates exacerbated staff shortages for some sectors

We are not aware of any sources documenting how many people lost their jobs as a direct result of vaccination mandates. Nevertheless, we heard in many direct engagements that occupational mandates exacerbated existing staffing shortages in several key areas – including healthcare.

One district health board told us they had ‘lost 38 staff, including two doctors’, as well as ‘the only qualified audiologist’ they had. Following that person’s departure, a trainee audiologist saw patients, supervised remotely by a qualified audiologist based overseas. Similarly, a nursing organisation told us they had lost ‘about 35 people’ as a result of the mandates, noting ‘we couldn’t shift them to backroom functions as they still needed the vaccine […] there was nowhere for them to go’. Other health sector bodies talked about the disproportionate impact of vaccine mandates on small and remote communities, if the sole practitioner in that area was unable to work. We heard similar reports from other sectors, including early childcare.

Some of our public submitters also claimed particular sectors and professions – in health and education especially – had been damaged as a result of mandate-related job losses. Workers with much-needed skills had been ‘mandated out … at the very time when the country needed all hands on deck’, one wrote. We heard a number of direct accounts from submitters who were affected:

“I was mandated out of my 30 year nursing career, which led to the sale of my home.”

“My wife worked for [an ambulance service] and was mandated out of her job as she did not want to take a vaccine. This put further stresses on us financially, our family life, and I suspect pressure on the already understaffed [ambulance] service.”

Some submitters felt the mandates had undermined their long-term employment prospects. We heard from people who had undergone mandate-enforced termination and been re-employed once the mandate was lifted, but who now felt disillusioned and socially ostracised from their workplace.

Vaccine requirements provided assurance to some members of the public, although this reassurance may not always have been well founded

Aside from any impact on COVID-19 transmission or illness, vaccine mandates may have been seen as supporting the country’s economic recovery and a return to something approaching daily normalcy. In information supplied to our Inquiry about the evolution of the public health response, the Ministry of Health pointed out that one of the key benefits of vaccination certificates (and, by extension, other vaccine requirements) was the reassurance they provided to members of the public that it was relatively safexiii to return to indoor venues like bars and restaurants, hold gatherings of more than 100 people, and make use of close-proximity businesses like hairdressers and gyms. (We note, however, that from early 2022 this perception did not strongly align with the reality that vaccination offered limited protection from transmission, given Omicron was now the dominant variant.)

Some public submitters to our Inquiry supported this view:

“I supported having vaccines and agreed with the mandates, although I acknowledge the difficulties faced by those who chose not to be vaccinated and were unable to work. However, I was concerned for my own health and safety, so did not want an unvaccinated person to be at my place of work or at any of the services that I required (e.g. hairdresser, bus driver).”

Public reassurance may have been seen as particularly important during Aotearoa New Zealand’s transition away from an elimination strategy and towards the ‘minimisation and protection’ (suppression and mitigation) strategy. Given the scale of public concern at that time, it is understandable the Government sought to use vaccination requirements as a form of insurance as the country ‘opened up’. It is also understandable that the Government wanted to support employers in responding to staff concerns and managing the risk of COVID-19 transmission in the workplace.

At the same time, the justification for introducing vaccine mandates, and the associated limiting of people’s right to refuse medical treatment, focused on the role of vaccination in reducing COVID-19 transmission. While vaccination offered meaningful protection against transmission of Delta, protection was much weaker for Omicron. It seems likely that public understanding of this distinction was limited at the time, which may have contributed to the expectation that workplace vaccination requirements were protecting people from infection with COVID-19. Some stakeholders felt that vaccine messaging was slow to explain the evolving evidence (i.e. that vaccination was no longer particularly effective in limiting COVID-19 transmission), and told the Inquiry that this ‘disconnect’ fuelled distrust in Government. The Inquiry notes that – should a similar situation arise in a future pandemic (i.e. that vaccines become less effective in reducing transmission) – it will be important for public messaging to be agile in reflecting the changing science.

Some unvaccinated people felt ostracised, lost relationships and/or were unable to access certain locations and services, including some types of healthcare

The public submissions we received gave an insight into the experience of being unvaccinated during the pandemic. As well as being unable to use many public places and services, submitters described unvaccinated people feeling shunned by their communities, workplaces and even their families due to their unvaccinated status.

“It was ridiculous to not be able to take my grandchildren to the public library as well as other places. I was definitely discriminated against for not being vaccinated.”

“[Vaccine mandates] destroyed the latter years of my family’s life. Mandated out of RSA. Bars, Car and Motorcycle clubs, visit to retirement homes and family around country. Can’t even get coffee and cake at cafe in town...”

In some cases, submitters said unvaccinated people were effectively ostracised by society – treated as if they were selfish, responsible for spreading COVID-19, and to be avoided. At a personal level, being unvaccinated could strain and even destroy family relationships. Submitters described couples divorcing, unvaccinated grandmothers being prevented from seeing their grandchildren, and lifelong friends who would no longer speak to them.

“Due to mandates I was excluded from my family Xmas, not allowed to attend my sisters 50th or my father’s 80th birthday. This has had a devastating and lasting effect on my relationship with my family.”

Other submitters reported difficulty accessing healthcare during the pandemic because they were not vaccinated.xiv It is important to note that it was not permitted for essential services (including primary healthcare) to require vaccination certificates for entry. However, the strict protocols adopted by many services, such as seeing unvaccinated patients in their cars or delaying routine visits, made some people feel as though they could not access basic services.

“I was basically trespassed from my doctor’s office which meant I was not able to receive my healthcare needed for my own disability. I was told that face to face was impossible because of my decision. I was denied healthcare. When I did see someone it was in the car park. I pay for these visits I am entitled to healthcare.”

“Unable to have a breast ultrasound [and] checkup with my private surgeon. Nevertheless 2 months later, she saw me in the public hospital! What was the difference?”

For some, the consequences of not being vaccinated or having a vaccine pass – threatened or actual job loss, social ostracism, being unable to enter certain places – left them feeling they were being coerced (by employers or the Government) to get vaccinated. While vaccination was voluntary (in that people had to consent to receive it), some submitters clearly felt as though this ‘choice’ was not a real one.

“I felt bullied into taking the COVID 19 vaccine in order to keep my job and to be treated like a sensible, law abiding, caring, normal person in NZ society and to be able to receive and use basic services.”

“When the previous Prime Minister Chris Hipkins said recently ‘there was no compulsory vaccination, people made their own choices’ is an absolute insult. My husband’s choice was to resign as he was forced out of his employment.”

“I felt pressured in to getting the vaccine even though I didn’t feel comfortable […] For a long period of time [it] felt like our country was and government was a dictatorship.”

While many public submissions describing the negative impacts of vaccine mandates were from people who told us they had chosen not to get vaccinated, we also heard from people who had themselves been vaccinated but who lamented the harm the mandates had caused by stigmatising others and damaging relationships. Many people who submitted to the Inquiry expressed grief and anger over divisions they said the mandates had caused, describing families and friends who were ‘torn apart’ or ‘split’ over the issue, and strained relationships that had never been repaired.

“I found the division between my friends and colleagues astounding.”

“It caused fractures between our families and friends that have yet to mend.”

“The division created between vaccinated and non-vaccinated was cruel and unusual […] There is anger and trauma still remaining to this day and distrust in authority is evident.”

Workplace specific vaccination policies caused some confusion

We saw evidence suggesting employers were concerned about their legal risk if employees were exposed to COVID-19 in the workplace and were inclined to put vaccination policies in place as a result.191 Some businesses (as well as unions) were also concerned about the risk to other employees who might be obliged to work alongside unvaccinated colleagues.

All this led to considerable uncertainty about what employers – and public sector agencies that had not been deemed essential services – should do. In our engagements, some said they wanted directives and clarity from Government, rather than guidance that put the onus on them to make their own assessments and policies. We also heard that some employers and governance bodies were concerned about their exposure to potential litigation if they did (or didn’t) require employees to be vaccinated, and sought legal advice.

Vaccination mandates contributed to a loss of trust in some communities

The Inquiry heard from a range of stakeholders that vaccine mandates had undermined trust in some communities, particularly among Māori. Many stakeholders (including health and education providers) spoke about how they were ‘still feeling the effects of the mandate’ in terms of a loss of engagement and trust among whānau.

Health providers felt the mandates had caused many people to disengage from the system and had even decreased the likelihood that some groups would take up vaccination. Several spoke of Māori experiencing this as a loss of their agency, exacerbating mistrust of the health system:

“We need to rebuild trust between Māori and the health service... People were wanting to maintain mana Motuhake and self-determination. The vaccine mandate meant people left the health sector and some people are reluctant to re-engage with health services. We need to create and rebuild trust with communities, trust with services.”

Several stakeholders linked the vaccine mandate with decreased uptake of childhood vaccinations since the pandemic. A member of a hospital senior leadership team said:

“The COVID vaccination journey has left an enduring bruise on vaccination for New Zealand, moving forward… [the result of people] being forced to [undergo vaccination], versus “let’s have a conversation”. There was a loss of trust. The vaccine mandates caused lasting harm.”

Another member of the same leadership team talked about the ‘unintended cost’ of vaccine mandates in terms of decreased uptake of key childhood vaccines and a consequent increase in the risk of diseases such as measles and whooping cough. The team made a direct link between the vaccine mandate and a loss of social cohesion and trust within the community they served, particularly among Māori. Other team members talked about a ‘huge erosion of trust’ among many whānau that would continue for years to come:

“There’s a whole generational impact. A whole generation that won’t trust [the health service], as a result of the mandates.”

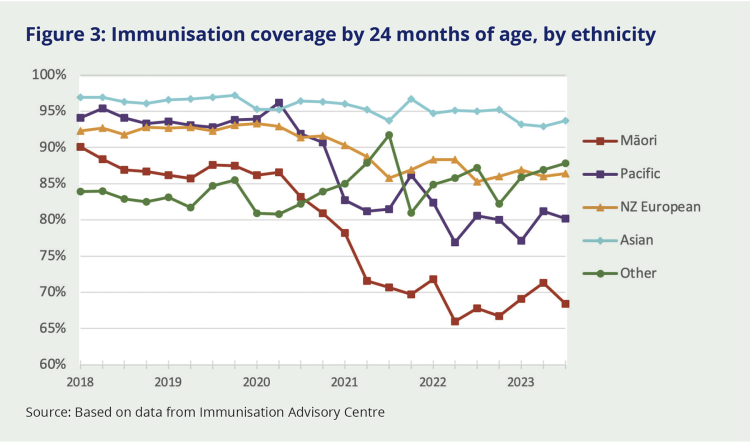

Official data confirms a drop-off in childhood vaccination levels since the pandemic, with pronounced declines among Māori and Pacific children – for whom vaccination coverage at 2 years has declined from over 90 percent in the pre-pandemic period to 80 percent (for Pacific) and 68 percent (for Māori)xv (see Figure 3). These changes reflect several pandemic-related factors, including decreased access to WellChild visits during the pandemic. Other countries have also experienced declines in uptake of childhood immunisations, due in part to reduced healthcare contact during the pandemic.192 There is global evidence of falling public confidence in vaccines, which may be linked to the spread of vaccine misinformation and disinformation during the COVID-19 pandemic.193

Figure 3: Immunisation coverage by 24 months of age, by ethnicity

Source: Based on data from Immunisation Advisory Centre

We note there are particular risks to social cohesion and trust from the use of vaccine passes that create a ‘dual system’ of entry to spaces and social gatherings. While these risks were known and communicated to decision-makers at the time, they were perhaps even more pronounced than was understood prior to the COVID-19 response. We return to these matters in the next section.

xi There was also a positive synergy from vaccination that was theoretically known at the time. In addition to providing a modest reduction in a person’s chance of becoming infected with Omicron (as was shown in studies available in early 2022), vaccination was also likely to modestly reduce the chance of an infected person passing the virus on to someone else (a benefit that was expected at the time, but not demonstrated until later in 2022). The combination of these two mechanisms meant that vaccination would still have had some impact in dampening Omicron transmission.

xii For some infectious diseases (such as measles), even a modest increase in vaccination coverage can significantly reduce the risk of sustained community transmission and prevent outbreaks from occurring. Unfortunately this is not the case for COVID-19 since immune protection (from either vaccination or previous infection) wanes fairly quickly. This means a proportion of the population will be susceptible to infection at any given point in time, even if total vaccine coverage is high.

xiii We say ‘relatively’ safe because it was clear from early in the rollout that the available vaccines could not eliminate the risk of contracting or passing on COVID-19, nor guarantee that a vaccinated person would not become seriously unwell if they contracted the virus. They could – and did – however, reduce the risk on both scores (waning effectiveness against the Omicron variant notwithstanding).

xiv Most were commenting on primary healthcare (GP visits or routine screening) or dental care.

xv The most recent estimates of coverage are from September 2023