3.3 Our assessment Tā mātau arotake

3.3.1 Aotearoa New Zealand’s use of lockdowns during the COVID-19 pandemic, while stricter than many countries, was comparatively sparing in terms of time spent in lockdown conditions

We start our assessment of the use of lockdowns by acknowledging that, during the first couple of months of the pandemic response, decision-makers were dealing with very high levels of uncertainty. The situation at that time required a different kind of risk tolerance than later in the pandemic, when developments such as the availability of vaccines and greater understanding of the effectiveness of public health measures had significantly changed the pandemic landscape. This should be taken into account as part of the context within which the use of lockdowns occurred.

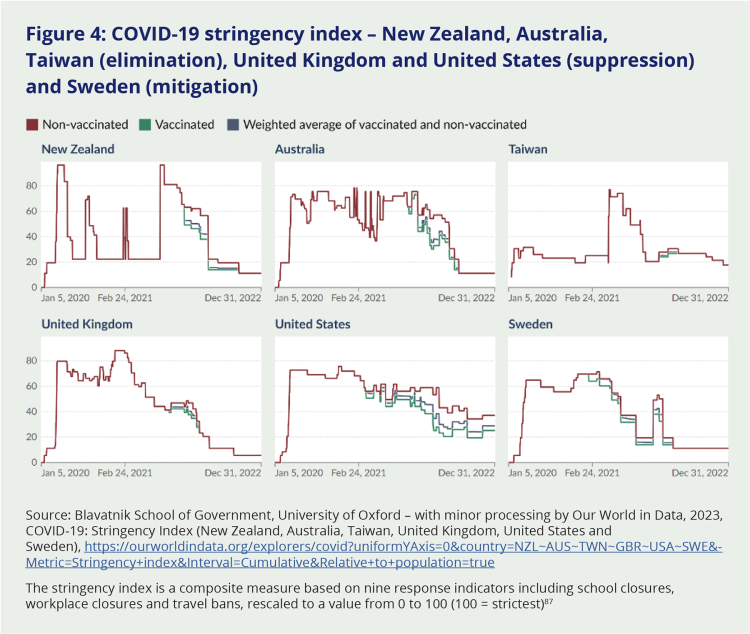

How Aotearoa New Zealand’s use of lockdowns compared with other countries is demonstrated in the COVID-19 ‘stringency index’, developed by University of Oxford researchers to compare the strictness of national COVID-19 responses across the world.81 Based on policies in nine areas (public information/advice, gathering restrictions, cancellation of public events, restrictions on movement, stay-at-home requirements, workplace closures, school closures, closure of public transport, and border/international travel controls), countries were given a stringency score between 0 (no restrictions) and 100 (maximum restrictions). Figure 4 shows the changing stringency score for a selection of jurisdictions – including New Zealand, Australia and Taiwan (all of which followed an elimination strategy), the United Kingdom and the United States (which used suppression for much of 2020–22), and Sweden (which pursued a mitigation strategy).v

Under Alert Level 4 (full lockdown) Aotearoa New Zealand’s control measures were at the top of the scale, stricter than other countries. But New Zealanders spent comparatively little time under these conditions.82 After the initial lockdown, Aotearoa New Zealand spent much of 2020 and the first half of 2021 at Alert Level 1. During these periods, people faced far fewer domestic restrictions – outside international border restrictions affecting their ability to travel or, for some, to return home – than many other countries, including those pursuing suppression or mitigation strategies. As a result, New Zealanders were able to attend large-scale events such as concerts and sports matches.

Very few countries avoided using mandatory lockdown-type measures as part of their COVID-19 response. Remarkably, Taiwan managed to eliminate COVID-19 transmission in 2020 without a lockdown by mounting a rapid and highly effective public health response – including strict border restrictions, isolation and contact tracing, alongside widespread use of facemasks.83 Previous experience with SARS (in 2003) meant mask wearing was widely normalised in Taiwan, which also had well-developed pandemic response capability.

Taiwan also made use of extensive electronic monitoring – including tracking of people’s cellphones – to ensure compliance with isolation and quarantine restrictions.84 While lockdowns were not mandatory, most people in Taiwan did dramatically reduce their mobility achieving nearly the same effect as a mandatory lockdown.

Several Pacific Island nations – including Samoa, Tonga, the Solomon Islands, Tuvalu and Tokelau – protected their populations by closing their borders before any cases of COVID-19 had reached them (i.e. an exclusion strategy).85 These countries were able to avoid stringent domestic measures such as lockdowns, since they were cut off from any source of infection. Some of them managed to remain ‘COVID free’ for several years (for example, Tokelau had still not experienced a single COVID-19 case by June 2022).86 While border closures protected these islands from the potentially devastating effects of infection, they also carried massive social economic impacts – particularly for those whose economies relied heavily on tourism.

Figure 4: COVID-19 stringency index – New Zealand, Australia, Taiwan (elimination), United Kingdom and United States (suppression) and Sweden (mitigation)

Source: Blavatnik School of Government, University of Oxford – with minor processing by Our World in Data, 2023, COVID-19: Stringency Index (New Zealand, Australia, Taiwan, United Kingdom, United States and Sweden), https://ourworldindata.org/explorers/covid?uniformYAxis=0&country=NZL~AUS~TWN~GBR~USA~SWE&-Metric=Stringency+index&Interval=Cumulative&Relative+to+population=trueThe stringency index is a composite measure based on nine response indicators including school closures, workplace closures and travel bans, rescaled to a value from 0 to 100 (100 = strictest)87

3.3.2 Aotearoa New Zealand would have been less reliant on lockdowns to eliminate COVID-19 infection if there had been greater prior investment in its core public health tools, capacity and capability

As discussed in Chapter 5, Aotearoa New Zealand’s health system (as in many other countries) needed to rapidly scale-up its core public health tools – such as contact tracing,case isolation and in-country quarantine – to meet the demands of the COVID-19 response. Likewise, it needed to significantly strengthen the capacity and capability of the public health system. Had there been greater investment in these areas before COVID-19 arrived, decision-makers might have had more options to limit the spread of the virus. Later, uneven implementation of other parts of the pandemic response (such as the vaccine rollout, which took longer to reach different population groups; see Chapter 7) also reduced the range of options available to decision-makers.

With their options limited, decision-makers had to rely more heavily on lockdowns to reduce the spread of the virus than might otherwise have been the case. For example, as outlined earlier, Taiwan – which had well-developed public health infrastructure prior to the arrival of COVID-19 – was initially able to eliminate viral transmission without resorting to lockdowns.88 In our view, if Aotearoa New Zealand had benefited from similar investment in key public health tools, capacity and capability – and if the uptake of other measures such as mask wearing had been more widespread – it might have been possible to eliminate COVID-19 transmission early in the pandemic with less reliance on lockdowns.

3.3.3 Deciding when to start and end public health and social measures such as lockdowns is challenging and requires difficult trade-offs in the face of uncertainty

Deciding when to end lockdowns was extremely challenging. Decision-makers had to balance the aim of protecting people from COVID-19 against the growing social and economic impacts of requiring large parts of the population to remain under tight restrictions. While vaccination reduced the risks associated with COVID-19 infection, the picture was complicated by the different rates of vaccine coverage across different population groups, particularly the lower levels of vaccination for Māori and Pacific peoples (covered in more detail in Chapter 6).

There was no established methodology or approach to inform decision-makers of the optimal time to move away from using lockdowns as a primary public health management tool – and indeed in a future pandemic, it would be challenging to develop a formulaic approach as there are so many moving parts and the context constantly changes. While the Government had indicated that reaching a target of 90 percent vaccination coverage across each region was the likely trigger for ending lockdowns,89 subsequent advice placed much greater focus on the need to protect vulnerable communities – including Māori and Pacific communities.

When it came to ending the use of lockdowns, decision-makers were receiving advice on a range of factors, including: vaccination levels, evolving evidence on vaccine protection, reducing social licence and the experiences of other countriesvi as they relaxed public health and social measures.90 The advice was also informed by modelling that took account of vaccination coverage, use of public health measures, and the strength of testing, contact tracing and isolation systems. Regarding the Delta outbreak and late-2021 Auckland lockdowns, international evidence was emerging that showed vaccine-related protection from COVID-19 transmission started to wane some weeks following vaccination.91 Officials were aware of this, and the Inquiry understands that waning immunity was included in models from January 2022 to help inform decisions about management of the Omicron outbreak.92 From evidence the Inquiry has seen, waning immunity was not included in modelling prior to January 2022.

Time lags are also a factor that needs to be considered when it comes to deciding whether or when to relax public health and social measures. Relaxing them raises the risk that the virus will start taking off (again). But that will take time to happen. Although it is a delicate balancing act, it is possible to relax public health and social measures while still completing a vaccination rollout – and then catch any resurgence as or if it arises. For example, in late 2021 – when Delta was the dominant COVID-19 variant – the Australian states of Victoria and New South Wales released lockdowns with lower population vaccination levels (around 70 percent)93 without any associated increase in case numbers.

The final decision on when to transition to the ‘traffic light’ system (and move out of lockdowns) was a judgement call. It was based on a range of considerations, all of which had a degree of uncertainty. In making this decision, Cabinet had to balance many different outcomes and impacts – health, social and economic – as well as equity considerations. While some senior ministers we spoke to thought that, in hindsight, the last round of Auckland lockdowns perhaps went on too long, others felt that the need to protect equity in health outcomes meant they could not have made any other decision.

Ultimately, decisions to lift public health and social measures will always be judgement calls. We consider it essential that the fullest range of information is provided to decision-makers so that they can consider tradeoffs and make decisions based on the best information available at the time. Transparency of this information with the public, and justification of how the decisions were made, is also essential.

3.3.4 There was confusion and frustration around the ‘essential services’ designation, which some felt was discriminatory and unfairly harsh

A theme in public submissions was that the ‘essential’ designation was sometimes confusing, and that ‘essential services’ should have been more clearly defined and communicated. We heard similar frustrationsvii directly from stakeholders. Submitters and stakeholders often reflected a view that central government did not understand the operational realities of essential industries and their workers. A particular concern was that the designation undermined competition and disadvantaged smaller businesses – for example, by allowing major supermarkets to open but not small-scale food providers such as butchers and produce stalls.

There was criticism that the Government was both indecisive and imprecise over what were essential services.

“Decisions made by the Government need to be substantiated by the evidence and the science which under-pinned those decisions e.g. why was it considered safer for supermarkets serving many people at a time to stay open than for small food supply businesses, which could easily limit customers to one or two at a time?”

Public submission to the Inquiry

At Alert Level 4, the scheme did not allow ‘safe’ work where there was little risk of viral transmission (for example, people working outdoors on their own, such as bulldozer drivers). There was little flexibility for employers to apply judgement at the margins as to what was essential or safe work. We heard from representatives of the forestry, road construction and non-food manufacturing sectors, for example, that they believed parts of their sector could have operated safely, helping to reduce the economic and social impacts of lockdown. It is likely that such constraints imposed unnecessary economic costs, both immediately and over the long term, for little health benefit.

It is also possible that some businesses misused the ‘essential service’ designation to require staff to be onsite when this was not necessary or appropriate under Alert Level 4 conditions. Unions (which were confirmed to be essential services when representing their members at work) told us this was a common problem.

3.3.5 Essential workers reported challenging experiences

Workers in essential services continued to go to work during lockdown, putting themselves at risk of exposure to the COVID-19 virus,viii and sometimes taking extraordinary measuresix to protect their families.94 They encompassed a wide variety of professions, from specialist health providers to sign language interpreters, port workers to checkout operators, prison staff to journalists. Many worked in low-wage or blue-collar jobs in retail, transport or sanitation.95

More than a quarter of our public submissions came from essential workers. Some were celebrated and praised for their efforts and sacrifices during the pandemic (particularly healthcare workers, mirroring the daily applause rituals thanking frontline health workers around the world). Leaders from a major supermarket chain told us ‘the community respected our staff – we got brought home made baking […] our staff were proud of their contribution’. One port worker commented that ‘it was interesting to be seen as essential – it was a change in perspective compared to most people’s view of waterside workers’.

Others though – or even the same workers at different times – faced abuse, anger, fear, discrimination or distress from the public. Incidents of people intentionally spitting at essential workers were reported.96 One public submitter described the impact in these terms:

“The first day of the first lockdown we had to call police three times, got spat in the face, called an ambulance and a glazier. That was just day 1.”

Essential workers were praised for their efforts and sacrifices. But the Inquiry also heard of essential workers being stigmatised due to fear of infection.

Some described fearing for their safety, and a lack of protection and support to manage their risk of COVID-19 infection and transmission. However, we also heard from essential workers who were proud of their efforts and pleased to have been part of the pandemic response:

“Overall it felt like a privilege to still be working when so many others could not. It allowed us to retain a sense of structure and normality, and to feel as though we were contributing something useful.”

Thanks in large parts to the efforts of these workers, during Alert Levels 3 and 4, the ‘essentials’ of life – sufficient food supplies, functioning lifeline utilities, a sound financial sector, supply chains, health and emergency services, access to courts and public safety – were fundamentally maintained. While international supply chain congestion caused problems, at a national level there were no shortages of food and essential goods (although there was some panic buying and product shortages early on – especially of toilet paper and flour). Lifeline utilities continued to function and there were no concerns about a shortage of fuel.97 Courts remained open through COVID-19, adapting as required to operate safely while also ensuring that access to justice, fair trial and other rights were maintained as far as possible in the circumstances.

“Overall it felt like a privilege to still be working when so many others could not. It allowed us to retain a sense of structure and normality, and to feel as though we were contributing something useful.”

Public submission from an essential worker

Spotlight: Impact of lockdowns on business | Ngā pānga o ngā noho rāhui ki ngā pakihi

Depending on the alert level in place, the daily challenges which businesses faced in lockdown could include whether they were allowed to operate at all and if so, under what conditions; whether their suppliers could operate and deliver needed goods and services; whether they still had customers; were staff members healthy and able to work; were they as business operators healthy, and were their families okay.

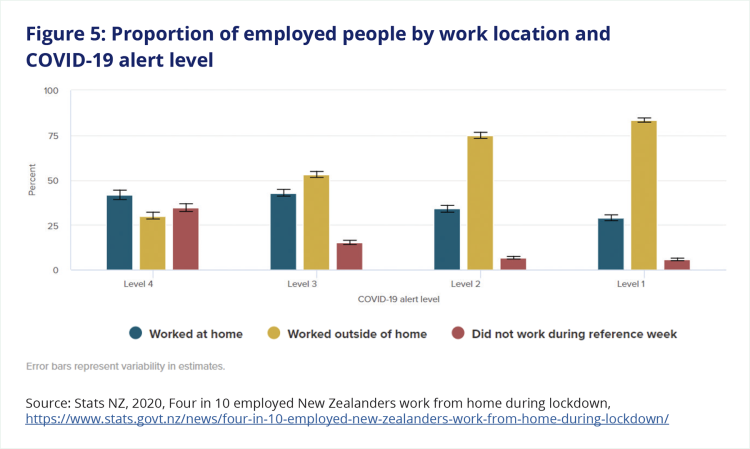

When the first Alert Level 4 national lockdown started on 23 March 2020, 30 percent of employed people could work outside home while 42 percent of people were able to work from home. Another 35 percent had jobs or businesses but did not work during that week.98

Figure 5: Proportion of employed people by work location and COVID-19 alert level

Source: Stats NZ, 2020, Four in 10 employed New Zealanders work from home during lockdown, https://www.stats.govt.nz/news/four-in-10-employed-new-zealanders-work-from-home-during-lockdown/

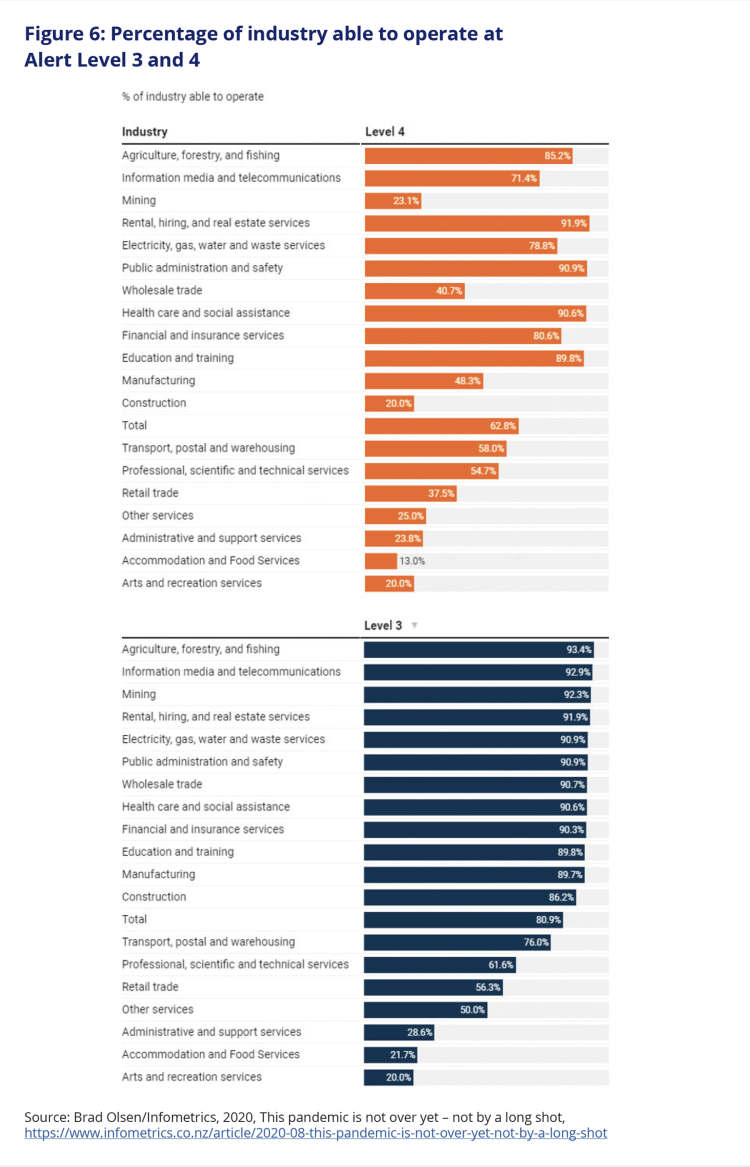

The different levels of lockdown also affected the level of industry activity in ways that varied across sectors. For agriculture, moving from Level 4 down to Level 3 saw normal activity increase from 85.2 percent to 93.4 percent, but for the accommodation and food sector, normal activity grew from 13 percent to 21 percent.99

Figure 6: Percentage of industry able to operate at Alert Level 3 and 4

Source: Brad Olsen/Infometrics, 2020, This pandemic is not over yet – not by a long shot, https://www.infometrics.co.nz/article/2020-08-this-pandemic-is-not-over-yet-not-by-a-long-shot

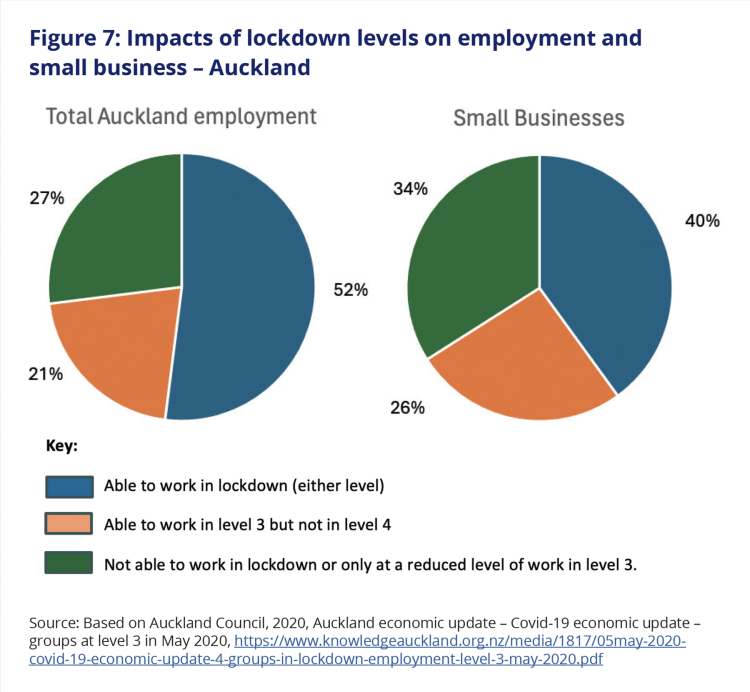

Meanwhile, analysis undertaken for Auckland Council in 2020 showed the impact of different alert levels on specific groups of workers. While overall activity increased with the move from Level 4 to Level 3, 34 percent and 31 percent of small business employees and the self-employed respectively remained unable to work in the Level 3 lockdowns, compared to only 27 percent of all employed people in Auckland.100

Figure 7: Impacts of lockdown levels on employment and small business – Auckland

Source: Based on Auckland Council, 2020, Auckland economic update – Covid-19 economic update – groups at level 3 in May 2020, https://www.knowledgeauckland.org.nz/media/1817/05may-2020-covid-19-economic-update-4-groups-in-lockdown-employment-level-3-may-2020.pdf

3.3.6 Impacts on business were mixed

Prominent business leaders were amongst the first to urge, and then support, the lockdowns, and we heard that many parts of the response – including lockdowns – were initially seen as positive by businesses. However, over time some felt that the consequences of lockdowns on businesses were not adequately mitigated (for more on the economic response and impacts, see Chapter 6).

For some businesses the lockdowns, and the rules about who could operate, led to increased debt, mental health issues, and in some cases the closure of their business. We heard frequent reports of hardship for businesses not able to operate during Alert Level 4 – such as butchers, hospitality and restaurants – with this hardship extending to some employees and suppliers. CBD businesses were also hit hard, as were some sectors such as tourism and some parts of hospitality. Many saw the restrictions as unfair (for example, allowing supermarkets to operate but not some of their competition). In general, large businesses were more able to absorb the financial shock than small businesses.

As the different waves of COVID-19 impacted Aotearoa New Zealand with further national and regional lockdowns, business confidence became increasingly shaky due to ongoing uncertainty, and price inflation. Small businesses that had used their reserves during previous lockdowns increasingly wondered if it would remain viable for them to keep operating.101

The impact of lockdowns was particularly felt by small businesses, with many sectors impacted, including tourism, retail, hospitality, personal services and trades. We were told that, despite (welcomed) government support measures, many small businesses faced challenges as to their future viability. Small business balance sheets suffered, and many increased home mortgages to keep their businesses afloat.

“The first lockdowns had many business owners facing complete uncertainty and fear regarding completely losing their business, their customers, their ability to produce, their staff, their personal homes (which most often financially guarantee such businesses), their life’s work, and their future...”

Small business owners noted the mental health repercussions for both the business owners and their employees of not being able to operate during lockdowns. For small business owners from ethnic minorities this was exacerbated by factors such as communication difficulties and a lack of awareness of supports. Other representatives of small business noted the combination of the financial effect of lockdowns and subsequent higher interest rates on business viability. There were concerns about the lack of confidence from the impact of cumulative lockdowns.

While some sectors were well positioned to work digitally during lockdowns (e.g. banking and finance, technology sectors in general), others simply could not operate in this way (e.g. construction). For businesses that were able to continue to function, there were still issues to deal with, including how to keep staff shifts separate, integrating social distancing into operations, and mental health issues for staff.

3.3.7 Some people faced particular difficulties in lockdown

While lockdowns contributed to increased anxiety and stress for many people, there were some for whom this was particularly challenging. For those with existing mental health issues, this increased stress was a significant issue. Women and children at risk of violence due to the heightened stress had reduced opportunities to seek support. Disabled people and older people relying on in-home care faced significant challenges in getting appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE) and maintaining adequate levels of care.102 See Chapter 6 for more examples.

3.3.8 Working from home posed its own challenges

People who were employed, but not designated essential workers, were required to work from home if they could during Alert Level 3. This posed a different set of challenges. While some workers and employers were well-equipped to make this happen, others were not. We heard frustration from submitters that the Government seemed to assume that most people could work from home comfortably when this was not the case for all. There were issues with adequate technology, internet access, cramped or inappropriate workspaces, distractions and competing domestic demands.

The difficultly of working from home while trying to supervise children and support them with remote learning has been well documented publicly and by researchers.103 Going into the pandemic, the vast majority of unpaid work was performed by women, particularly caring and community roles. The pandemic placed many with significant caring responsibilities (most often women) under considerable additional stress.104 During the Alert Level 4 lockdown in 2020, women were more likely to report a significant increase in caring demands.105 These effects were felt by a range of women, including young women who picked up additional care responsibilities in their household during the pandemic.106

We heard from submitters that the additional stress placed on working parents (and others juggling significant care demands) was not well acknowledged. This applied to the government response (for example, no provision of childcare at Alert Level 4), and the actions of employers (for example, not adjusting workloads to take into account additional domestic responsibilities). The difficulties of juggling these competing demands, as well as the social disconnection of working from home, took a toll on many people’s mental health.x

“Trying to work an 8-hour day, while assisting kids with homeschool was nearly impossible. Essential workers working outside the home could access childcare but parents working from home could not. Finding a way to better support all types of households in the future would be advisable.”

However, there were also benefits from the increased flexibility of working from home, the availability of new digital tools for work, connection and collaboration, and the normalisation of hybrid work. Some submitters appreciated how the pandemic normalised working from home, while others celebrated the innovation this requirement had prompted.

“I run my own Personal Training business, the pandemic challenged me to embrace technology and grow my business online which I never would’ve done otherwise. I’ve now incorporated that into my business today.”

3.3.9 People in informal and precarious work were hit hard

Many people undertake (or commission) some informal work in normal, non-pandemic circumstances: tradespeople do cash jobs, people pay family members to babysit, a stay-at-home parent might clean one or two houses while their children are at school. For some, this supplements their main income, while for others, it is their income.

Such informal economic activity is sometimes referred to as the ‘grey economy’. Like everything else, much of this kind of work stopped during Alert Level 4 lockdown in the early phases of the pandemic, and people undertaking it were not eligible for the wage subsidy or income relief payments. Because it is informal and undocumented, and operates outside the tax net, it is very difficult to know how many people lost income this way and what the impacts were.

We also heard from some stakeholders and submitters that people in precarious employment were a particularly vulnerable group. This included people whose employment was too inconsistent to qualify for income support, casual sub-contractors, and workers whose employers didn’t apply for the wage subsidy but instead closed or laid off staff (for further discussion on economic supports, see Chapter 6).

Our engagements with officials involved in designing COVID-19 income protections and employment support suggested little consideration was given to these issues.

3.3.10 There were significant educational impacts, but these were likely in keeping with those experienced worldwide

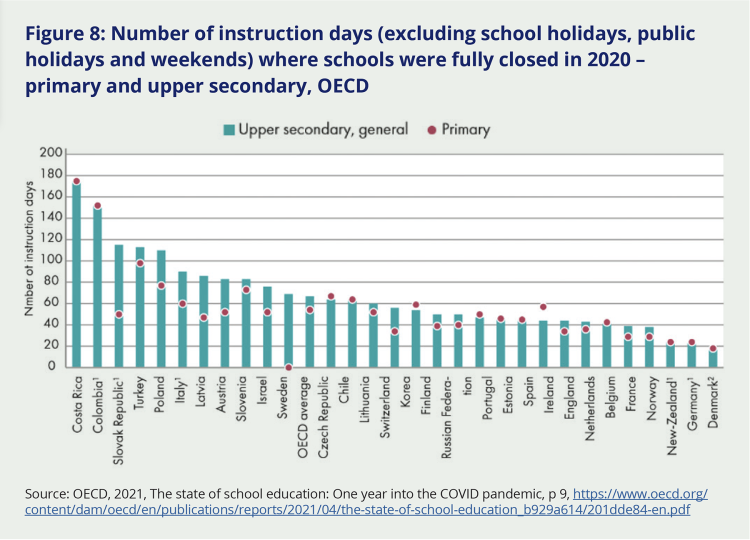

While the disruption to education for students in Aotearoa New Zealand was less than in most other OECD countries, it still had a significant and negative impact – particularly for Māori and Pacific students, those from lower socio-economic backgrounds, and likely for students in Auckland.

By the end of 2020, and up until mid-2021, the elimination strategy had served Aotearoa New Zealand school students well in terms of minimising the interruption to their education. Relative to other countries, students here missed fewer days of school instruction in 2020, with the third lowest number of days closed in the OECD.107

Figure 8: Number of instruction days (excluding school holidays, public holidays and weekends) where schools were fully closed in 2020 – primary and upper secondary, OECD

Source: OECD, 2021, The state of school education: One year into the COVID pandemic, p 9, https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/publications/reports/2021/04/the-state-of-school-education_b929a614/201dde84-en.pdf

The impact of school closures on student achievement and academic progress was not immediately clear, but later, in the first PISA studyxi since the start of the pandemic, covering the period from 2021-2022, Aotearoa New Zealand’s maths scores were 15 points lower than in 2018 (as was the OECD average), while New Zealand’s reading and science scores were largely unchanged from 2018 scores.108 In all three, New Zealand maintained its relative position compared to other OECD nations, suggesting New Zealand students experienced loss of learning from the pandemic, particularly in maths, but no more so than in other comparable countries.109 Students from low socio-economic backgrounds had a larger drop in maths than more socio-economically advantaged students.110

Looking back at the cumulative impacts of the pandemic, a 2023 ERO report found significant, concerning, and ongoing impacts on learners’ progress.111 These mostly exacerbated existing trends and were in line with global experience. They included:

- A serious impact on attendance. Regular school attendance in Aotearoa New Zealand dropped as low as 40 percent in Term 2 of 2022 and remains low. By the end of 2022, regular attendance had only recovered to 51 percent, suggesting COVID-19 disruptions have led to longer-term impacts on attendance.

- Challenging behaviour – 41 percent of principals reported behaviour was worse than they would previously have expected for the time of year (they were surveyed in March).

- Progress and achievement – nearly half of principals in 2023 said learning was worse than would previously have been expected. Principals in schools serving poorer communities are more than three times as likely as those serving better-off communities to say that their learners are behind by two or more curriculum levels.

- NCEA levels had fallen to below where they were at in 2019.

- Learners in poorer communities, Māori and Pacific students were more impacted.xii

In the tertiary sector, qualification, course completion rates and first year retention rates remained fairly stable through the pandemic period, compared to 2019.112 However, there is evidence that some groups have been more impacted than others. There have also been well-documented impacts on the wellbeing of educators and staff at all levels.113

Students in Auckland experienced more significant disruptions to their education than those in the rest of the country. For most of the country, school closures were limited to five weeks in March and April 2020, two weeks in August 2020, and three weeks in August 2021. But Auckland schools were closed for an additional 15 weeks in the second half of 2021. There is no strong evidence about the specific regional educational impacts of Auckland’s multiple lockdowns. But there was already emerging evidence in early 2021 that student engagement there was more affected, with 26 percent of Auckland teachers reporting that their learners were engaged, compared to 51 percent outside of the region.114

In a report released in June 2021, the Ministry of Education found that, nationally, learning progress in reading and maths for many student groups was ‘essentially unchanged or even positive’ compared with 2019. When this data was updated in mid-2022, the Ministry said they showed ‘that the effects of Covid-19 on learning progress were not severe’.115

A considerable number of submissions raised concerns about the disruptions lockdowns caused to children and young people’s education, and specifically the impact of this on their mental health. Submitters thought the social isolation caused by school closures had contributed to multiple impacts on young people, including increased anxiety, impaired communication and social skills, and a trend towards disengagement from education. These observations from submitters are supported by other evidence showing a disproportionate impact of the pandemic on child and youth mental health, including surveys of children and young people themselves, academic research, and data about demand and call volumes for child and youth mental health services and support.116 Not all of this can be directly attributed to the closure of educational facilities, but this was clearly a contributing factor, especially in relation to high rates of loneliness and social isolation among young people. See Chapter 6 for more on the pandemic’s impact on mental health and wellbeing.

Some residents felt South Auckland was unfairly stereotyped and that COVID-19 outbreaks occurring elsewhere did not receive the same negative coverage.

3.3.11 Auckland – especially South Auckland – did it tough

The cumulative impacts of repeated lockdowns on Aotearoa New Zealand’s largest city were multifaceted, encompassing economic, mental health and wellbeing, educational outcomes and social cohesion.

Maintaining the trust of South Auckland communities was important. These communities – with their high proportion of essential workers, many of whom worked in or around Auckland Airport – were disproportionately impacted by repeat outbreaks and lockdown requirements. There were high levels of fear and anxiety within these communities, and we heard about older people reluctant to leave home and families keeping children away from school even when restrictions were lifted. Public health messaging about ‘bubbles’ and limiting purchases of grocery items impacted large households with multigenerational families who shared resources or provided care for elderly family members in other households. There was also evidence of children with disabilities left without carer support.117 None of these challenges were unique to South Auckland, but they appear to have been particularly concentrated there. South Auckland community providers told us that the COVID-19 response did not always anticipate or address unintended consequences such as these.

An unfortunate public narrative also emerged whereby South Auckland was regarded as more likely than other areas to host an ‘out of control’ outbreak requiring aggressive alert level changes. Community leaders felt this narrative was based not only on population density, but on negative preconceptions about the population in that part of Auckland. Some residents felt South Auckland was unfairly stereotyped and that COVID-19 outbreaks occurring elsewhere did not receive the same media coverage.118

v Note that these graphs reflect the most stringent location in each country. For example, New Zealand’s 2021 stringency score largely reflects what was happening in Auckland, with most other regions experiencing comparatively few restrictions.

vi Countries included Australia, Singapore, Iceland, France, Israel, Denmark, Norway, the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada and Germany.

vii For example, from Infrastructure New Zealand: ‘There was a significant lack of clarity as to the definition of essential services. It was obvious this had not been thought about prior to the lockdown and rules and definitions were being developed under urgency with less than perfect information.’

viii Between 17 March and 12 June 2020, 167 health care and health support workers were infected with COVID-19 (11 percent of all cases). Ninety-six or 57.5 percent were likely to have been infected at work. Nine required hospitalisation as a result, two in intensive care (see endnote 94 for source). It must be noted that the cumulative infection risk of essential workers through 2020 and 2021 was considerably less than in other countries, and most essential workers were younger and less vulnerable to serious illness from COVID-19. However, they were still at risk of becoming infected themselves and also of ‘taking it home’ to vulnerable family and friends. In another pandemic, the risks to essential workers may be greater.

ix Senior Police officers told us that they heard ‘stories of our people living in tents at home because families didn’t want them to come into the home or stripping off to be hosed down to be entering the house, or relationships strained because exposing greater family potentially to infection’. A union member in an essential workforce told us that: ‘I did not see my family for months as I isolated myself so they would not get COVID – we put much effort into following the rules and then saw people not following rules and increasing risks’. See also endnote 94.

x Mental health impacts are discussed in more detail in Chapter 6.

xi The Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) is an OECD initiative that compares the standardised reading, maths and science scores of approximately half a million 15-year-old students selected at random from 81 participating countries, including Aotearoa New Zealand. It is undertaken every two years.

xii ERO identifies Pacific students as a group whose learning has been particularly impacted. A follow-up report on the pandemic’s specific impacts for Pacific learners noted their achievement declined in 2021 after an increase in 2020. The fall was more pronounced for Pacific learners than the general population and Pacific learners continue to sit below the general population for achievement at NCEA levels 1, 2 and 3 and for university entrance. See: Learning in a Covid-19 World: The impact of Covid-19 on Pacific Learners.