A.3 All-of-government systems and structures

At the start of 2020, responsibility for preparing for and responding to national emergencies lay with multiple systems, entities, functions and teams across central and local government. They were:

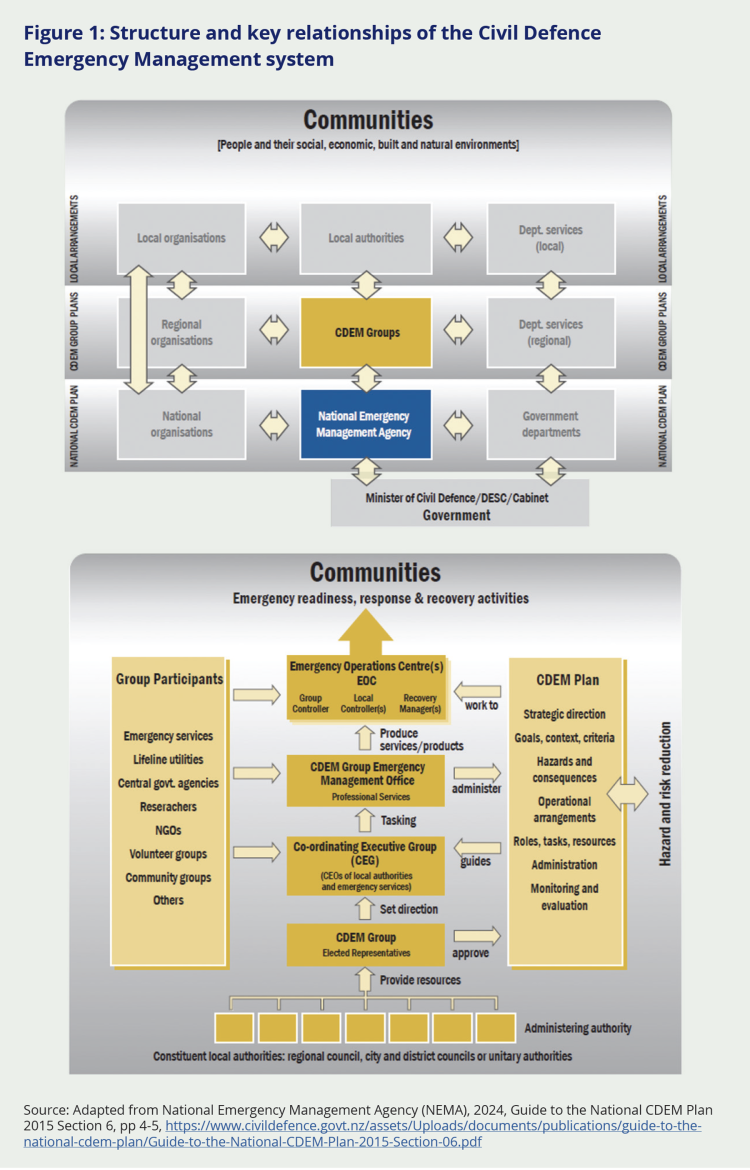

3.1 The civil defence emergency management system

This system sets the framework to reduce risk, prepare for, respond to and recover from national and local emergencies and is part of the wider national security system (see section 3.2). It is led by the National Emergency Management Agency (NEMA), whose role is to support the Director of Civil Defence Emergency Management to carry out the functions and duties required of them under the Civil Defence Emergency Management Act 2002. NEMA oversees the ‘4 Rs’ of emergency management – reduction, readiness, response and recovery. It is an autonomous agency hosted by the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet.

While NEMA provides leadership and stewardship, the civil defence emergency management system is a devolved accountability model. There are 16 regionally-based Civil Defence Emergency Management Groups (collectives of local and/or unitary authorities within each region with membership made up of elected officials) that provide the most visible face of the system on-the-ground. Because they are usually required to swing into action quickly, and sometimes to take life-saving measures, they operate with a degree of autonomy; for example, they can appoint someone to declare a state of emergency or a mayor can. All parts of the system use a common operating framework (Coordinated Incident Management System or CIMS) to ensure they work consistently and effectively. Civil Defence Emergency Management Groups are supported and advised by a group of senior representatives from the local authorities, emergency services and health and disability service providers in their region.xviii

Figure 1: Structure and key relationships of the Civil Defence Emergency Management system

Source: Adapted from National Emergency Management Agency (NEMA), 2024, Guide to the National CDEM Plan 2015 Section 6, pp 4-5, https://www.civildefence.govt.nz/assets/Uploads/documents/publications/guide-to-the-national-cdem-plan/Guide-to-the-National-CDEM-Plan-2015-Section-06.pdf

Even though the civil defence emergency management system was set up to address ‘all-hazards, all-risks’, its experience has been largely with natural hazard events. More than 100 state of emergency declarations have been made since 2002, and the COVID-19 pandemic declaration is the only one to have been triggered by something other than a natural hazard or fire.33

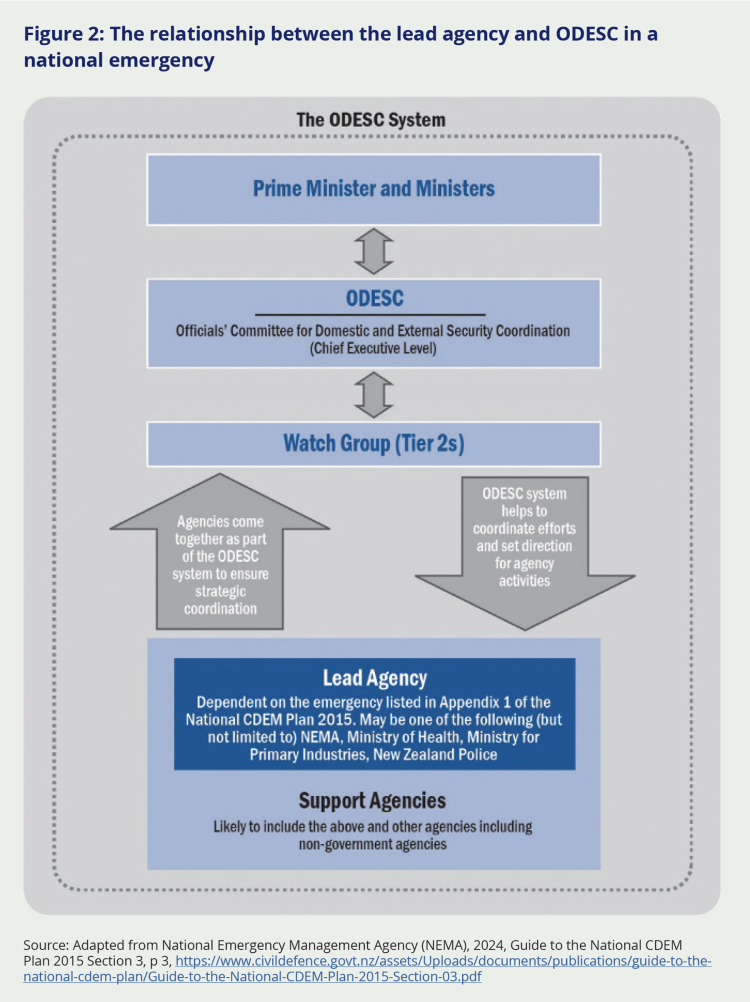

3.2 The national security system and its supporting structures34

The national security system deals with all risks to national security, ranging from terrorism incidents to natural hazards and public health emergencies, and has a strategic and coordinating role across government. It is led by the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet.

When events occur that require strategic all-of-government coordination in line with pre-identified triggers, the ODESC system is activated alongside the emergency management system. This was the case with the COVID-19 pandemic.

The national security system has both a response role and a strategic/governance role. The arrangements for the first are well-established, remaining essentially unchanged since 1987. When the national security system is in response mode, the key players are:

- The Officials Committee for Domestic and External Security Coordination (ODESC) chaired by the Chief Executive of the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, the committee comprises chief executives from a range of relevant agencies who work together as a collective. ODESC’s role is to provide strategic direction and coordination for the all-of-government response to an emergency or security event, and to advise the Prime Minister, Cabinet, and Cabinet’s External Relations and Security Committeexix (when activated). It ensures the lead agency has the resources and capabilities it needs and gives advice on risks outside the lead agency’s control.35 ODESC meets only during an emerging or actual emergency or event.

- Red Teams, which can be established by the chair of ODESC to carry out ‘semi-independent real-time review[s]’ of specific response activities. These short, focused reviews are intended to ‘assure ODESC that the full range of actions is being considered for a response’ and to identify‘undetected vulnerabilit[ies]’.36

- Watch Groups which are formed to monitor potential, developing or actual crises. They usually comprise officials from relevant agencies with sufficient seniority to commit resources and agree actions on behalf of their organisations. Watch Groups are responsible for ensuring ongoing high-level coordination between agencies, and for the provision of assessments and advice to ODESC.37

- The lead agency (see section 3.3).

The national security system’s strategic/governance role is concerned with risk management and building national resilience across government, comprising:

- The Security and Intelligence Board (now the National Security Board), another grouping of agency chief executives which focuses on external threats to national security and intelligence issues.

- The Hazard Risk Board (now the National Hazards Board), chaired by the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet’s Deputy Chief Executive for Security and Intelligence. It includes the Department’s Chief Executive and the Chief Executives of New Zealand Police, the Ministry of Health, the Ministry for Primary Industries, the Ministry of Transport, the New Zealand Defence Force, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade, the New Zealand Fire Service, and the Ministry of Civil Defence and Emergency Management. The National Security System Handbook (2016) described the Board’s purpose as building ‘a high performing and resilient National Security System able to manage civil contingencies and hazard risks through appropriate governance, alignment, and prioritisation of investment, policy and activity’.38

- The Strategic Risk and Resilience Panel, an independent group whose members have expertise in many areas and are drawn from both the public and private sectors. Its role is ‘to provide a rigorous and systematic approach to anticipating and mitigating strategic national security risks’.39

3.3 The lead agency model

This is a common international model whose use in Aotearoa New Zealand is set out in the National Civil Defence Emergency Management Plan 2015 and accompanying guide. Under this model, the lead agency’s role in emergencies at the national level is to:40

- Monitor and assess the situation.

- Plan for and coordinate the national response.

- Report to ODESC and provide policy advice.

- Coordinate the dissemination of public information.

Agencies that have lead agency responsibilities are required to develop and maintain the necessary capability and capacity to undertake the role.41

As noted earlier, the National Civil Defence Emergency Management Plan lists the agencies that are ‘mandated through legislation or expertise’ to carry out the role of lead agency, according to the hazard involved. NEMA is the lead agency for emergencies involving meteorological or geological hazards and infrastructure failures. The Ministry of Health is the lead agency for emergencies arising from infectious human diseases under the National Civil Defence Emergency Management Plan.42

Although the lead agency has the ‘primary mandate’ for managing the response, it does not work alone. NEMA has specific responsibilities, and other government and non-government agencies may be expected to provide support. The lead agency reports to ODESC and provides policy advice.

Figure 2: The relationship between the lead agency and ODESC in a national emergency

Source: Adapted from National Emergency Management Agency (NEMA), 2024, Guide to the National CDEM Plan 2015 Section 3, p 3, https://www.civildefence.govt.nz/assets/Uploads/documents/publications/guide-to-the-national-cdem-plan/Guide-to-the-National-CDEM-Plan-2015-Section-03.pdf

3.4 The risk management system

3.4.1 National Risk Register

Government’s primary tool for helping inform the management of nationally significant hazards and risks is the National Risk Register, which is led and maintained by the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet.43 The register lists the most significant risks that Aotearoa New Zealand faces at any given time, identified on the basis of evidence and expert advice.

In 2020, the register listed both ‘threat-type’ risks (such as terrorism and cyber security) and a larger group of ‘hazard-type’ risks, including the risk of a pandemic. All risks on the register were overseen by either the Security and Intelligence Board (threats) or the Hazard Risk Board: the latter oversaw 30 hazard risks, including pandemics. Individual agencies were expected to support the work of these two governance boards, alongside managing specific risks in their areas of operation.

3.4.2 Emergency Exercises

The Hazard Risk Board (now the National Hazards Board) is responsible for oversight of the National Exercise Programme – this includes monitoring the results of mock ‘system readiness’ exercises aimed at building capability across government by bringing agencies together to respond to various simulated emergency scenarios (hazard and threat-based). Three all-of-government national pandemic exercises had taken place before 2020; Exercise Virex in 2002, Exercise Cruickshank in 2006-2007 and Exercise Pomare in 2017-2018. All were based on influenza infection scenarios. Such exercises provided opportunities to build public sector capability and test emergency plans for a national pandemic. Exercise Pomare had a specific goal of familiarising senior leaders and managers with long-term emergencies, and was also intended to inform ongoing work on the Influenza Pandemic Plan.44 The Hazard Risk Board was to consider the outcomes and any lessons to be learned from such exercises.

3.4.3 National Security Intelligence Priorities

First developed in 2012 and subsequently updated on several occasions, this list of Cabinet-approved priorities provided another national risk management mechanism. It was intended to help agencies involved in the national security system focus their risk-monitoring and intelligence-gathering efforts; however, it was not designed to guide day-to-day operational or longer-term strategic decisions. At the start of 2020, the National Security Intelligence Priorities comprised 16 equally-weighted priorities. One was ‘threats to biosecurity and human health’, including pandemics.