5.6 Our assessment of the outcomes and impacts Tā mātau arotake i ngā putanga me ngā panga

5.6.1 Aotearoa New Zealand’s health system was not overwhelmed, and most people – especially vulnerable groups – were well protected from COVID-19

It is well established that pandemics (and other kinds of crises and disasters) will have the greatest negative impacts on the parts of the population who are already facing systemic inequities and underlying disadvantages. This is true of both the direct impacts of the pandemic virus or pathogen itself, and of the indirect economic, social and health impacts that can result from a pandemic. Proactive steps can – and should – be taken to mitigate this likely effect as much as possible.

When considering the health system response to the COVID-19 pandemic in Aotearoa New Zealand then, we have been mindful of both historical and international examples. The 1918 influenza pandemic and its devastating impact on indigenous peoples here and around the world, has been a salient consideration (as it was for the Government and for many Māori during the pandemic response). So too have examples of health systems overwhelmed by COVID-19 in Italy, the United Kingdom, India, the United States and elsewhere.

“It was hard. Really hard. But having tens of thousands of whānau and friends die would have been harder.”

Keeping these ‘counterfactual’ examples in mind has helped us to interpret the evidence we saw and heard about the wider health impacts of New Zealand’s COVID-19 response. It is of course impossible to know exactly what might have happened under alternative circumstances and if different decisions had been made (although Appendix B provides some scenarios to consider).

We also note that work on major health care reforms was underway while Aotearoa New Zealand was dealing with the COVID-19 pandemic. They were introduced on 1 July 2022.xx

There can be no doubt that New Zealand’s COVID-19 response – particularly the success of the elimination strategy, and the time this bought to achieve high levels of vaccination coverage – was highly effective at protecting public health, preventing the health system from being overwhelmed, and minimising unequal health impacts for disadvantaged or vulnerable populations, including Māori. Many public submitters to our Inquiry expressed gratitude for how the COVID-19 response protected public health, and the health system.

“I was so very proud of how our government & public health initially handled the pandemic – protecting the health of the people of New Zealand was at the centre.”

“...the way the Government and government departments and officials handled the pandemic and responded with public health measures absolutely saved lives. It was hard. Really hard. But having tens of thousands of whānau and friends die would have been harder.”

5.6.1.1 Low infection, hospitalisation and death rates

The public health and infection control measures activated during the pandemic were deployed in service of the overarching elimination strategy that governed New Zealand’s COVID-19 response from late March 2020 until late 2021. This strategy, and the measures deployed in support of it, were highly successful in preventing the health system from being overwhelmed and in protecting the health of people living in Aotearoa New Zealand.

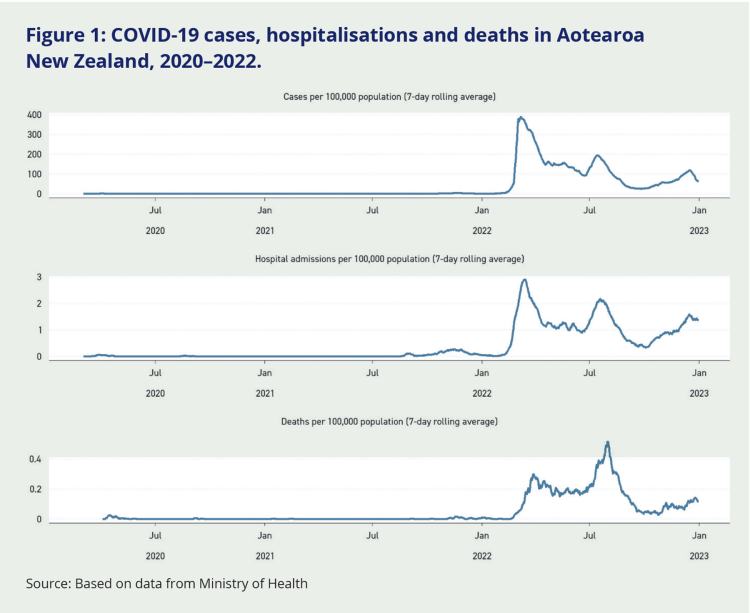

COVID-19 was largely absent from the country until early 2022. While the lockdowns of early 2020 and late 2021 were highly disruptive, they also ensured that case numbers were very low. Following the initial success of the first national lockdown in 2020, community transmission was successfully re-eliminated in August of that year. Not until the arrival of the Delta variant in August 2021 did it became re-established – and even then, case numbers, hospitalisations, and deaths in this period were very low – barely visible compared with what came later in 2022. As Figure 1 shows, the first two significant ‘waves’ of COVID-19 infections in Aotearoa New Zealand only occurred in 2022, the first in March/April and the second in July/August.

Figure 1: COVID-19 cases, hospitalisations and deaths in Aotearoa New Zealand, 2020–2022.

Source: Based on data from Ministry of Health

When COVID-19 transmission did eventually become widespread in Aotearoa New Zealand, the population had high levels of immunity from vaccination. Not only did this protect many people from developing severe illness when infected with COVID-19, it also meant that New Zealand’s health system was never overwhelmed.

Aotearoa New Zealand’s hospitalisations and deaths from COVID-19 have been much lower than those seen in countries where the first waves of infection occurred before vaccination.

New Zealand’s COVID-19 hospitalisations peaked in March 2022 at just under three admissions per 100,000 population per day (as seen in Figure 1). While there were challenging moments for New Zealand’s hospitals, particularly when COVID-19 waves coincided with high rates of other respiratory infections like influenza and RSV, the system was largely able to absorb these peaks. By comparison, the United States and the United Kingdom experienced peak hospitalisation rates of more than 6 admissions per 100,000 population per day, twice the peak in Aotearoa New Zealand, and their hospital systems struggled accordingly.89

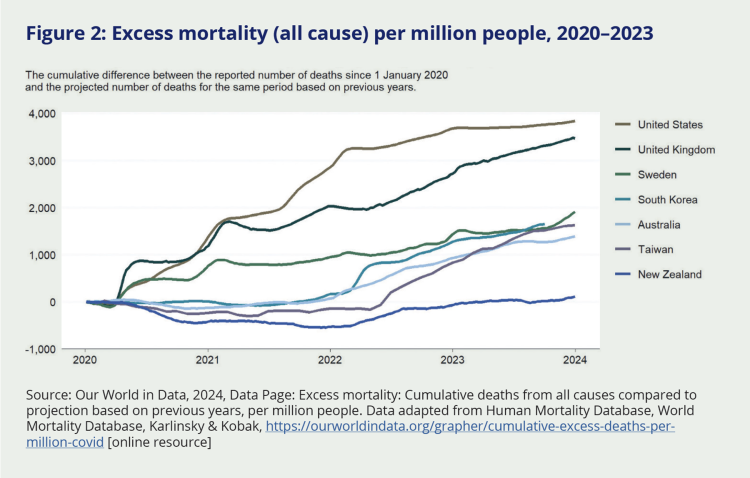

Aotearoa New Zealand experienced fewer COVID-19 deaths per head of population than almost any other OECD country,xxi as reflected in its exceptionally low excess mortality. (The measure of ‘excess mortality’ is commonly used to compare the impact of COVID-19 on death rates in different countries.)xxii In fact, New Zealand had ‘negative’ excess mortality (i.e. fewer deaths than would have been expected based on previous years) from early 2020 until early 2023 (see Figure 2), a fact attributed to the positive impact of lockdowns and other infection control and public health measures on the transmission of other infectious diseases.

Figure 2: Excess mortality (all cause) per million people, 2020–2023

Source: Our World in Data, 2024, Data Page: Excess mortality: Cumulative deaths from all causes compared to projection based on previous years, per million people. Data adapted from Human Mortality Database, World Mortality Database, Karlinsky & Kobak, https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/cumulative-excess-deaths-per-million-covid [online resource]

5.6.1.2 Effective protection of vulnerable populations

The need to protect vulnerable groups was an important consideration for decision-makers in the decision to pursue an elimination strategy in the early stages of New Zealand’s COVID-19 response. The experience of the 1918 influenza pandemic and the Crown’s responsibilities to Māori under te Tiriti o Waitangi were prominent considerations in the minds of senior officials and decision-makers, as were the many pre-existing social determinants of health that disproportionately disadvantaged particular ethnic groups, household types, income levels and disabled people.

One senior Ministry leader told us that ‘equity underpinned what we were doing from the get-go, even if it wasn’t explicitly stated’. According to another, ‘We were conscious of the toll of the 1918 pandemic on Māori and wanted to avoid a similar situation. We were also conscious of the need to protect older people, especially those in aged care, Pacific people, people with disabilities, and people in mental health institutions’.

Our assessment of the evidence overwhelmingly supports the conclusion that the elimination strategy (and the public health and infection control measures that enabled it) offered the best protection for the population as a whole, and greater protection for Māori, Pacific people, older people and medically vulnerable people than would have been possible with either a suppression or mitigation strategy.

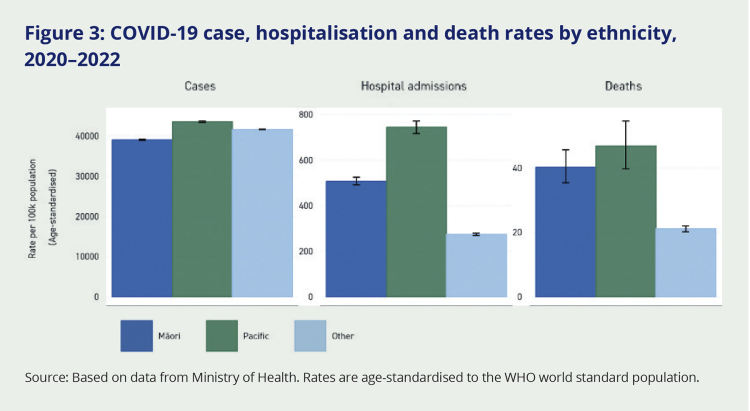

The story is complicated, however, because these groups did experience more severe impacts from COVID-19 than the general population. Severe illness from COVID-19 was more common in less privileged ethnic and socioeconomic groups, who were more likely to be hospitalised and to die from their illness.

Figure 3: COVID-19 case, hospitalisation and death rates by ethnicity, 2020–2022

Source: Based on data from Ministry of Health. Rates are age-standardised to the WHO world standard population.

In Figure 3, the risk of catching COVID-19 was fairly even across Māori, Pacific and other ethnic groups (allowing for some slight differences in case detection rates). However, adjusted for age, Pacific peoples were more than twice as likely to be hospitalised and to die from COVID-19 compared with non-Māori non-Pacific peoples (predominantly Pākehā or European New Zealanders).

Māori were nearly twice as likely to become severely unwell with COVID-19.xxiii

In relation to deprivation, people living in the most deprived neighbourhoods were twice as likely to be hospitalised and to die from COVID-19 than those living in the richest neighbourhoods (see Appendix B for more details). Such inequalities are in part a function of different risk factors – such as higher rates of certain diseases, or higher rates of smoking – that often occur together in low-income groups.

While such inequalities are certainly concerning, they are smaller than those seen in previous pandemics.90 Historical examples including influenza pandemics in 1918, 1957 and 2009xxiv suggest that – in the absence of an effective elimination strategy and vaccine rollout – the absolute gap in COVID-19 death rates between Māori/Pacific people and people with European ethnicity would have been even higher.

While these conclusions about Aotearoa New Zealand are not directly comparable with other countries (because of New Zealand’s unique population distribution and ethnic make-up), they are consistent with international findings showing COVID-19 was more likely to cause severe infection in people with lower incomes, education and/or poorer housing conditions.91

Although the 2021 Delta outbreak had a disproportionate impact on Māori and Pacific communities, most New Zealanders (including Māori and Pacific people) were not exposed to COVID-19 until the less virulent Omicron variant was circulating. By this time, most had been vaccinated. Collectively, these factors – propelled by the success of the elimination strategy – reduced the potential health impacts of COVID-19 for everyone, including vulnerable groups.

Another success factor that helped prevent even greater illness and deaths among at-risk groups was the mobilisation of these groups themselves, including the rapid response by community health providers, iwi and Māori organisations, and ethnic communities (see section 5.5.3.1). Some public submissions praised Māori-led pastoral care and outreach to isolated community members, as well as similar efforts by Pacific communities: according to one submitter, ‘Māori and Pacific communities did the right thing by going door to door to people who needed more understanding and assistance of the effects of COVID’.

Finally, it is worth addressing the extreme variation in COVID-19 death rates between different age groups. This was a prominent feature of the pandemic, but is sometimes missed (or treated as too obvious to mention). A global analysis of COVID-19 death rates has found that a 90-year-old person infected with the virus was approximately 10,000 times more likely to die from it than a 7-year-old.92 In Aotearoa New Zealand, the vast majority of COVID-19 deaths and hospitalisations also occurred among older people, but many more such deaths would have likely occurred had the elimination strategy not been so effective.

5.6.1.3 People staying in hospitals and aged residential care settings were well protected, but there were social costs

Given the greater susceptibility of older people and people who were already unwell or immunocompromised, it was appropriate that hospitals, aged residential care facilities, and other residential care settings should have strong infection control practices in place during the pandemic. Such restrictions were also important to protect staff and prevent these kinds of facilities from becoming sites of ‘super-spreader’ events or major vectors of transmission back out into the community. The importance of these measures was reinforced by five early COVID-19 clusters in aged residential care facilities, one of which resulted in some of the first deaths from COVID-19 in Aotearoa New Zealand.93

Aside from these early clusters, aged care facilities were highly effective in protecting their residents from COVID-19 and New Zealand saw significantly fewer aged care deaths during the pandemic, compared to other countries. Across the two years from March 2020 until March 2022, mortality rates among aged residential care residents were essentially the same as for the two years prior. In 2020 and 2021, very few deaths with COVID-19 were recorded among aged residential care residents, and where they were recorded, they accounted for approximately one percent of monthly deaths. In contrast, by January 2021, it was estimated that 75 percent of all COVID-19 deaths in Australia had occurred among care homexxv 94 residents.95

New Zealand’s lower death rates in aged care facilities have been attributed to the strict protective measures that were taken in these facilities (particularly strict visiting protocols) and – from mid-2021 onwards – high vaccination rates among residents. Overall, the aged care sector galvanised effectively to advocate for the needs and interests of its residents, and was proactive in generating nationally consistent and fit-for-purpose guidelines and advice for care homes.96 Beyond the initial clusters, the overall absence of severe outbreaks in New Zealand’s aged residential care facilities was a major success story of the pandemic. However, this was not without harm for residents who lived through long periods of limited contact with their loved ones.

New Zealand saw significantly fewer COVID-19 deaths among care home residents than other countries.

Negative impacts of strict visitor limits and reduced social contact

Prolonged social isolation and visitor restrictions are known to have negative physical and emotional impacts on residents of aged care facilities, as well as their families/whānau, and staff.97 This may be especially true for people with dementia, to whom it could be challenging to convey the purpose and scope of the restrictions. Other restrictions also took a toll, such as the inability of residents to gather for communal meals, and the increased time involved in staff having to attend to each resident separately. This is illustrated in the following excerpt from a public submitter:

“I work in a resthome. We have had 2 outbreaks and 2 resulting deaths. […] Locking the doors to family/friends was awful – I understand the need when we were trying to eliminate Covid from the country, but it seemed inhumane later. Residents had meals in their rooms on disposable plates etc and it was very obvious that the amount they ate was considerably less than when in the dining room. Our dementia patients in particular need prompts of seeing others eating to do the same. Keeping food hot was impossible. The time taken to do tasks increased hugely. Most staff did their absolute best but we felt like we were winging it at times.”

The Health and Disability Commissioner received many complaints in 2020 about the impact of the pandemic on the health system, including visitor restrictions.98 When we met with the present Commissioner, she noted that visitor restrictions are a very strong public health measure, and expressed the view that a more compassionate, risk-based approach could have been applied, particularly later in the pandemic.

Even once vaccination rates were high and Aotearoa New Zealand had transitioned to the minimisation and protection strategy, some aged residential care providers were slow to lower restrictions, despite official health advice that the risks to residents were now lower. In advice to ministers at this time, health officials expressed concern that this constituted an unfair restriction on the rights of aged care residents.

Prolonged social isolation and visitor restrictions are known to have negative physical and emotional impacts on residents of aged care facilities.

Similarly, the inability to visit loved ones in hospital – or be visited – was a source of considerable hurt for many people during the pandemic. We received public submissions that gave moving accounts from affected patients and family members alike:

“Being rushed to hospital because I had a racing heart […] My husband was not allowed to come with me. I was so scared that I would die without my husband of 43 yrs plus seeing my sons and grandkids.”

“In September 2021 my sister was diagnosed with a return of her breast cancer which was now terminal. As she lived in Auckland and I didn’t, it was extremely hard to take the fact that I could not be of any assistance to her for her cancer treatment appointments etc. as the border was closed. My sister died the day the Auckland lockdown was ending at midnight.”

A qualitative study of visitor restrictions in cases where people died alone found evidence of deep distress, loss of dignity, and long-term harm. Family members in the study felt as though they had abandoned their dying family member, despite the circumstances beyond their control. Their associated grief was exacerbated by other losses during COVID-19. Both clinicians and family members involved in the study questioned the level of compassion evident in the health system during this time.99

Senior DHB leaders told us in direct engagements that strict visitor policies were one of the hardest public health protection measures for them to manage. Some told us that these restrictions affected the provision of care to patients, relationships with family and whānau, and expressed a view that they were too restrictive, especially when people were dying and unable to have whānau present. We heard the view that while well-intended, the personal consequences – and, in some cases, trauma – caused by such restrictions will be enduring for many families. This view was also evident in the public submissions we received.

“My birth experience was lonely. I wanted my mother there but was only allowed one person so I had my partner there who was distraught at being back at the same hospital his father had died at a few months before. It was a lonely, isolating experience to feel so on your own during birth.”

5.6.2 COVID-19 revealed pressure points in the health system that – if not addressed – may present risks in a future pandemic.

The overall story of Aotearoa New Zealand’s health system response to COVID-19 is a complicated one. It is simultaneously a story of remarkable success at protecting public health (via the elimination strategy) and a cautionary tale of potentially disastrous pandemic impacts (on an already strained system) that were narrowly averted.

These are two sides of the same coin: had the elimination strategy not successfully prevented the health system from being overwhelmed, the vulnerabilities revealed and exacerbated by the pandemic might have had much greater consequences. To borrow an eloquent phrase from the Health Quality and Safety Commission, the pandemic added to ‘a rising tide’ of need in New Zealand’s health services, rather than causing a ‘sudden tsunami’ as occurred in many other countries.100

The dual successes and challenges in the health system response to COVID-19 provide ample opportunities to learn from what occurred (and from what didn’t) and to apply these lessons in preparing for future pandemics. We return to these opportunities in the ‘Looking Forward’ parts of our report.

Some of the pressure points that COVID-19 revealed in New Zealand’s health system – including workforce issues, ageing infrastructure, pandemic readiness, regional inconsistencies and underlying health inequities – are assessed below. They presented some significant risks; while not all of them were realised during the COVID-19 pandemic, Aotearoa New Zealand may not be so fortunate next time.

5.6.2.1 Public health capacity to respond to a pandemic

Testing capacity

Individual diagnostic testing is a critical tool in any pandemic response and underpins the effectiveness of many other response measures. For example, being able to quickly and accurately determine whether or not someone has a virus means that unnecessary quarantine of non-infected individuals can be avoided. Aotearoa New Zealand’s capacity to carry out diagnostic testing was limited during the COVID-19 pandemic in two ways: by the limited laboratory capacity to carry out PCR tests, and by the slowness to approve alternative testing options.

PCR tests, which were the primary method of COVID-19 testing in Aotearoa New Zealand for much of the pandemic, must be processed in a laboratory. Most diagnostic laboratories in New Zealand are privately owned by a small number of companies. Many are embedded in hospitals and only carry out work for the public health system; others deliver a range of private laboratory services. While this laboratory network stepped up in the face of COVID-19, the pandemic severely strained New Zealand’s diagnostic testing capacity.

In early 2020, laboratories that could deliver PCR tests organised themselves into a voluntary National Laboratory Network Group, which worked directly with the Ministry of Health.101 Despite their competitive commercial relationship, laboratories collaborated to ensure samples got processed, for example by sending samples to other labs that had capacity.

As the pandemic wore on, the vulnerabilities in New Zealand’s diagnostic testing system became more apparent. An article published in September 2020 provides some early examples of the issues this caused:

“Each individual lab was responsible for its own supply chain. Because global supplies of the components needed for COVID-19 tests were severely constrained, the every-lab-for-itself approach resulted in suboptimal results for the country as a whole.”102

While many laboratory staff willingly stepped up and worked long hours in challenging conditions, the negative ongoing impacts on the testing workforce have been evident in subsequent strike action, with workers saying they are burnt out from operating under poor conditions during the pandemic.103

A review carried out in May 2022 found that the Ministry had not communicated anticipated increases in demand to laboratories, which might have helped ensure sufficient testing capacity throughout the pandemic response.104 The review also noted a lack of forward planning about how to build the capacity that might be needed in future, since relying solely on PCR testing was only practical when COVID-19 infection was uncommon and tests could therefore be pooled (see section 5.3.2.2). The authors concluded that the Government may not have fully understood the capacity constraints mounting in the laboratory sector in late 2021. Their review said the significance of positivity rates as an ‘advance indicator’ of PCR capacity was not properly communicated to decision-makers – nor used meaningfully in modelling – despite messaging from laboratories. This meant concerns about rising positivity rates and the effects on testing capacity did not inform decisions about when the shift to rapid antigen tests (RATs) would be needed.105

This contributed to the laboratory testing system becoming overwhelmed in early 2022 when COVID-19 began to circulate widely.

The issue of capacity constraints in laboratories was connected with the lack of alternative testing options. As we noted in section 3.2, the Government did not approve the use or importation of RAT tests – which are self-administered and give a result within 15 minutes – until late 2021. The lack of diagnostic testing options outside of PCR tests caused frustrations for many, including business representatives who told us that testing options which returned rapid results should have been available sooner.

Some public submissions described the challenges of accessing PCR tests faced by disabled people or those without access to a vehicle (for drive-through PCR tests).

“My Aunt sat in her car with 2 masks on for five hours waiting to get a covid test. There’s no way I could have gotten my ADHD Autistic son to wait that long, it would be cruel.”

“When I had symptoms & needed to be tested I made repeated enquiries about arrangements for those of us unable to drive […] My phone call resulted in the suggestion that I hire a taxi. Somehow I don’t think a taxi driver would want to wait in a queue with me for hours coughing.”

“Being able to access testing, and later test kits, for free was, I believe, absolutely essential. We live in a low socio-economic area and I’m not sure that families here were really able to afford multiple test kits, not with the cost of living crisis we’re currently in.”

Once the decision to transition to RAT testing was finally made in late 2021, the rollout of tests was hampered by lack of supply. As imports of RAT tests had been banned for most of 2020 and 2021,106 stockpiles had not built up in anticipation of a change in testing strategy.107 Until adequate supplies could be secured, the implementation of other public health measures – such as the use of testing to determine whether people were safe to go to work – was hampered.

Once RAT tests were permitted and freely available, it was much easier for people to take up voluntary testing.

More effective and efficient COVID-19 testing would have been achieved if there had been more pragmatic use of alternatives to PCR tests (alongside PCR testing, when higher accuracy was needed) and earlier planning for the rollout of RAT tests. In planning for a scenario with a highly vaccinated population and less reliance on stringent public health measures, the benefits of RAT testing should have been seen in advance as outweighing their lower accuracy, and planned for by ordering and stockpiling tests in advance of when they needed to be deployed. Approving and acquiring RAT tests earlier may also have mitigated some of the issues with laboratory capacity for PCR testing, ameliorated frustrations experienced by businesses and individuals, and supported more effective implementation of other public health policies.

Issues with COVID-19 testing reinforce the challenges created by a lack of forward strategic planning and an overly narrow approach to risk assessment and management (discussed in Chapter 2).

Under an elimination strategy, it was certainly beneficial to make use of high accuracy PCR tests for suspected cases, close contacts and people working at the border. However, for employers trying to get their businesses back up and running after lockdowns, earlier access to quick, self-administered options like RAT tests would have been very useful. Earlier access to RAT tests would also have assisted with the transition from elimination to the ‘minimisation and protection’ phase of the response, when priority shifted from very high accuracy to higher availability of COVID-19 tests. As it was, the pivot to RAT tests was hampered by supply chain limitations and global shortages of key products, pointing to additional areas in which future pandemic preparedness could be strengthened.

Contact-tracing capacity

The delivery of effective contact tracing during the COVID-19 pandemic was a success, but also a vulnerability in the early stages of the pandemic.

Contact tracing is a vital tool in stamping out or slowing down transmission during a pandemic.

Contact-tracing capacity was very limited at the start of the pandemic,108 and it took time to be scaled-up to an effective and integrated service. Once it was in place, central coordination provided for national consistency, but there were concerns that the system wasn’t sufficiently flexible or responsive to the needs of vulnerable and high-risk people. We heard that some groups, particularly Māori and Pacific people, were reluctant to engage with ‘mainstream’ services and were more comfortable discussing who they may have been in contact with when the contact tracer was someone from their own community. Given the critical importance of rapid contact tracing for the effective isolation of positive cases, these issues should be addressed to be better prepared in the future.

The platform developed by the Ministry of Health’s digital team in response to COVID-19, the National Contact Tracing Solution, was key to making national contact tracing operate smoothly. Health staff emphasised that such fundamental technology should be maintained so it can be quickly deployed in a future pandemic. We are not aware of a formal evaluation of the quality of contact tracing in Aotearoa New Zealand as it evolved in 2020, driven by the National Contact Tracing Solution. In our engagements we heard that while there were some initial challenges with the IT platform, overall it worked well, and that local efforts to scale-up contact tracing, including bringing in new contact tracers under the supervision of experienced staff, paid off.

The COVID Tracer App was a ubiquitous part of many New Zealanders’ experience of the pandemic. We heard through public submissions that many people found the app easy to use and a useful reminder to be conscious of COVID-19 precautions.

“The use of the Covid app was fantastic and provided a degree of comfort knowing your potential exposure would be notified to you.”

However, the app may not have been as useful for contact tracing as was envisaged (see also Chapter 8). Recent research from the University of Otago has concluded:

“The QR-code-based function of the NZCTA likely made a negligible impact on the COVID-19 response in New Zealand in relation to isolating potential close contacts of cases but likely was effective at identifying and notifying casual contacts.”109

Contact tracing, along with accurate testing and effective isolation and/or treatment options, is a vital tool in any pandemic response. The fact that there was no national contact-tracing capability before COVID-19 exposed this vulnerability in our public health system. In the event, the Ministry of Health was able to rapidly establish the National Close Contact Service and evolve this service as the pandemic progressed. But with better preparation, Aotearoa New Zealand could be more confident that such a system can be quickly scaled-up, and be effective, in another pandemic.

5.6.2.2 Hospital and system capacity to manage an infectious outbreak

Intensive care capacity

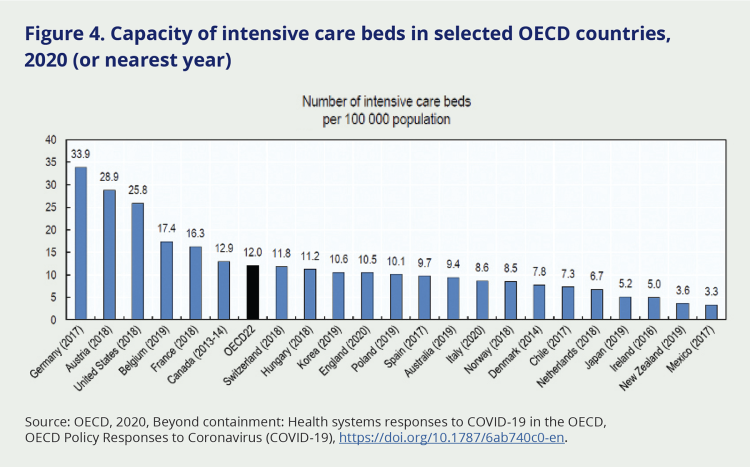

As noted in section 5.4.1.2, Aotearoa New Zealand had limited intensive care capacity going into the pandemic. Evidence available to our Inquiry suggests this was not substantially increased during the first two years of the COVID-19 response, although in early 2022, $100 million capital funding and $544 million operational funding was agreed for enhanced ICU capacity.

Figure 4. Capacity of intensive care beds in selected OECD countries, 2020 (or nearest year)

Source: OECD, 2020, Beyond containment: Health systems responses to COVID-19 in the OECD, OECD Policy Responses to Coronavirus (COVID-19), https://doi.org/10.1787/6ab740c0-en.

Health system capacity includes staff, supplies and space.110 In the case of capacity to manage ventilated patients, the availability of trained staff and suitable hospital accommodation is just as critical as the availability of ventilators. While Aotearoa New Zealand reportedly acquired additional supplies of ventilators in the first year of the pandemic,111 and non-ICU nurses received some training in preparation for a surge in demand,112 critical care nurses expressed doubt that there had been a surge in staff training or numbers.113

Because of the effectiveness of the elimination strategy and subsequent vaccine rollout, Aotearoa New Zealand never experienced the dramatic peaks in illness that overwhelmed hospitals in many other countries. We were therefore fortunate that our capacity to care for patients needing ventilation was never tested, and the absence of meaningful expansion in 2020 and 2021 did not limit our pandemic response.

Workforce issues

The health system was experiencing many long-standing and destabilising workforce issues entering the pandemic, which complicated both the health system response to COVID-19 and the continuous delivery of ‘business as usual’ healthcare. The Inquiry heard that – pre-COVID-19 – longstanding budgetary constraints meant the public health workforce (responsible for public health activities such as contact tracing) had limited ability to develop its capacity or to build the kinds of relationships with local communities that would be needed in a pandemic response.

“I have immense pride for what our PHO contributed, but also total exhaustion. The three plus years of the pandemic has meant so much of our lives have been put on hold.”

Across the wider health workforce, key challenges included widespread staff shortages, pay equity issues within and between disciplines, high staff turnover and a high incidence of work-related stress, burnout and mental health challenges. The health workforce had not increased in line with growing population health needs, was not representative of the population being served and in parts of the sector was ageing (especially in general practice, aged care and home care). Some services (such as palliative care, home and community support and ambulance services) relied heavily on volunteers, which became a vulnerability where volunteers were older people who were being advised to stay at home.114 There were persistent staff shortages in many disciplines, including midwifery, sonography, clinical psychology, disability support and community health workers, and healthcare workers in rural areas.115 These issues were not unique to Aotearoa New Zealand, and will remain a major issue for many countries in future pandemic preparation, response and recovery.

Pandemics can have a severe physical and psychological toll on health workers. In Aotearoa New Zealand, the health system response to COVID-19 stretched the workforce and exacerbated many pre-existing issues. This was despite the elimination strategy preventing substantial waves of COVID-19 infection and hospitalisations in 2020 and 2021, which greatly reduced the pressures on the health system and staff compared to those endured in other countries.

The health workforce had to deal with multiple challenges – including long working hours, difficulty accessing PPE (particularly in primary and community care), fear of the virus or of transmitting the virus, being personally attacked for doing their job,116 having to adapt to constantly changing information and the sense that the pandemic was relentless. As well as evidence from professional bodies and colleges, we heard direct accounts from health professionals about some of these challenges in our public submissions. Some health workers who made public submissions described working during the pandemic as ‘stressful’, ‘overwhelming’, and ‘terrifying’.

“Heading into the initial stages of the pandemic was extremely worrying. We had been viewing colleagues’ experiences overseas and had no doubt we were in for the same bumpy ride... not having enough PPE, being overwhelmed with patients, and being at risk of death or morbidity from covid ourselves.”

“As a Registered Nurse it was fundamental to assist in stopping the spread fast […] Our lives changed, and for a few months we did not see our 14 year old daughter due to us not wanting to make her unwell and vice versa, especially due to my work.”

However, submissions and engagements also showed how vital and valuable health workers felt at the beginning of the pandemic. As one health professional told us:

“I love a good crisis – it was exciting to know we could make a difference. It’s what we trained for, and it was great to be able to put my knowledge to work.”

Health workforce leads from Health New Zealand |Te Whatu Ora noted that staff turnover at this time was low.

We heard from many sources – in both direct engagements and written evidence – that the health workforce is in a worse position now than before COVID-19, as a direct result of pandemic pressures.117 While this situation is not unique to Aotearoa New Zealand, it is nevertheless serious, for many reasons – not least for future pandemics. In 2023, Health New Zealand | Te Whatu Ora estimated the health system had a shortfall of around 4,800 nurses, 1,700 doctors (including general practitioners), and 1,050 midwives.118 The agency acknowledged that the workforce ‘has been under too much pressure for too long’ with the pandemic contributing to attrition in key roles (such as midwifery).119 The difficult experience of working through the pandemic – and its impact on staff retention – is highlighted in the following comments from health workers who made public submissions:

“It was all-consuming – in the PHO backrooms we lived and breathed COVID-19 non-stop, 7 days a week. It felt like we could never get away.”

“Working through the pandemic broke me, as it did many of my friends and colleagues. I am not the same person I was before the pandemic and I can see why many left the profession. We were used as workhorses but we were burnt out from being overworked before the pandemic started and it only got worse.”

5.6.2.3 Ability of the wider system to deliver ongoing non-pandemic care

From the evidence we have seen and heard, it seems many DHBs took a strongly and often overly precautionary approach to managing the risk of COVID-19 transmission in healthcare settings throughout the pandemic period.

This led to many services being paused or limited for long periods. Impacts included delayed diagnosis and treatment (including potentially serious conditions such as cancer,xxvi diabetes, stroke and heart disease), and missed opportunity for preventive care (such as childhood immunisations). Some of these impacts are still being felt.

Assessing pandemic risk

As set out in sections 5.4 and 5.5 earlier in this chapter, the main mechanism used for scaling ‘business as usual’ health service provision up or down according to the demands and risks posed by COVID-19 was the National Hospital Response Framework. At ‘red’ level, hospitals were encouraged to discharge as many patients as possible and cancel any non-emergency surgery to ensure all available capacity was available to respond to COVID-19.

We have requested, but have not received, any evidence documenting how many DHBs assessed themselves at each risk level and for how long throughout the pandemic.

However, we heard from several stakeholders that many DHBs held themselves at ‘red’ for long periods. Several – including senior officials and former ministers – expressed frustration about this. We heard it called a ‘misuse’ of the framework, while others expressed the view that too many services were cancelled, for too long. One senior DHB leader put it simply, saying ‘We didn’t need to defer as much planned care as we did’.

Some public submissions to our Inquiry illustrated the real life – and sometimes tragic – consequences of this deferred care for patients and their family members:

“I had an injury during covid that needed surgery – it took 9 months to get an MRI to diagnose the issue and 15 months to have the surgery. The delay was because the local health system didn’t have capacity to see me to organise a referral, and then hospitals lacked space for me to have surgery.”

“All non-urgent appointments were deferred. This was an urgent and necessary diagnostic appointment that should still have gone ahead. You do not mess with cardiac concerns. Nobody could have foreseen the outcome, but the one month appointment delay was simply more time than my father’s heart could take and he died in the street from a massive heart attack, four days shy of his rescheduled angiogram appointment. In my eyes, he is a Covid casualty.”

Inconsistencies also seem to have occurred in the way the national response framework was applied from region to region, at least in the early stages of the response. In April 2020, the Health and Disability Commissioner wrote to the Minister of Health expressing concern that DHBs were not applying the framework consistently. The letter noted ‘unwarranted inconsistencies’ between DHBs in how services were accepting GP referrals, which services were being withdrawn, and which planned care was being cancelled:

“The system needs to operate in a nationally consistent and coherent way. Geographical inequities in services is already an issue I see across complaints to my Office, and I am concerned that this will be exacerbated by current sector behaviour. While I recognise that each DHB will need to respond to its particular service pressures and the complexities and risk profile of its local population, it is my expectation that there is consistent nationally mandated behaviour among DHBs within each alert level.”120

The letter also pointed to a confusion between the national Alert Level System and the National Hospital Response Framework, noting that ‘elements of overlap, and a lack of clarity as to the interaction of these two frameworks, have led to some confusion in service decisions’.121

The Ministry of Health subsequently made minor modifications to the decision-making framework,122 but senior stakeholders we met with still expressed the view that non-COVID-19 care had been disrupted to a greater extent than was necessary during the pandemic response.

The pandemic is thought to have contributed to reductions in childhood immunisations and screening for some cancers – particularly for Māori, Pacific people and families living in poverty.

Impacts of deferred and delayed care

To the extent that it is possible to measure them, the pandemic’s disruptive effects on the provision of non-COVID-19 health services have been documented by the Health Quality and Safety Commission in two reports in 2022 and 2023. Among its conclusions are that the pandemic contributed to:

- Reductions in the rate of childhood immunisations, with coverage for six-month-olds falling from 80 percent in 2020 to 66 percent in 2022, and coverage for 24-month-olds falling from 91 percent to 83 percent in the same period. Māori and Pacific babies, and babies in families living in poverty, were particularly impacted.123

- Reductions in rates of screening for breast and cervical cancer, with breast screening falling from 72 percent in 2019 to 66 percent in 2020 and remaining at a lower level two years later. Pacific women experienced the greatest change, and coverage for Māori remained the lowest for any ethnicity. Cervical screening rates (which had been slowly declining since 2016) fell more sharply in 2020, and – after a slight uptick in 2021 – were by 2022 at their lowest level in 14 years, at 67 percent.124

- A ‘clogging’ of access to planned care, with the percentage of patients waiting longer than four months for their first specialist appointment increasing substantially, particularly during 2021. Meanwhile, the number of patients who, once seen, were given a commitment to treatment but did not receive it within four months more than doubled from 2021 to 2022.125

Monitoring and responding in real time

Early in the pandemic, the Ministry of Health sought funding to address healthcare backlogs occurring as a result of service disruption during the first pandemic lockdown. With $285.5 million of funding over three years, the Waiting List Initiative was intended ‘to address the COVID-19 backlog and reduce planned care waiting lists impacted by the response to COVID-19’.126 DHBs were asked to submit ‘Improvement Action Plans’ detailing how they would tackle the backlog of deferred care from the initial 2020 lockdown, which the Ministry estimated to have resulted in approximately 114,000 cancelled health appointments.127 Such plans were expected to include additional clinics and theatre sessions and possible use of private providers.

However, we have not been able to find evidence that the Ministry of Health actively monitored the impacts of the COVID-19 response on provision of non-pandemic care. The Ministry did not publish any follow-up reports on healthcare disruption after an initial one following the first COVID-19 outbreak.128 We were also unable to find evidence that the Ministry sought to change guidance to DHBs or to increase prioritisation of non-pandemic care in the COVID-19 response.xxvii

We acknowledge that health officials and DHB staff were working under extreme pressure through much of the pandemic period and may have lacked the ‘bandwidth’ to address all of the many unanticipated consequences of the COVID-19 response. It is also unclear to what extent ministers were prioritising non-COVID-19 care in their decision-making or requests for advice. At the same time, the example of cancer care (see Spotlight) illustrates that it is possible to more effectively protect delivery of non-pandemic care, particularly where there is effective real-time monitoring of service delivery and focused innovation to deliver care through alternative models.

In direct engagements, Ministry of Health officials told us about their frustrations with the lack of real-time data on health system capacity, underpinned by inadequate IT systems:

“… where we were at the start of the response, trying to get numbers out of different parts of the country, e.g. bed occupancy data, we were ringing places, there were calls to wards… a fairly painful process. But the bare bones of the information we needed was there and a whole bunch of reporting was stood up quickly, got into a rhythm that worked. Looking forward, you definitely want to do this in a more robust and reliable way.”

In 2022, the newly-formed Health New Zealand | Te Whatu Ora acknowledged that ‘several thousand people are waiting more than 12 months for access to an array of services, despite a maximal waiting time requirement of four months; and many thousands more are waiting between four and 12 months.’129 The agency launched a Planned Care Taskforce aimed at reducing waiting times and eliminating ‘the growing inequity of access affecting Māori and Pacific on planned care waiting lists’.130 The Taskforce Plan described the pandemic as having had ‘a profound adverse effect’ on waiting lists, but noted that waiting times had been increasing even before this occurred.

The intent of the national response framework (and associated guidance) was to balance the need for ‘usual’ healthcare with the need to protect capacity for responding to surges in COVID-19. Implicit in this is an understanding that the extent to which other services were deferred or cancelled would be adjusted in real time in response to the changing level of COVID-19 risk to the health system.

In this respect, the evidence we have heard and reviewed suggests the framework did not work as well as intended. At times when community transmission of COVID-19 was occurring and growing – in early 2020 heading into the first national lockdown, for example, or during the Delta outbreak in late 2021 – it is understandable that many non-COVID-19-related procedures would be deferred or cancelled. However, by mid-2020, the elimination strategy had succeeded and there followed a long period with no community transmission. From our understanding of the evidence we have reviewed and the stakeholders we have spoken to, it seems that during this period, more non-COVID-19-related care could have resumed – and sooner – than it did.

Innovating to ensure continuity

Despite these challenges, many parts of the health system worked hard to ensure that as much care as possible could continue to be delivered during the pandemic. Many primary care practices adapted quickly, for example, by moving to telephone or video conference appointments. While these could be challenging, such innovations also made access easier in some contexts, for example for people who faced long travel times to get to a doctor’s office. Healthcare providers adapted to using new channels of communication such as social media to provide information to their patients.

Innovation was also evident in the way the vaccination workforce was expanded. The category of health professionals who could administer vaccines was expanded to include non-regulated healthcare professionals such as healthcare assistants, with training provided. Qualified health professionals with inactive practising certificates were also encouraged to come back to the workforce to support several COVID-19 initiatives.

COVID-19 also provided the catalyst for some changes that had long been needed but not quite made it over the line, such as the introduction of e-prescriptions. Many similar adaptations introduced during the pandemic have continued to be used by healthcare services to provide extra flexibility for their patients.

Healthcare providers adapted to using new channels of communication such as social media to provide information to their patients.

xx These changes increased central governance of publicly-funded hospital and specialist services by replacing 20 district health boards with a new Crown entity, Health New Zealand. A new Māori Health authority, Te Aka Whai Ora, was established to monitor the state of Māori health and commission services.

xxi Because the risk of dying from COVID-19 is much higher for older people, the death rate per head of population was much higher for countries with older age structures – as is typically the case in high income countries (such as those in the OECD). Globally, mortality per head of population was lowest for low-income countries (including much of sub-Saharan Africa), and somewhat lower in many middle-income countries.

xxii In this context, excess mortality is the cumulative difference between the reported number of deaths since 1 January 2020 and the projected number of deaths for the same period based on previous years.

xxiii For the 2020–2022 period, the relative risk of hospitalisation from COVID-19 was 1.85 for Māori and 2.71 for Pacific peoples compared with other ethnicities (predominantly Pākeha/NZ European), while the relative risk of death was 1.91 for Māori and 2.22 for Pacific peoples. Rates are age-adjusted to the WHO world population.

xxiv In the 1918 influenza pandemic, Māori were seven times more likely to die than European New Zealanders of the same age, while in the 1957 pandemic they were six times more likely to die compared with European New Zealanders. Even in the relatively mild 2009 influenza (H1N1) pandemic, Māori had 150 percent higher mortality than European New Zealanders, while Pacific people had more than four times the risk of dying.

xxv While the country comparisons in the report cited in endnote 94 include different forms of long term care, the 75 percent estimate for Australia is specific to aged residential care, https://www.health.gov.au/resources/collections/covid-19-outbreaks-in-australian-residential-aged-care-facilities-2021

xxvi Though in the case of cancer care, service provision was largely maintained through a range of efforts – see the spotlight on cancer care during the pandemic in section 5.5.3.

xxvii The Inquiry sought evidence on what processes the Ministry of Health had for monitoring the impact of COVID-19 on health care disruption, for reviewing guidelines in response to such information, and on what measures were taken to support the health system in recovering from the disruption resulting from the COVID-19 response. The Ministry had not provided this information at the time of writing.