2.5 What happened: public information and communication I aha: ngā mōhiohio tūmatanui me te tuku whakamōhio

Clear, effective, and accurate public information and communication were crucial to Aotearoa New Zealand’s experience of the COVID-19 pandemic and the effectiveness of the response. Here we discuss how critical information was conveyed to the public – largely a success story in the early stages, but with challenges as the response progressed over time.

2.5.1 Unite Against COVID-19

It was recognised early on that the success of the response broadly rested on whether the New Zealand public – the ‘team of five million’xiii – would support the unprecedented health measures being introduced to help manage the threat from COVID-19. It was well understood by both ministers and officials that the quality of public communications would be a critical factor in the success of the response.

The new All-of-Government National Public Information Management Team established in March 2020 within the National Crisis Management Centre (see section 2.3.2) engaged an external agency, Clemenger BBDO, to support the development and delivery of the ‘Unite Against COVID-19’ campaign.

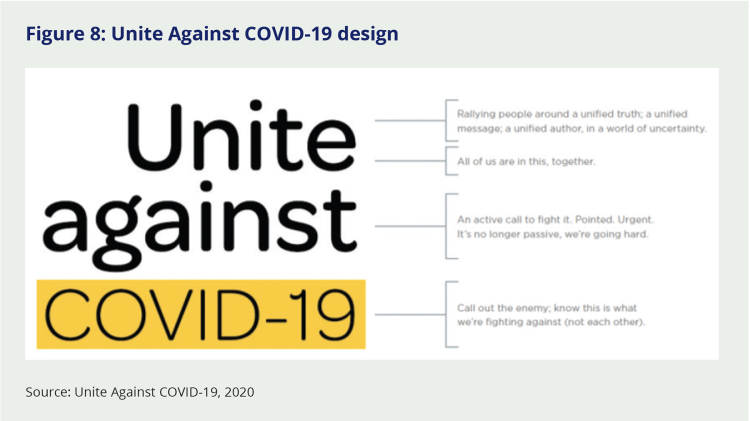

Launched on 18 March 2020, just five days after it was commissioned, the campaign was designed to be a rallying call to collective action. It aimed to get the whole country to identify as ‘on the team’ and to follow the ‘game plan’.82 Importantly, the ‘Unite’ concept also promoted social cohesion, which would be critical for a collective crisis response. The branding was deliberately designed with a focus on empathy, recognising a well-established principle of crisis communications that ‘sustained compliance in a crisis relied on not overwhelming people and minimising the sense of hopelessness’.

The campaign’s key messages were simple and actionable, and the fonts, colours, and design elements were chosen purposefully to be reassuring, and to avoid alarming or excessively medicalised messages (a striking contrast to the messaging in some jurisdictions, such as ‘It’s up to you how many people live or die’, used in Oregon in the United States).83 The simple design also knowingly made it easy for other agencies, and even community organisations, to produce their own tailored material aligned with the campaign.

The graphic below84 (Figure 8) illustrates how these elements were incorporated into the final design.

Figure 8: Unite Against COVID-19 design

Source: Unite Against COVID-19, 2020

The Unite against COVID-19 public information campaign was quickly established as an effective brand achieving high levels of recognition.85 It later received multiple awards for design and communication.

2.5.2 Digital channels

In addition to traditional channels such as press, television and radio, digital tools were launched. The www.covid19.govt.nz website was intended to be a key source of information for New Zealanders about the pandemic and the Government’s response. The new website attracted more than 800,000 visitors within a few days of launch. It was seen as a trusted source of information, especially in the first year of the pandemic.

Social media was also a crucial plank of the communications response. Regular campaign updates were posted to official ‘Unite Against COVID-19’ accounts via Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and YouTube. In these public forums, thousands of questions received direct responses from the teams handling public information and communications. These comments were also used to identify any common themes that could then inform the key messages developed for the daily 1pm press briefings that became a key feature of the response.

2.5.3 The 1pm daily briefings

From early in the pandemic,xiv ministers and senior officials held daily 1pm briefings about case numbers, alert levels, and current settings. The Ministry of Health was responsible for the briefings, which were usually conducted by the Prime Minister and the Director-General of Health.xv

Journalists attending the 1pm briefings could ask questions of the speakers at the end of their prepared remarks. The briefings were also live-streamed by multiple media outlets and quickly became routine viewing for many New Zealanders. Stakeholders explained the rationale behind the briefings in the following terms:

“The decision to concentrate the release of key information to one or two consistent times each day (updates were also provided at 6pm during key phases of the pandemic) was a deliberate decision to create a degree of certainty for people that is best practice in disaster response.”

The success of the format saw ‘the 1pm’ become an important tool for conveying accurate information, mobilising community support for Government measures and generating public trust and confidence in the response. The daily briefings remain a memorable feature of the pandemic experience.

Not surprisingly, the former Director-General told the Inquiry that the 1pm briefings ‘took up a large part of my day’. He felt this was appropriate given their importance as a communication tool that was proving very effective for establishing public trust, ensuring compliance with public health measures and ultimately stopping the spread of the disease.

Other ministers and senior officials sometimes presented the briefings, but the public came to expect to see the Prime Minister at the briefings; there would often be calls for her return if she missed one.

Former press secretaries told us that, in their view, the combination of the Prime Minister’s corralling of public sentiment to promote unity with the Director-General’s factual information made the 1pm briefings work as a public communications tool, with flow-on effects for the early success of the elimination strategy.

Daily briefings were the most praised aspect of the communications response in the public submissions to the Inquiry and were frequently characterised as informative and reassuring. Submitters often mentioned the former Director-General of Health Ashley Bloomfield and former Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern by name, praising their calm and collected communication style. Reinforcing the psychological advice that informed the briefings, submitters commended their regularity, both as a reliable source of information and for providing context to the pandemic as it evolved.

“In my honest opinion, the thing that anchored us was the constant flow of updates. The lunchtime press conferences put us at the centre of a shared task of staying home and ending this as soon as possible – hearing from not just politicians, but experts in the public health sphere.”

2.5.4 Reaching multiple communities

Key public health information was translated into a wide range of languages and formats to help different communities understand what was being asked of them during the response. For example, a physical copy of ‘Our plan – the four Alert Levels; Your plan – for staying at home’ was delivered to letterboxes nationwide. It was translated into 16 languages online, and a New Zealand Sign Language version was available. By mid-2022 Unite Against COVID-19 content was available in 27 languagesxvi and five alternative formats.

Many community organisations worked to ensure the provision of accurate, timely information to their members. We heard that an ‘alliance’ of community organisations and ethnic community media outlets formed organically to ‘collaborate to fill the gaps’ through various activities – translating and sharing daily updates and critical information, actively dispelling misinformation, and identifying providers who could meet unmet needs.86

Many individuals and groups told the Inquiry that one of their key jobs during the response was to translate the 1pm briefing for their communities. What this involved varied according to need: it could include direct language translation, making the meaning of what was said culturally relevant and/or translating what it meant from a practical viewpoint. Some (particularly representatives of Pacific media) said that communities should have received information that was culturally appropriate and delivered by people who were significant in their own culture. Some public submitters described taking on this role in the pandemic:

“I reached out to non-English speaking Chinese migrants in my community, setting up zoom meetings to teach them painting in order to help them with their isolation and ensure that they were adequately informed as they didn’t seem to be getting sufficient information in Mandarin and Cantonese.”

xiii The precise origin of the ‘team of five million’ is unclear. On the first day of Alert Level 4 lockdown, 24 March 2020, the front page of the New Zealand Herald used the term ‘Whānau of 5 million’. The Prime Minister and others began using the phrase ‘Team of five million’ soon afterwards.

xiv The first briefing (although not yet a daily occurrence), was held on 27 January 2020, fronted by the Director-General of Health Dr Ashley Bloomfield, and Director of Public Health Dr Caroline McElnay. The first briefing fronted by the Prime Minister was on 14 March 2020.

xv This phenomenon – and the unprecedented exposure it attracted for the Prime Minister and Director- General – was not unique to New Zealand. A similar ‘duo’ approach, in which a senior politician and a senior official jointly fronted regular briefings, was used in other jurisdictions including Australia, Canada, the United Kingdom and the United States. The former Director-General told us he did not see the role he played in the briefings as unusual in this regard.

xvi These languages were: Te Reo Māori, Arabic, Chinese (Simplified), Chinese (Traditional), Cook Islands Māori, Farsi, Fijian, French, Gujarati, Hindi, Japanese, Kiribati, Korean, Niuean, Punjabi, Rotuman, Samoan, Somali, Spanish, Tagalog, Tamil, Thai, Tokelauan, Tongan, Tuvaluan, Urdu, Vietnamese. Alternative formats included: New Zealand Sign Language, easy read, large print, audio and braille. Video content with audio description was also available.