2.3 What happened: governance and decision making structures I aha: ngā hanga mana whakahaere me te whakatau tikanga

The preceding overview of the country’s pre-COVID-19 pandemic preparedness and emergency management arrangements indicates the base from which the Government’s COVID-19 response began.

It was a mix of positives and negatives. The country had well-established systems for managing both emergencies and risk, which theoretically covered national pandemics; in practice, however, they were mostly geared towards regional natural disasters. Some sound legislation and governance structures were in place, along with a dedicated public service workforce. But, as happened in most other countries, many of these preparations and pre-existing arrangements proved insufficient to meet the scale and duration of a pandemic that required an unprecedented all-of-government response.

While some of the mechanisms needed to deliver a response of this kind were established quickly, many evolved over the course of the pandemic. In this section, we focus on the evolution of governance and decision-making structures.

In the first year of the pandemic, three broad approaches to organising the all-of-government response were tried. The first involved the standard ‘lead agency plus ODESC oversight’ model. Then came a bespoke approach, marked by the establishment of ‘the Quin’ (discussed further in section 2.3.2 below). It was followed by an approach designed to support a longer-term response, through a COVID-19 Group established within the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet. Originally an informal arrangement, by the end of 2020 this group had been formalised and its mandate expanded. We describe each of these in turn: our assessment of their utility and effectiveness is set out in section 2.6.

The country had well-established systems for managing emergencies, but they were mostly geared towards regional natural disasters.

2.3.1 Government initially adopted the standard ‘lead agency plus ODESC’ model

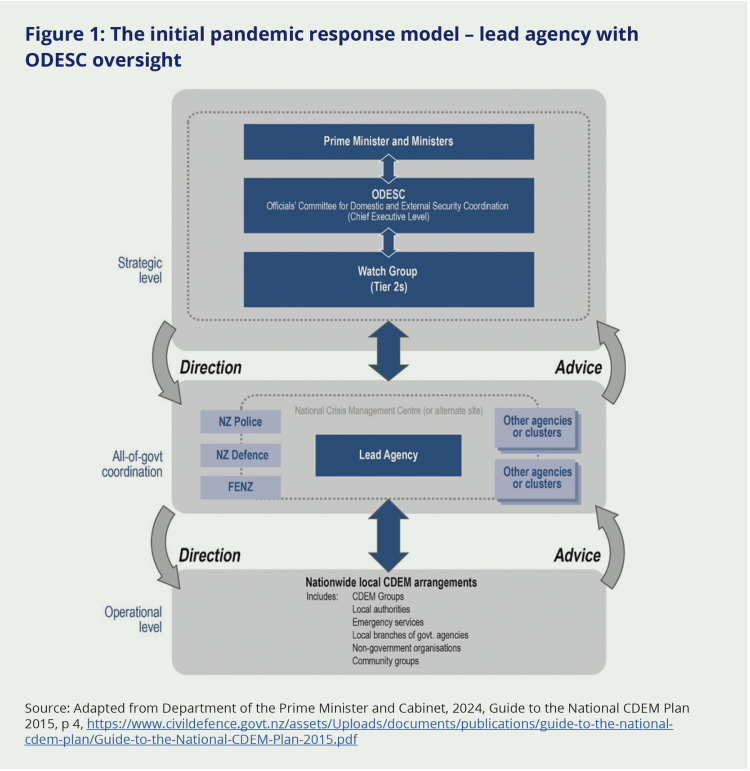

The lead agency model, with ODESC providing oversight, swung into action in January 2020 when the chair of ODESC was briefed on system readiness and risks for managing a potential pandemic. The first Watch Groupv meeting was held on 27 January 2020 and the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet activated the crisis response arrangements the same day. ODESC met for the first time on 31 January 2020 to help coordinate a cross-agency response. At this point, the pandemic response was organised in the same way as all-of-government responses to other national emergencies:

Figure 1: The initial pandemic response model – lead agency with ODESC oversight

Source: Adapted from Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, 2024, Guide to the National CDEM Plan 2015, p 4, https://www.civildefence.govt.nz/assets/Uploads/documents/publications/guide-to-the-national-cdem-plan/Guide-to-the-National-CDEM-Plan-2015.pdf

Under this model, the Ministry of Health – identified in the National Civil Defence Emergency Management Plan 2015 as the lead agency for emergencies arising from infectious human diseases – had the ‘primary mandate’ for managing the COVID-19 response, although it was not expected to work alone. The Ministry’s responsibilities included monitoring and assessing the situation, planning for and coordinating the national response, reporting to ODESC and providing policy advice, and coordinating the dissemination of public information.36

Meanwhile, ODESC provides the Prime Minister and Cabinet with advice on priorities and mitigation of risks beyond the lead agency’s control, and exercises policy oversight. ODESC also helps ensure the lead agency and those supporting it had the resources and capabilities required for an effective response.

This model was quickly deemed by officials at the time as unsuited for responding to the scale of the evolving pandemic. There were several reasons. At the core of the ODESC model is a group of chief executives who work as a collective, not a functioning governance arrangement for delivering the strategic advice and decisions needed for the response over time. ODESC did not have the systems and resources to oversee a crisis as all-encompassing as COVID-19, and outside of ODESC, there was no all-of-government structure that could step in if the lead agency model was not appropriate.vi This was the case with the COVID-19 response, which was far more wide-reaching than a single agency could be expected to manage. This meant that, in the early days, the Ministry of Health was trying to fulfil multiple functions – including leading the health system response and associated technical aspects, leading other critical elements of the response such as managed isolation and quarantine (MIQ), providing strategic advice to ministers, and trying to coordinate activities across government.

As one stakeholder told us, ‘An everything crisis requires an everything response’ – a sentiment we heard from many senior response officials. Accordingly, an alternative all-of-government model was introduced in March 202037 and remained in place until the end of June 2020.

2.3.2 A bespoke all-of-government approach was developed

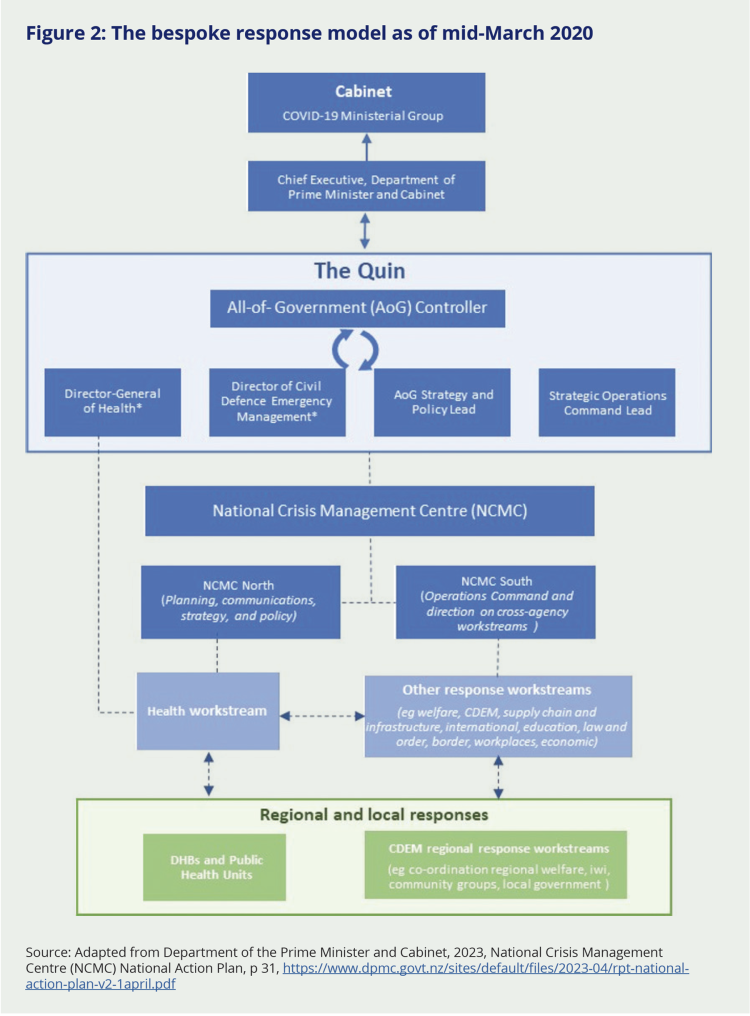

An early indicator of a shift in approach came after the Chair of ODESC directed the National Crisis Management Centre to be activated on 6 March 2020. The ODESC Chair created a new position on 11 March 2020, the All-of-Government Controller, to oversee the all-of-government response.vii Leadership and governance structures were also modified, including the establishment of a new leadership body, the Quin. It comprised the All-of-Government Controller (John Ombler, as Chair) and four key response leaders: Dr Ashley Bloomfield, the Director-General of Health; Sarah Stuart-Black, the Director of Civil Defence Emergency Management; Mike Bush, head of the Strategic Operations Command Centreviii whose role included overseeing and providing direction to cross-agency activities; and Dr Peter Crabtree, the All-of-Government Strategy and Policy Lead.38

An all-of-government communications function was also created early in the response. In a standard emergency response, the lead agency (in this case the Ministry of Health) is responsible for the provision of public information. However, it quickly became apparent that the public communications task was going to be more significant than the Ministry of Health could manage alone. In February 2020, ODESC members agreed there was a need for ‘more aggressive and direct communications’ about COVID-19 and the Chair of ODESC commissioned a review of the Ministry of Health’s capacity to deliver the necessary communications functions. This led to the creation of a new All-of-Government National Public Information Management Team within the National Crisis Management Centre, thereby shifting primary responsibility for public communications from the Ministry of Health to the all-of-government crisis management centre.

Alongside these new arrangements – and in another sign of the need for bespoke solutions to support the COVID-19 pandemic response – new legislation was also being developed, including the COVID-19 Public Health Response Bill. When enacted, it would become the lynchpin of the pandemic response, replacing the Health Act 1956 as the primary legal basis for the Government’s use of mandatory public health measures.ix The Bill’s Explanatory Note indicated the Government’s rationale for its development: it provided a ‘fit-for-purpose legal framework for managing the unprecedented circumstances of the COVID-19 epidemic in a coordinated and orderly way, even if there is no longer a national state of emergency’. It would also establish ‘decision-making processes that are more modern and consistent with recommended practice by legal academics and others’.39

By mid-March 2020, the structure of the all-of-government response looked very different from the arrangements in place only two months earlier:

Figure 2: The bespoke response model as of mid-March 2020

Source: Adapted from Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, 2023, National Crisis Management Centre (NCMC) National Action Plan, p 31, https://www.dpmc.govt.nz/sites/default/files/2023-04/rpt-national-action-plan-v2-1april.pdf

2.3.3 The model was refined over time

Rapid reviews of the model were carried out in April40 and October of 202041 to check if it was providing the leadership and coordination necessary for the response.x

The aim of the first review, commissioned by the chair of ODESC not long after the introduction of the Quin in mid-March 2020, was to identify what arrangements would best support the all-of-government response into the future. Recognising that ‘what got the country through the first phase [of the pandemic] would not be sustainable or fit for purpose in the medium term’, the review called for ‘a refreshed mandate and simplification of existing structures and accountabilities’42 going forward.xi

Thus, when the National Crisis Management Centre was deactivated on 30 June 2020, many of its functions transferred to a newly-established COVID-19 All-of-Government Response Group within the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet. The Group’s leadership team effectively replaced elements of the Quin from this point on (noting that the Director-General of Health and the Director of Civil Defence Emergency Management retained their statutory roles, and the Ministry of Health was still the lead agency). As at December 2020, over 80 percent of the staff in the All-of-Government Response Group were seconded from other agencies across the public service.43

The Group was charged with developing ‘a more forward-looking work programme’. It had four key areas of responsibility: providing Cabinet with strategy and policy advice; operational coordination; data analytics, monitoring, reporting and insights; and public communications.44 To avoid duplication of effort, it was to undertake only work that other agencies could not do, and some response activities that had been led centrally – such as the managed isolation and quarantine (MIQ) system – were transferred to relevant agencies (in this case, to the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment).45

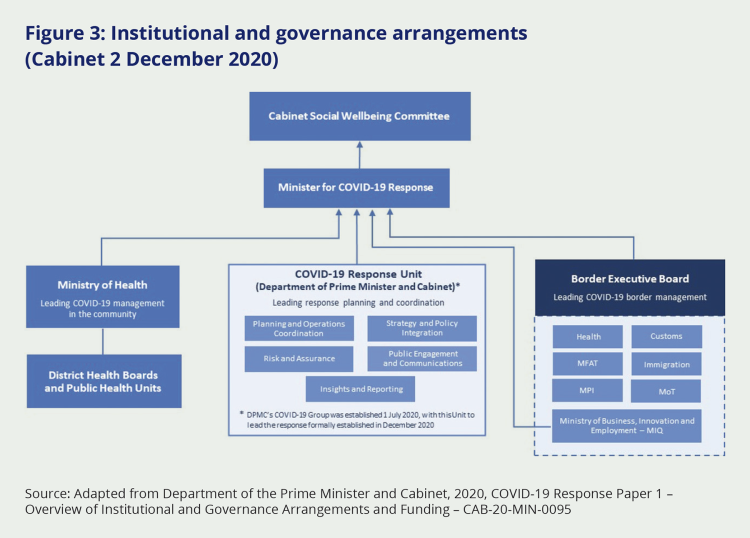

The second rapid review of the all-of-government response released in October 2020 recommended ‘declutter[ing] the governance landscape’.46 This led to the establishment of a COVID-19 Chief Executives Board on 17 November 2020. It comprised 12 departmental chief executives,xii who were expected to reflect the views of their sectors and stakeholders (which included iwi, the private sector, non-governmental organisations, and vulnerable communities). The Board’s role was to ensure that ‘the system is informed, is doing what it needs to, at the pace required, and that risks are identified and mitigated.’47 It met for the first time in mid-November 2020.

The first year of the pandemic ended with Cabinet approving a recalibrated COVID-19 response system (shown below) and confirming funding for it until the end of June 2022. The new arrangements also recognised that a single agency could not manage the full response alone, and multiple lines of accountability were required. The role of the COVID-19 Group in the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet was enhanced, and it was now mandated to provide strategic leadership and central coordination of the all-of-government response. The entire system became accountable to the Minister for COVID-19 Response, a position created in November 2020.

Figure 3: Institutional and governance arrangements (Cabinet 2 December 2020)

Source: Adapted from Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, 2020, COVID-19 Response Paper 1 – Overview of Institutional and Governance Arrangements and Funding – CAB-20-MIN-0095

v Under the ODESC system, Watch Groups comprising senior officials from relevant agencies are established to monitor potential, developing or actual crises. See Appendix A.

vi For example, in situations where the lead agency lacked the capacity or capability to coordinate the response, the response required actions that exceeded what a lead agency could reasonably coordinate, or if the crisis was likely to require a prolonged response.

vii Former Deputy State Services Commissioner John Ombler was appointed the All-of-Government Controller and held the role until late October 2020; he was at the same time Deputy Chief Executive of the All-of-Government Response Group in the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet.

viii Mike Bush was still the Commissioner of Police when he took up this role and held both roles until 2 April 2020 when his term as Commissioner finished.

ix The Act came into effect just a day after the Bill was introduced to Parliament.

x In line with our terms of reference, we have not sought to replicate the work of these reviews (nor that of the Office of the Auditor-General into the all-of-government coordination in the first year of the response). Rather, we have used their findings, alongside our own evidence, to inform this analysis and our subsequent lessons.

xi The Auditor-General also noted that the new arrangements put in place during 2020 (in particular the Quin) posed challenges for those working in the system. These included strained relationships between the National Crisis Management Centre and the Ministry of Health.

xii Board members were from the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, New Zealand Customs Service, Ministry of Justice, Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade, Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment, the Treasury, Ministry of Social Development, Te Puni Kōkiri, Ministry of Transport, Ministry of Health. The heads of the Crown Law Office, Te Kawa Mataaho and the COVID-19 Group were ‘additional members’.